History of Earth

[1][2] Nearly all branches of natural science have contributed to understanding of the main events of Earth's past, characterized by constant geological change and biological evolution.

The Hadean eon represents the time before a reliable (fossil) record of life; it began with the formation of the planet and ended 4.0 billion years ago.

The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates at least from 3.5 billion years ago,[7][8][9] during the Eoarchean Era, after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean eon.

This sudden diversification of life forms produced most of the major phyla known today, and divided the Proterozoic Eon from the Cambrian Period of the Paleozoic Era.

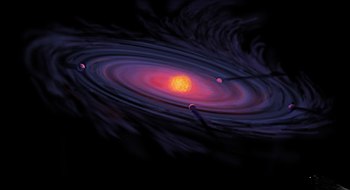

It was composed of hydrogen and helium created shortly after the Big Bang 13.8 Ga (billion years ago) and heavier elements ejected by supernovae.

Small perturbations due to collisions and the angular momentum of other large debris created the means by which kilometer-sized protoplanets began to form, orbiting the nebular center.

Meanwhile, in the outer part of the nebula gravity caused matter to condense around density perturbations and dust particles, and the rest of the protoplanetary disk began separating into rings.

[41] Nevertheless, detrital zircon crystals dated to 4.4 Ga show evidence of having undergone contact with liquid water, suggesting that the Earth already had oceans or seas at that time.

Present life forms could not have survived at Earth's surface, because the Archean atmosphere lacked oxygen hence had no ozone layer to block ultraviolet light.

[1]: 258 [57] The initial crust, which formed when the Earth's surface first solidified, totally disappeared from a combination of this fast Hadean plate tectonics and the intense impacts of the Late Heavy Bombardment.

Though most comets are today in orbits farther away from the Sun than Neptune, computer simulations show that they were originally far more common in the inner parts of the Solar System.

An experiment in 1952 by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey showed that such molecules could form in an atmosphere of water, methane, ammonia and hydrogen with the aid of sparks to mimic the effect of lightning.

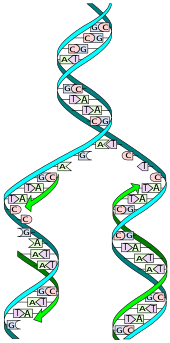

[78] Even the simplest members of the three modern domains of life use DNA to record their "recipes" and a complex array of RNA and protein molecules to "read" these instructions and use them for growth, maintenance, and self-replication.

[79] They could have formed an RNA world in which there were individuals but no species, as mutations and horizontal gene transfers would have meant that the offspring in each generation were quite likely to have different genomes from those that their parents started with.

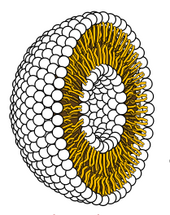

[95] Experiments that simulated the conditions of the early Earth have reported the formation of lipids, and these can spontaneously form liposomes, double-walled "bubbles", and then reproduce themselves.

Current phylogenetic evidence suggests that the last universal ancestor (LUA) lived during the early Archean eon, perhaps 3.5 Ga or earlier.

Glacial deposits found in South Africa date back to 2.2 Ga, at which time, based on paleomagnetic evidence, they must have been located near the equator.

[120] The earliest fossils possessing features typical of fungi date to the Paleoproterozoic era, some 2.4 Ga ago; these multicellular benthic organisms had filamentous structures capable of anastomosis.

Some of these lived in colonies, and gradually a division of labor began to take place; for instance, cells on the periphery might have started to assume different roles from those in the interior.

[132] Reconstructions of tectonic plate movement in the past 250 million years (the Cenozoic and Mesozoic eras) can be made reliably using fitting of continental margins, ocean floor magnetic anomalies and paleomagnetic poles.

Paleomagnetic poles are supplemented by geologic evidence such as orogenic belts, which mark the edges of ancient plates, and past distributions of flora and fauna.

The existence of Pannotia depends on the timing of the rifting between Gondwana (which included most of the landmass now in the Southern Hemisphere, as well as the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent) and Laurentia (roughly equivalent to current-day North America).

[citation needed] Early Paleozoic climates were warmer than today, but the end of the Ordovician saw a short ice age during which glaciers covered the south pole, where the huge continent Gondwana was situated.

[158] The diversity of life forms did not increase significantly because of a series of mass extinctions that define widespread biostratigraphic units called biomeres.

[161]: 34 Oxygen accumulation from photosynthesis resulted in the formation of an ozone layer that absorbed much of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation, meaning unicellular organisms that reached land were less likely to die, and prokaryotes began to multiply and become better adapted to survival out of the water.

The timing of the first animals to leave the oceans is not precisely known: the oldest clear evidence is of arthropods on land around 450 Ma,[169] perhaps thriving and becoming better adapted due to the vast food source provided by the terrestrial plants.

[187] This all changed during the mid to late Eocene when the circum-Antarctic current formed between Antarctica and Australia which disrupted weather patterns on a global scale.

[citation needed] Three million years ago saw the start of the Pleistocene epoch, which featured dramatic climatic changes due to the ice ages.

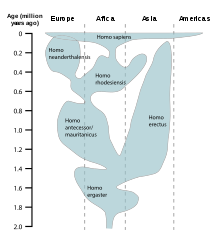

[197]: 17–19 By 11,000 years ago, Homo sapiens had reached the southern tip of South America, the last of the uninhabited continents (except for Antarctica, which remained undiscovered until 1820 AD).

The invention of writing enabled complex societies to arise: record-keeping and libraries served as a storehouse of knowledge and increased the cultural transmission of information.