Human brain

[43][44] Mast cells serve the same general functions in the body and central nervous system, such as effecting or regulating allergic responses, innate and adaptive immunity, autoimmunity, and inflammation.

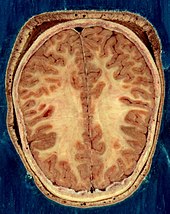

These smallest of blood vessels in the brain, are lined with cells joined by tight junctions and so fluids do not seep in or leak out to the same degree as they do in other capillaries; this creates the blood–brain barrier.

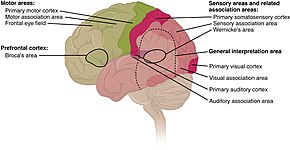

The pathway fibres travel up the spinal cord and connect with second-order neurons in the reticular formation of the brainstem for pain and temperature, and also terminate at the ventrobasal complex of the thalamus for gross touch.

Information about blood oxygen, carbon dioxide and pH levels are also sensed on the walls of arteries in the peripheral chemoreceptors of the aortic and carotid bodies.

A substantial part of current understanding of the interactions between the two hemispheres has come from the study of "split-brain patients"—people who underwent surgical transection of the corpus callosum in an attempt to reduce the severity of epileptic seizures.

[115][116] Emotions are generally defined as two-step multicomponent processes involving elicitation, followed by psychological feelings, appraisal, expression, autonomic responses, and action tendencies.

[131] In humans, blood glucose is the primary source of energy for most cells and is critical for normal function in a number of tissues, including the brain.

[148] The Human Connectome Project was a five-year study launched in 2009 to analyse the anatomical and functional connections of parts of the brain, and has provided much data.

One technique is functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) which has the advantages over earlier methods of SPECT and PET of not needing the use of radioactive materials and of offering a higher resolution.

Changes in gene expression alter the levels of proteins in various neural pathways and this has been shown to be evident in synaptic contact dysfunction or loss.

This dysfunction has been seen to affect many structures of the brain and has a marked effect on inhibitory neurons resulting in a decreased level of neurotransmission, and subsequent cognitive decline and disease.

Traumatic brain injury, for example received in contact sport, after a fall, or a traffic or work accident, can be associated with both immediate and longer-term problems.

[125][129][178] Treatment for mental disorders may include psychotherapy, psychiatry, social intervention and personal recovery work or cognitive behavioural therapy; the underlying issues and associated prognoses vary significantly between individuals.

[185][188] Most cerebral arteriovenous malformations are congenital, these tangled networks of blood vessels may remain without symptoms but at their worst may rupture and cause intracranial hemorrhaging.

[191] Most strokes result from loss of blood supply, typically because of an embolus, rupture of a fatty plaque causing thrombus, or narrowing of small arteries.

[195] A multidisciplinary team including speech pathologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and psychologists plays a large role in supporting a person affected by a stroke and their rehabilitation.

[203] Clinical observations, including a total lack of responsiveness, a known diagnosis, and neural imaging evidence, may all play a role in the decision to pronounce brain death.

Doubt about the possibility of a mechanistic explanation of thought drove René Descartes, and most other philosophers along with him, to dualism: the belief that the mind is to some degree independent of the brain.

There is clear empirical evidence that physical manipulations of, or injuries to, the brain (for example by drugs or by lesions, respectively) can affect the mind in potent and intimate ways.

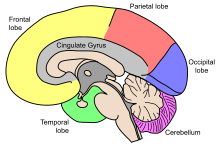

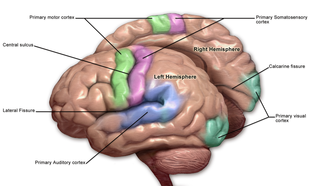

[215] The most consistent associations are observed within the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, the hippocampi, and the cerebellum, but these only account for a relatively small amount of variance in IQ, which itself has only a partial relationship to general intelligence and real-world performance.

[228] Also in the fifth century BC in Athens, the unknown author of On the Sacred Disease, a medical treatise which is part of the Hippocratic Corpus and traditionally attributed to Hippocrates, believed the brain to be the seat of intelligence.

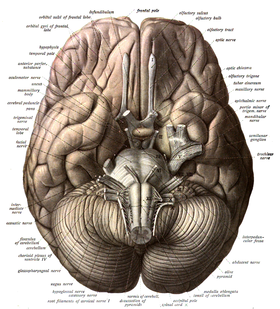

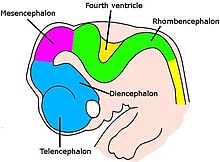

[230] Herophilus of Chalcedon in the fourth and third centuries BC distinguished the cerebrum and the cerebellum, and provided the first clear description of the ventricles; and with Erasistratus of Ceos experimented on living brains.

[228] Anatomist physician Galen in the second century AD, during the time of the Roman Empire, dissected the brains of sheep, monkeys, dogs, and pigs.

[236] Vesalius rejected the common belief that the ventricles were responsible for brain function, arguing that many animals have a similar ventricular system to humans, but no true intelligence.

He suggested that the pineal gland was where the mind interacted with the body, serving as the seat of the soul and as the connection through which animal spirits passed from the blood into the brain.

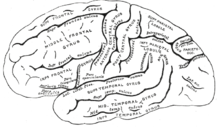

In these he described the structure of the cerebellum, the ventricles, the cerebral hemispheres, the brainstem, and the cranial nerves, studied its blood supply; and proposed functions associated with different areas of the brain.

[242] In the 1820s, Jean Pierre Flourens pioneered the experimental method of damaging specific parts of animal brains describing the effects on movement and behavior.

[246] Neuroscience during the twentieth century began to be recognised as a distinct unified academic discipline, with David Rioch, Francis O. Schmitt, and Stephen Kuffler playing critical roles in establishing the field.

[248] During the same period, Schmitt established the Neuroscience Research Program, an inter-university and international organisation, bringing together biology, medicine, psychological and behavioural sciences.

[251][252] The capacity of the brain to re-organise and change with age, and a recognised critical development period, were attributed to neuroplasticity, pioneered by Margaret Kennard, who experimented on monkeys during the 1930-40s.