Hydrothermal vent microbial communities

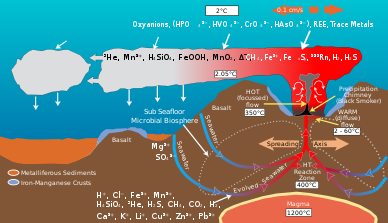

Chemolithoautotrophic bacteria derive nutrients and energy from the geological activity at Hydrothermal vents to fix carbon into organic forms.

[2] Due to the absence of sunlight at these ocean depths, energy is provided by chemosynthesis where symbiotic bacteria and archaea form the bottom of the food chain and are able to support a variety of organisms such as Riftia pachyptila and Alvinella pompejana.

These organisms use this symbiotic relationship in order to use and obtain the chemical energy that is released at these hydrothermal vent areas.

Extreme conditions in the hydrothermal vent environment mean that microbial communities that inhabit these areas need to adapt to them.

These hyperthermophilic microbes are thought to contain proteins that have extended stability at higher temperatures due to intramolecular interactions but the exact mechanisms are not clear yet.

[8] Microbial communities at hydrothermal vents mediate the transformation of energy and minerals produced by geological activity into organic material.

[15] RuBisCO has been identified in members of the microbial community such as Thiomicrospira, Beggiatoa, zetaproteobacterium, and gammaproteobacterial endosymbionts of tubeworms, bivalves, and gastropods.

[16] The Reductive Carboxylic Acid Cycle (rTCA) is the second most commonly found carbon fixation pathway at hydrothermal vents.

[17] Anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) is typically coupled to reduction of sulfate or Fe and Mn as terminal electron acceptors as these are most plentiful at hydrothermal vents.

[21] However, autotropic methanogenesis performed by many thermophilic species require H2 as an electron donor so microbial growth is limited by H2 availability.

[10] Sulfide is plentiful at Hydrothermal Vents, with concentrations from one to tens of mM, whereas the surrounding ocean water usually only contains a few nano molars.

[18] This method is favoured by organisms living in highly anoxic areas of the hydrothermal vent,[23] thus are one of the predominant processes that occur within the sediments.

[14] Species that reduce sulfate have been identified in Archaea and members of Deltaproteobacteria such as Desulfovibrio, Desulfobulbus, Desulfobacteria, and Desulfuromonas at hydrothermal vents.

They are the predominant population in the majority of hydrothermal vents because their source of energy is widely available, and chemosynthesis rates increase in aerobic conditions.

[11] Many types of methanotrophic bacteria exist, which require oxygen and fix CH4, CH3NH2, and other C1 compounds, including CO2 and CO, if present in vent water.

[11] Desulfonauticus submarinus is a hydrogenotroph that reduces sulfur-compounds in warm vents and has been found in tube worms R. pachyptila and Alvinella pompejana.

[28] These bacteria are commonly found in iron and manganese deposits on surfaces exposed intermittently to plumes of hydrothermal and bottom seawater.

[11] At warm vents, common symbionts for bacteria are deep-sea clams, Calpytogena magnifica, mussels such as Bathyomodiolus thermophilus and pogonophoran tube worms, Riftia pachyptila, and Alvinella pompejana.

These organisms have become so reliant on their symbionts that they have lost all morphological features relating to ingestion and digestion, though the bacteria are provided with H2S and free O2.

[11] Additionally, methane-oxidizing bacteria have been isolated from C. magnifica and R. pachyptila, which indicate that methane assimilation may take place within the trophosome of these organisms.

[9] To illustrate the incredible diversity of hydrothermal vents, the list below is a cumulative representation of bacterial phyla and genera, in alphabetical order.

Microbial communities inhabiting deep-sea hydrothermal vent chimneys appear to be highly enriched in genes that encode enzymes employed in DNA mismatch repair and homologous recombination.

[30] As their infections are often fatal, they constitute a significant source of mortality and thus have widespread influence on biological oceanographic processes, evolution and biogeochemical cycling within the ocean.

[33] As in other marine environments, deep-sea hydrothermal viruses affect the abundance and diversity of prokaryotes and therefore impact microbial biogeochemical cycling by lysing their hosts to replicate.

However, in contrast to their role as a source of mortality and population control, viruses have also been postulated to enhance survival of prokaryotes in extreme environments, acting as reservoirs of genetic information.

[35]Each second, "there's roughly Avogadro's number of infections going on in the ocean, and every one of those interactions can result in the transfer of genetic information between virus and host."

— Curtis Suttle[36] Temperate phages (those not causing immediate lysis) can sometimes confer phenotypes that improve fitness in prokaryotes [7] The lysogenic life-cycle can persist stably for thousands of generations of infected bacteria and the viruses can alter the host's phenotype by enabling genes (a process known as lysogenic conversion) which can therefore allow hosts to cope with different environments.

The same study's genetic analysis found that 51% of the viral metagenome sequences were unknown (lacking homology to sequenced data), with high diversity across vent environments but lower diversity for specific vent sites, which indicates high specificity for viral targets.

A study found that 15 of 18 viral genomes sequenced from samples of vent plumes contained genes closely related to an enzyme that the SUP05 chemolithoautotrophs use to extract energy from sulfur compounds.

The evidence suggests that deep-sea hydrothermal vent viral evolutionary strategies promote prolonged host integration, favoring a form of mutualism rather than classic parasitism.