Hygiene

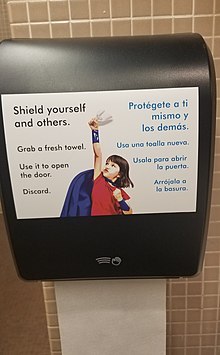

In medicine and everyday life, hygiene practices are preventive measures that reduce the incidence and spread of germs leading to disease.

[13] Sites that accumulate stagnant water – such as sinks, toilets, waste pipes, cleaning tools, and face cloths – readily support microbial growth and can become secondary reservoirs of infection, though species are mostly those that threaten "at risk" groups.

Pathogens (such as potentially infectious bacteria and viruses – colloquially called "germs") are constantly shed via mucous membranes, feces, vomit, skin scales, and other means.

Safe disposal of human waste is a fundamental need; poor sanitation is a primary cause of diarrhea disease in low-income communities.

The lack of quantitative data linking contaminated clothing to infection in the domestic setting makes it difficult to assess the extent of this risk.

[34][13][35] Infectious disease risks from contaminated clothing can increase significantly under certain conditions - for example, in healthcare situations in hospitals, care homes, and the domestic setting where someone has diarrhoea, vomiting, or a skin or wound infection.

As persistent nasal, skin, or bowel carriage in the healthy population spreads "silently" across the world, the risks from resistant strains in both hospitals and the community increases.

[34][39] Experience in the United States suggests that these strains are transmissible within families and in community settings such as prisons, schools, and sport teams.

The consequent variability in the data (i.e., the reduction in contamination on fabrics) in turn makes it extremely difficult to propose guidelines for laundering with any confidence.

For patients discharged from hospital, or being treated at home, special "medical hygiene" procedures may need to be performed for them, such as catheter or dressing replacement, which puts them at higher risk of infection.

The National Health Service (NHS) of England recommends not rinsing the mouth with water after brushing – only to spit out excess toothpaste.

This approach has been integrated into the Sustainable Development Goal Number 6 whose second target states: "By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations".

[63] Due to their close linkages, water, sanitation, hygiene are together abbreviated and funded under the term WASH in development cooperation.

[64] The most affected are people in developing countries who live in extreme conditions of poverty, normally peri-urban dwellers or rural inhabitants.

Providing access to sufficient quantities of safe water and facilities for a sanitary disposal of excreta, and introducing sound hygiene behaviors are important in order to reduce the burden of disease.

Social acceptance is an important part of encouraging people to use toilets and wash their hands, in situations where open defecation is still seen as a possible alternative, e.g. in rural areas of some developing countries.

[80] The earliest written account of elaborate codes of hygiene can be found in several Hindu texts, such as the Manusmriti and the Vishnu Purana.

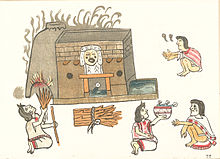

Bathing was not restricted to the elite, but was practiced by all people; the chronicler Tomás López Medel wrote after a journey to Central America that " and the custom of washing oneself is so quotidian [common] amongst the Indians, both of cold and hot lands, as is eating, and this is done in fountains and rivers and other water to which they have access, without anything other than pure water..."[83] The Mesoamerican bath, known as temazcal in Spanish, from the Nahuatl word temazcalli, a compound of temaz ("steam") and calli ("house"), consists of a room, often in the form of a small dome, with an exterior firebox known as texictle (teʃict͜ɬe) that heats a small portion of the room's wall made of volcanic rocks; after this wall has been heated, water is poured on it to produce steam, an action known as tlasas.

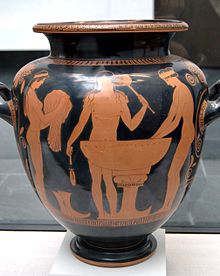

[84] Elaborate baths were constructed in urban areas to serve the public, who typically demanded the infrastructure to maintain personal cleanliness.

The complexes usually consisted of large, swimming pool-like baths, smaller cold and hot pools, saunas, and spa-like facilities where people could be depilated, oiled, and massaged.

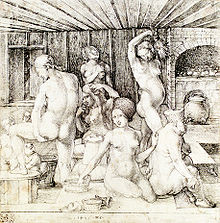

[92][93] Public bathhouses were common in medieval Christendom larger towns and cities such as Constantinople, Paris, Regensburg, Rome and Naples.

[95] In the 11th and 12th centuries, bathing was essential to the Western European upper class: the Cluniac monasteries (popular centers for resorting and retiring) were always equipped with bathhouses.

[96] The rules of the Augustinians and Benedictines contained references to ritual purification,[97] and, inspired by Benedict of Nursia, encouraged the practice of therapeutic bathing.

[99] In 14th century Tuscany, newlywed couples commonly took a bath together and we find an illustration of this custom in a fresco in the town hall of San Gimignano.

Though it took decades for his findings to gain wide acceptance, governments and sanitary reformers were eventually convinced of the health benefits of using sewers to keep human waste from contaminating the water.

The importance of hand washing for human health – particularly for people in vulnerable circumstances like mothers who had just given birth or wounded soldiers in hospitals – was first recognized in the mid 19th century by two pioneers of hand hygiene: the Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis who worked in Vienna, Austria, and Florence Nightingale, the English "founder of modern nursing".

[116] The Himba people of Namibia and Angola also utilized mixtures of smoke and otjitze treat skin diseases in regions where water is scarce.

Hard toilet soap with a pleasant smell was invented in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age when soap-making became an established industry.

[120] Industrially-manufactured bar soaps became available in the late 18th century, as advertising campaigns in Europe and America promoted popular awareness of the relationship between cleanliness and health.

Orthodox Judaism requires a mikveh bath following menstruation and childbirth, while washing the hands is performed upon waking up and before eating bread.