Homology (biology)

Evolutionary biology explains homologous structures as retained heredity from a common ancestor after having been subjected to adaptive modifications for different purposes as the result of natural selection.

Homology was later explained by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution in 1859, but had been observed before this from Aristotle's biology onwards, and it was explicitly analysed by Pierre Belon in 1555.

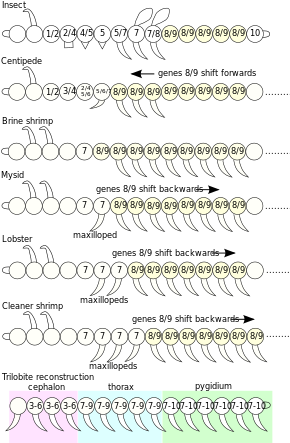

In developmental biology, organs that developed in the embryo in the same manner and from similar origins, such as from matching primordia in successive segments of the same animal, are serially homologous.

Examples include the legs of a centipede, the maxillary and labial palps of an insect, and the spinous processes of successive vertebrae in a vertebrate's backbone.

Male and female reproductive organs are homologous if they develop from the same embryonic tissue, as do the ovaries and testicles of mammals, including humans.

The pattern of similarity was interpreted as part of the static great chain of being through the mediaeval and early modern periods: it was not then seen as implying evolutionary change.

[2][3] In 1790, Goethe stated his foliar theory in his essay "Metamorphosis of Plants", showing that flower parts are derived from leaves.

[5] When Geoffroy went further and sought homologies between Georges Cuvier's embranchements, such as vertebrates and molluscs, his claims triggered the 1830 Cuvier-Geoffroy debate.

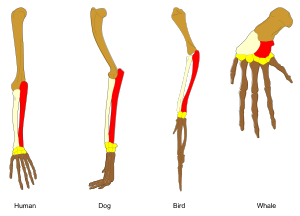

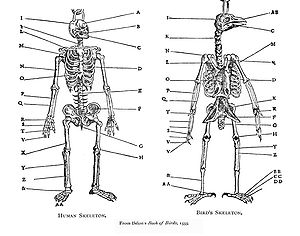

[3] The term "homology" was first used in biology by the anatomist Richard Owen in 1843 when studying the similarities of vertebrate fins and limbs, defining it as the "same organ in different animals under every variety of form and function",[6] and contrasting it with the matching term "analogy" which he used to describe different structures with the same function.

In 1859, Charles Darwin explained homologous structures as meaning that the organisms concerned shared a body plan from a common ancestor, and that taxa were branches of a single tree of life.

[2][7][3] The word homology, coined in about 1656, is derived from the Greek ὁμόλογος homologos from ὁμός homos 'same' and λόγος logos 'relation'.

The same major forearm bones (humerus, radius, and ulna[c]) are found in fossils of lobe-finned fish such as Eusthenopteron.

For example, the wings of insects and birds evolved independently in widely separated groups, and converged functionally to support powered flight, so they are analogous.

For example, in an aligned DNA sequence matrix, all of the A, G, C, T or implied gaps at a given nucleotide site are homologous in this way.

[20][21] As implied in this definition, many cladists consider secondary homology to be synonymous with synapomorphy, a shared derived character or trait state that distinguishes a clade from other organisms.

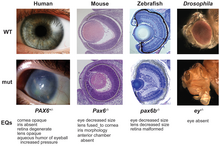

For example, deep homologies like the pax6 genes that control the development of the eyes of vertebrates and arthropods were unexpected, as the organs are anatomically dissimilar and appeared to have evolved entirely independently.

The malleus and incus develop in the embryo from structures that form jaw bones (the quadrate and the articular) in lizards, and in fossils of lizard-like ancestors of mammals.

In many plants, defensive or storage structures are made by modifications of the development of primary leaves, stems, and roots.

[36][37] The four types of flower parts, namely carpels, stamens, petals, and sepals, are homologous with and derived from leaves, as Goethe correctly noted in 1790.

Each of the four types of flower parts is serially repeated in concentric whorls, controlled by a small number of genes acting in various combinations.