Hour

An hour (symbol: h;[1] also abbreviated hr) is a unit of time historically reckoned as 1⁄24 of a day and defined contemporarily as exactly 3,600 seconds (SI).

In the modern metric system, hours are an accepted unit of time defined as 3,600 atomic seconds.

[5] The Anglo-Norman term was a borrowing of Old French ure, a variant of ore, which derived from Latin hōra and Greek hṓrā (ὥρα).

Like Old English tīd and stund, hṓrā was originally a vaguer word for any span of time, including seasons and years.

It was accompanied by the rise of Sirius before the sunrise, and the appearance of 12 constellations across the night sky, to which the Egyptians assigned some significance.

[13] The Greek astronomer Andronicus of Cyrrhus oversaw the construction of a horologion called the Tower of the Winds in Athens during the first century BCE.

By AD 60, the Didache recommends disciples to pray the Lord's Prayer three times a day; this practice found its way into the canonical hours as well.

The word "Vigils", at first applied to the Night Office, comes from a Latin source, namely the Vigiliae or nocturnal watches or guards of the soldiers.

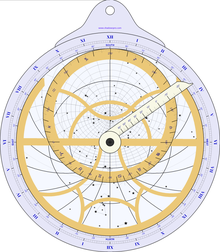

[16] The first and twelfth of the Horae were added to the original set of ten: Medieval astronomers such as al-Biruni[18] and Sacrobosco,[19] divided the hour into 60 minutes, each of 60 seconds; this derives from Babylonian astronomy, where the corresponding terms[clarification needed] denoted the time required for the Sun's apparent motion through the ecliptic to describe one minute or second of arc, respectively.

In spite of this, a few localities continued to use decimal time for six years for civil status records, until 1800, after Napoleon's Coup of 18 Brumaire.

The metric system bases its measurements of time upon the second, defined since 1952 in terms of the Earth's rotation in AD 1900.

In modern life, the ubiquity of clocks and other timekeeping devices means that segmentation of days according to their hours is commonplace.

Most forms of employment, whether wage or salaried labour, involve compensation based upon measured or expected hours worked.

However, with accurate clocks and modern astronomical equipment (and the telegraph or similar means to transfer a time signal in a split-second), this issue is much less relevant.

[25] They are so named from the false belief of ancient authors that the Babylonians divided the day into 24 parts, beginning at sunrise.

[24] This is also the system used in Jewish law and frequently called "Talmudic hour" (Sha'a Zemanit) in a variety of texts.

This manner of counting hours had the advantage that everyone could easily know how much time they had to finish their day's work without artificial light.

[28] For many centuries, up to 1925, astronomers counted the hours and days from noon, because it was the easiest solar event to measure accurately.

The ancient Egyptians began dividing the night into wnwt at some time before the compilation of the Dynasty V Pyramid Texts[29] in the 24th century BC.

The coffin diagrams show that the Egyptians took note of the heliacal risings of 36 stars or constellations (now known as "decans"), one for each of the ten-day "weeks" of their civil calendar.

(Another seven stars were noted by the Egyptians during the twilight and predawn periods,[citation needed] although they were not important for the hour divisions.)

These were filled to the brim at sunset and the hour determined by comparing the water level against one of its 12 gauges, one for each month of the year.

The morning and evening periods when the sundials failed to note time were observed as the first and last hours.

By the New Kingdom, each hour was conceived as a specific region of the sky or underworld through which Ra's solar barge travelled.

[36] As the protectors and resurrectors of the sun, the goddesses of the night hours were considered to hold power over all lifespans[36] and thus became part of Egyptian funerary rituals.

[48] The system is said to have been used since remote antiquity,[48] credited to the legendary Yellow Emperor,[49] but is first attested in Han-era water clocks[50] and in the 2nd-century history of that dynasty.

[45][53] Imperial China continued to use ke and geng but also began to divide the day into 12 "double hours" (t 時, s 时, oc *də,[47] p shí, lit.

[54] The first shi originally ran from 11 pm to 1 am but was reckoned as starting at midnight by the time of the History of Song, compiled during the early Yuan.

As with the Egyptian night and daytime hours, the division of the day into 12 shi has been credited to the example set by the rough number of lunar cycles in a solar year,[56] although the 12-year Jovian orbital cycle was more important to traditional Chinese[57] and Babylonian reckoning of the zodiac.

[61] The Vedas and Puranas employed units of time based on the sidereal day (nakṣatra ahorātra).