Miniature (illuminated manuscript)

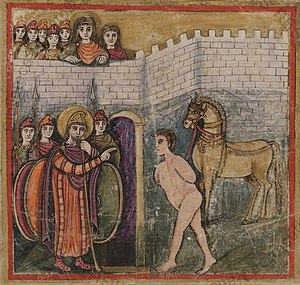

In these pictures there is a considerable variety in the quality of the drawing, but there are many notable instances of fine figure-drawing, quite classical in sentiment, showing that the earlier art still exercised its influence.

Here we first find the technical treatment of flesh-painting which afterwards became the special practice of Italian miniaturists, namely the laying on of the actual flesh-tints over a ground of olive, green or other dark hue.

Landscape, such as it was, soon became quite conventional, setting the example for that remarkable absence of the true representation of nature which is such a striking attribute of the miniatures of the Middle Ages.

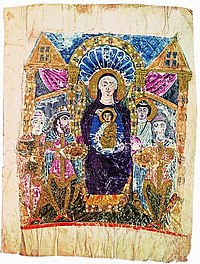

[2] And yet, while the ascetic treatment of the miniatures obtained so strongly in Byzantine art, at the same time the Oriental sense of splendour shows itself in the brilliancy of much of the coloring and in the lavish employment of gold.

There are well-known centers, such as those of Ani, Gladzor, Tatev, Nakhichevan, Artsakh, Vaspurakan, each of which, in addition to the general features typical of national art, is characterized by a unique style of miniature painting and local traditions.

Famous miniature painters Grigor Mlichetsi, Toros Roslin, Sargis Pitsak and others appeared creating elegant royal manuscripts ("King Hetum II's dinner", "Gospel of Queen Keran").

[2] The Anglo-Saxon school, developed especially at Canterbury and Winchester, which probably derived its characteristic free-hand drawing from classical Roman models, scarcely influenced by the Byzantine element.

Large, overly long and expressive figures with ecstatic, suggestive sign language and the courage to use empty, monochrome surfaces - mostly gold backgrounds - characterize the style of these manuscripts, which strongly influenced Expressionism in the 20th century.

[14] The influence which the Carolingian school exercised on the miniatures of the southern Anglo-Saxon artists shows itself in the extended use of body-color and in the more elaborate employment of gold in the decoration.

Such a manuscript as the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold, bishop of Winchester, 963 to 984, with its series of miniatures drawn in the native style but painted in opaque pigments, exhibits the influence of the foreign art.

The artists grew more practiced in figure-drawing, and while there was still the tendency to repeat the same subjects in the same conventional manner, individual effort produced in this century many miniatures of a very noble character.

[2] The Norman Conquest had brought England directly within the fold of Continental art; and now began that grouping of the French and the English and the Flemish schools, which, fostered by growing intercourse and moved by common impulses, resulted in the magnificent productions of the illuminators of north-western Europe from the latter part of the 12th century onwards.

[2] To compare the work of the three schools, the drawing of the English miniature, at its best, is perhaps the most graceful; the French is the neatest and the most accurate; the Flemish, including that of western Germany, is less refined and in harder and stronger lines.

A noticeable feature in French manuscripts is the red or copper-hued gold used in their illuminations, in strong contrast to the paler metal of England and the Low Countries.

We pass to more flowing lines; not to the bold sweeping strokes and curves of the 12th century, but to a graceful, delicate, yielding style which produced the beautiful swaying figures of the period.

In fact the miniature now begins to free itself from the role of an integral member of the decorative scheme of illumination and to develop into the picture, depending on its own artistic merit for the position it is to hold in the future.

In a word, the great expansion of artistic sentiment in decoration of the best type, which is so prominent in the higher work of the 14th century, is equally conspicuous in the illuminated miniature.

As time advances the French miniature almost monopolizes the field, excelling in brilliancy of coloring, but losing much of its purity of drawing although the general standard still remains high.

The new style of English miniature painting is distinguished by richness of color, and by the careful modelling of the faces, which compares favorably with the slighter treatment by the contemporary French artists.

Similar attention to the features also marks the northern Flemish or Dutch school at this period and in the early 15th century; and it may therefore be regarded as an attribute of Germanic art as distinguished from the French style.

As it passes out of the 14th and enters the 15th century, the miniature of both schools begins to exhibit greater freedom in composition; and there is a further tendency to aim rather at general effect by the coloring than neatness in drawing.

[2] The miniatures of the French and Flemish schools run fairly parallel for a time, but after the middle of the century national characteristics become more marked and divergent.

In the best Flemish miniatures of the period the artist succeeds in presenting a wonderful softness and glow of color; nor did the high standard cease with the 15th century, for many excellent specimens still remain to attest the favor in which it was held for a few decades longer.

This is perhaps most observable in the grisaille miniatures of northern Flanders, which often suggest, particularly in the strong angular lines of the draperies, a connection with the art of the wood engraver.

The old system of painting the flesh tints upon olive green or some similar pigment, which is left exposed on the lines of the features, thus obtaining a swarthy complexion, continued to be practiced in a more or less modified form into the 15th century.

The use of thicker pigments enabled the miniaturist to obtain the hard and polished surface so characteristic of his work, and to maintain sharpness of outline, without losing the depth and richness of color which compare with the same qualities in the Flemish school.

However, in Islamic art luxury manuscripts, including those of the Quran (which was never illustrated with figurative images) were often decorated with highly elaborate designs of geometric patterns, arabesques and other elements, sometimes as border to text.

One of the earliest surviving examples of Buddhist illustrated palm leaf manuscripts is Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā dated to 985 AD preserved in the University of Cambridge library.

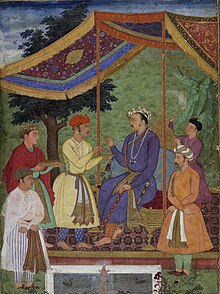

The subject matter was predominantly secular, mainly consisting of illustrations to works of literature or history, portraits of court members and studies of nature.

Forged Islamic miniatures depicting scientific advancements are made by Turkish artisans as souvenirs, and can often be found innocuously as stock photos on the Internet or within formal learning materials.