History of molecular theory

In chemistry, the history of molecular theory traces the origins of the concept or idea of the existence of strong chemical bonds between two or more atoms.

The modern concept of molecules can be traced back towards pre-scientific and Greek philosophers such as Leucippus and Democritus who argued that all the universe is composed of atoms and voids.

Moreover, connections were explained by material links in which single atoms were supplied with attachments: some with hooks and eyes others with balls and sockets (see diagram).

Among other scientists of that time Gassendi deeply studied ancient history, wrote major works about Epicurus natural philosophy and was a persuasive propagandist of it.

Boyle argued that matter's basic elements consisted of various sorts and sizes of particles, called "corpuscles", which were capable of arranging themselves into groups.

In 1680, using the corpuscular theory as a basis, French chemist Nicolas Lemery stipulated that the acidity of any substance consisted in its pointed particles, while alkalis were endowed with pores of various sizes.

These were lists, prepared by collating observations on the actions of substances one upon another, showing the varying degrees of affinity exhibited by analogous bodies for different reagents.

In this work, Bernoulli positioned the argument, still used to this day, that gases consist of great numbers of molecules moving in all directions, that their impact on a surface causes the gas pressure that we feel, and that what we experience as heat is simply the kinetic energy of their motion.

The theory was not immediately accepted, in part because conservation of energy had not yet been established, and it was not obvious to physicists how the collisions between molecules could be perfectly elastic.

In 1789, William Higgins published views on what he called combinations of "ultimate" particles, which foreshadowed the concept of valency bonds.

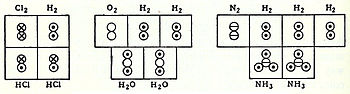

[8] His 1811 paper "Essay on Determining the Relative Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies", he essentially states, i.e. according to Partington's A Short History of Chemistry, that:[9] The smallest particles of gases are not necessarily simple atoms, but are made up of a certain number of these atoms united by attraction to form a single molecule.Note that this quote is not a literal translation.

Avogadro developed this hypothesis to reconcile Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac's 1808 law on volumes and combining gases with Dalton's 1803 atomic theory.

[11] One month after Kekulé's second paper appeared, Couper's independent and largely identical theory of molecular structure was published.

[12] In later publications, Couper's bonds were represented using straight dotted lines (although it is not known if this is the typesetter's preference) such as with alcohol and oxalic acid below: In 1861, an unknown Vienna high-school teacher named Joseph Loschmidt published, at his own expense, a booklet entitled Chemische Studien I, containing pioneering molecular images which showed both "ringed" structures as well as double-bonded structures, such as:[13] Loschmidt also suggested a possible formula for benzene, but left the issue open.

Benzene presents a special problem in that, to account for all the bonds, there must be alternating double carbon bonds: In 1865, German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann was the first to make stick-and-ball molecular models, which he used in lecture at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, such as methane shown below: The basis of this model followed the earlier 1855 suggestion by his colleague William Odling that carbon is tetravalent.

Hofmann's color scheme, to note, is still used to this day: carbon = black, nitrogen = blue, oxygen = red, chlorine = green, sulfur = yellow, hydrogen = white.

In this year, the renowned Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell published his famous thirteen page article 'Molecules' in the September issue of Nature.

We are told that an 'atom' is a material point, invested and surrounded by 'potential forces' and that when 'flying molecules' strike against a solid body in constant succession it causes what is called pressure of air and other gases.

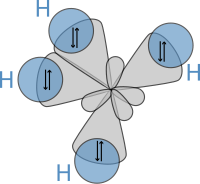

In 1874, Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Achille Le Bel independently proposed that the phenomenon of optical activity could be explained by assuming that the chemical bonds between carbon atoms and their neighbors were directed towards the corners of a regular tetrahedron.

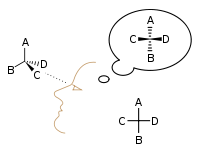

Emil Fischer developed the Fischer projection technique for viewing 3-D molecules on a 2-D sheet of paper: In 1898, Ludwig Boltzmann, in his Lectures on Gas Theory, used the theory of valence to explain the phenomenon of gas phase molecular dissociation, and in doing so drew one of the first rudimentary yet detailed atomic orbital overlap drawings.

We thus have a concrete picture of that physical entity, that "hook and eye" which is part of the creed of the organic chemist.The following year, in 1917, an unknown American undergraduate chemical engineer named Linus Pauling was learning the Dalton hook-and-eye bonding method at the Oregon Agricultural College, which was the vogue description of bonds between atoms at the time.

The four bonds are of the same length and strength, which yields a molecular structure as shown below: Owing to these exceptional theories, Pauling won the 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

In 1926, French physicist Jean Perrin received the Nobel Prize in physics for proving, conclusively, the existence of molecules.

First, he used a gamboge soap-like emulsion, second by doing experimental work on Brownian motion, and third by confirming Einstein's theory of particle rotation in the liquid phase.

This work verified for the first time that crystal molecules are actually linked or stacked merged tear drop constructions.