Tautochrone curve

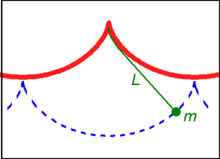

The curve is a cycloid, and the time is equal to π times the square root of the radius (of the circle which generates the cycloid) over the acceleration of gravity.

It was in the left hand try-pot of the Pequod, with the soapstone diligently circling round me, that I was first indirectly struck by the remarkable fact, that in geometry all bodies gliding along the cycloid, my soapstone for example, will descend from any point in precisely the same time.

The tautochrone problem, the attempt to identify this curve, was solved by Christiaan Huygens in 1659.

He proved geometrically in his Horologium Oscillatorium, originally published in 1673, that the curve is a cycloid.

Huygens also proved that the time of descent is equal to the time a body takes to fall vertically the same distance as diameter of the circle that generates the cycloid, multiplied by

Johann Bernoulli solved the problem in a paper (Acta Eruditorum, 1697).

After determining the correct path, Christiaan Huygens attempted to create pendulum clocks that used a string to suspend the bob and curb cheeks near the top of the string to change the path to the tautochrone curve.

Second, there were much more significant sources of timing errors that overwhelmed any theoretical improvements that traveling on the tautochrone curve helps.

Later, the mathematicians Joseph Louis Lagrange and Leonhard Euler provided an analytical solution to the problem.

For a simple harmonic oscillator released from rest, regardless of its initial displacement, the time it takes to reach the lowest potential energy point is always a quarter of its period, which is independent of its amplitude.

In the tautochrone problem, if the particle's position is parametrized by the arclength s(t) from the lowest point, the kinetic energy is then proportional to

One way the curve in the tautochrone problem can be an isochrone is if the Lagrangian is mathematically equivalent to a simple harmonic oscillator; that is, the height of the curve must be proportional to the arclength squared: where the constant of proportionality is

Compared to the simple harmonic oscillator's Lagrangian, the equivalent spring constant is

is not clear until we determine the exact analytical equation of the curve.

To solve for the analytical equation of the curve, note that the differential form of the above relation is which eliminates s, and leaves a differential equation for dx and dh.

This is the differential equation for a cycloid when the vertical coordinate h is counted from its vertex (the point with a horizontal tangent) instead of the cusp.

A particle on a 90° vertical incline undergoes full gravitational acceleration

, while a particle on a horizontal plane undergoes zero gravitational acceleration.

At intermediate angles, the acceleration due to "virtual gravity" by the particle is

, must obey the following differential equation: which, along with the initial conditions

The problem is now to construct a curve that will cause the mass to obey the above motion.

Newton's second law shows that the force of gravity and the acceleration of the mass are related by: The explicit appearance of the distance,

rolling along a horizontal line (a cycloid), with the circle center at the coordinates

that specifies the total time of descent for a given starting height, find an equation of the curve that yields this result.

, and since the particle is constrained to move along a curve, its velocity is simply

Likewise, the gravitational potential energy gained in falling from an initial height

, thus: In the last equation, we have anticipated writing the distance remaining along the curve as a function of height (

, recognized that the distance remaining must decrease as time increases (thus the minus sign), and used the chain rule in the form

to get the total time required for the particle to fall: This is called Abel's integral equation and allows us to compute the total time required for a particle to fall along a given curve (for which

and thus take the Laplace transform of both sides with respect to variable