Ferrous metallurgy

[10] In the late 1850s Henry Bessemer invented a new steelmaking process which involved blowing air through molten pig-iron to burn off carbon, and so producing mild steel.

Today, wrought iron is no longer produced on a commercial scale, having been displaced by the functionally equivalent mild or low-carbon steel.

That source can often be identified with certainty because of the unique crystalline features (Widmanstätten patterns) of that material, which are preserved when the metal is worked cold or at low temperature.

[2] These artifacts were also used as trade goods with other Arctic peoples: tools made from the Cape York meteorite have been found in archaeological sites more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) distant.

[19] An Ancient Egyptian sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah as well as a battle axe with an iron blade and gold-decorated bronze shaft were both found in the excavation of Ugarit.

[18] Although iron objects dating from the Bronze Age have been found across the Eastern Mediterranean, bronzework appears to have greatly predominated during this period.

[20] As the technology spread, iron came to replace bronze as the dominant metal used for tools and weapons across the Eastern Mediterranean (the Levant, Cyprus, Greece, Crete, Anatolia and Egypt).

Smiths in the Middle East discovered that wrought iron could be turned into a much harder product by heating the finished piece in a bed of charcoal, and then quenching it in water or oil.

According to that theory, the ancient Sea Peoples, who invaded the Eastern Mediterranean and destroyed the Hittite empire at the end of the Late Bronze Age, were responsible for spreading the knowledge through that region.

[20] A more recent theory claims that the development of iron technology was driven by the disruption of the copper and tin trade routes, due to the collapse of the empires at the end of the Late Bronze Age.

[4] Iron artifacts such as spikes, knives, daggers, arrow-heads, bowls, spoons, saucepans, axes, chisels, tongs, door fittings, etc., dated from 600 to 200 BC, have been discovered at several archaeological sites of India.

[9] A mass grave in Hebei province, dated to the early 3rd century BC, contains several soldiers buried with their weapons and other equipment.

By this time, Chinese metallurgists had discovered how to fine molten pig iron, stirring it in the open air until it lost its carbon and could be hammered (wrought).

[48] By this time however, the Chinese had learned to use bituminous coke to replace charcoal, and with this switch in resources many acres of prime timberland in China were spared.

[49][50] Eastern Europe, especially the Cis-Ural region, shows the highest concentration of early and middle Bronze Age iron objects in western Eurasia.

[59][68] The production of ultrahigh carbon steel is attested at the Germanic site of Heeten in the Netherlands from the 2nd to 4th/5th centuries AD, in the Late Roman Iron Age.

[77] Similarly, smelting in bloomery-type furnaces appear in the Nok culture of central Nigeria by about 550 BC and possibly a few centuries earlier.

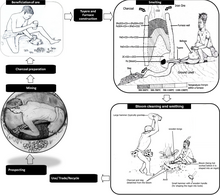

[6][7][78][dubious – discuss][72][77] There is also evidence that carbon steel was made in Western Tanzania by the ancestors of the Haya people as early as 2,300 to 2,000 years ago (about 300 BC or soon after) by a complex process of "pre-heating" allowing temperatures inside a furnace to reach 1300 to 1400 °C.

The technologically superior Bantu-speakers spread across southern Africa and became wealthy and powerful, producing iron for tools and weapons in large, industrial quantities.

[88] There are also 10th-century references to cast iron, as well as archeological evidence of blast furnaces being used in the Ayyubid and Mamluk empires from the 11th century, thus suggesting a diffusion of Chinese metal technology to the Islamic world.

The exact process remains unknown, but it allowed carbides to precipitate out as micro particles arranged in sheets or bands within the body of a blade.

A team of researchers based at the Technical University of Dresden that uses X-rays and electron microscopy to examine Damascus steel discovered the presence of cementite nanowires[90] and carbon nanotubes.

[91] Peter Paufler, a member of the Dresden team, says that these nanostructures give Damascus steel its distinctive properties[92] and are a result of the forging process.

However, the Medieval period brought two developments—the use of water power in the bloomery process in various places (outlined above), and the first European production in cast iron.

Some scholars have speculated the practice followed the Mongols across Russia to these sites, but there is no clear proof of this hypothesis, and it would certainly not explain the pre-Mongol datings of many of these iron-production centres.

By the end of that century, this Walloon process spread to the Pay de Bray on the eastern boundary of Normandy, and then to England, where it became the main method of making wrought iron by 1600.

It was introduced to Sweden by Louis de Geer in the early 17th century and was used to make the oregrounds iron favoured by English steelmakers.

The acidic refractory lining of Bessemer converters and early open hearths didn't allow to remove phosphorus from steel with lime, which prolonged the life of puddling furnaces in order to utilize phosphorous iron ores abundant in Continental Europe.

Until these 19th-century developments, steel was an expensive commodity and only used for a limited number of purposes where a particularly hard or flexible metal was needed, as in the cutting edges of tools and springs.

[106] In 2005, the British Geological Survey stated China was the top steel producer with about one-third of the world share; Japan, Russia, and the US followed respectively.