Istrian–Dalmatian exodus

The emigrants, who had lived in the now Yugoslav territories of the Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner and Dalmatia, largely went to Italy, but some joined the Italian diaspora in the Americas, Australia and South Africa.

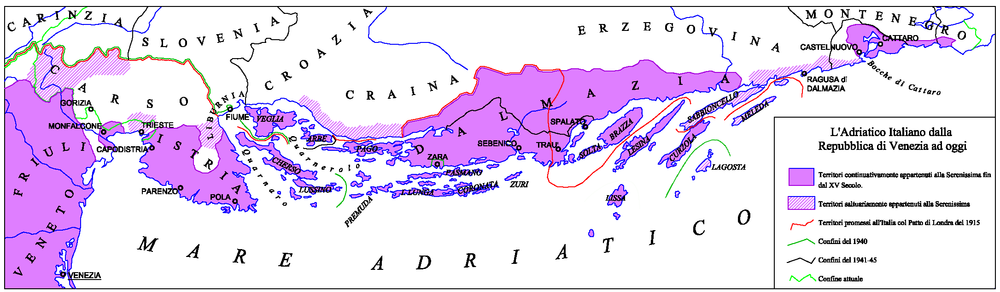

After World War I, the Kingdom of Italy annexed Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March and parts of Dalmatia including the city of Zadar.

At the end of World War II, under the Allies' Treaty of Peace with Italy, the former Italian territories in Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March and Dalmatia were assigned to now Communist-helmed Federal Yugoslavia, except for the Province of Trieste.

[23] In the Early Middle Ages, the territory of the Byzantine province of Dalmatia reached in the North up to the river Sava, and was part of the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum.

In the middle of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century began the Slavic migration, which caused the Romance-speaking population, descendants of Romans and Illyrians (speaking Dalmatian), to flee to the coast and islands.

[36] Republic of Venice influenced the neolatins of Istria and Dalmatia until 1797, when it was conquered by Napoleon: Capodistria and Pola were important centers of art and culture during the Italian Renaissance.

[40] However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria and Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic.

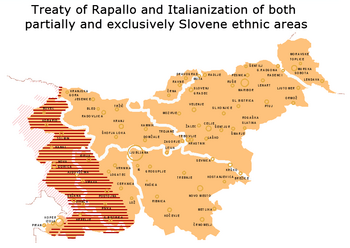

[41] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[42] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

[44] Bartoli's evaluation was followed by other claims that Auguste de Marmont, the French Governor General of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces commissioned a census in 1809 which found that Dalmatian Italians comprised 29% of the total population of Dalmatia.

[51] In 1915, Italy abrogated its alliance and declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire,[52] leading to bloody conflict mainly on the Isonzo and Piave fronts.

[53] In November 1918, after the surrender of Austria-Hungary, Italy occupied militarily Trentino Alto-Adige, the Julian March, Istria, the Kvarner Gulf and Dalmatia, all Austro-Hungarian territories.

Pula, for example, was badly affected by the drastic dismantling of its massive Austrian military and bureaucratic apparatus of more than 20,000 soldiers and security forces, as well as the dismissal of the employees from its naval shipyard.

All Slovenian and Croatian societies and sporting and cultural associations had to cease every activity in line with a decision of provincial fascist secretaries dated 12 June 1927.

[60] During World War II, in 1941, Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria occupied Yugoslavia, redrawing their borders to include former parts of the Yugoslavian state.

With the Treaties of Rome, the NDH agreed to cede to Italy Dalmatian territory, creating the second Governorate of Dalmatia, from north of Zadar to south of Split, with inland areas, plus nearly all the Adriatic islands and Gorski Kotar.

Following the surrender of Italy in 1943, much of Italian-controlled Dalmatia was liberated by the Partisans, then taken over by German forces in a brutal campaign, who then returned control to the puppet Independent State of Croatia.

Vis Island remained in Partisan hands, while Zadar, Rijeka, Istria, Cres, Lošinj, Lastovo and Palagruža became part of the German Operationszone Adriatisches Küstenland.

During the Croatian War of Independence, most of Dalmatia was a battleground between the Government of Croatia and the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), which aided the proto-state of Serbian Krajina, with much of the northern part of the region around Knin and the far south around, but not including, Dubrovnik being placed under the control of Serb forces.

These events were triggered by the atmosphere of settling accounts with the fascists; but, as it seems, they mostly proceeded from a preliminary plan which included several tendencies: endeavors to remove persons and structures who were in one way or another (regardless of their personal responsibility) linked with Fascism, with the Nazi supremacy, with collaboration and with the Italian state, and endeavors to carry out preventive cleansing of real, potential or only alleged opponents of the communist regime, and the annexation of the Julian March to the new SFR Yugoslavia.

[74][75] The term refers to the victims who were often thrown alive into foibas[76] (deep natural sinkholes; by extension, it also was applied to the use of mine shafts, etc., to hide the bodies).

[81] Economic insecurity, ethnic hatred and the international political context that eventually led to the Iron Curtain resulted in up to 350,000 people, mostly Italians, choosing to leave Istria (and even Dalmatia and northern Julian March).

In a 1991 interview with the Italian magazine Panorama, prominent Yugoslav political dissident Milovan Đilas claimed to have been dispatched to Istria alongside Edvard Kardelj in 1946, to organize anti-Italian propaganda.

The Wehrmacht was engaged in a front-wide retreat from the Yugoslav Partisans, along with the local collaborationist forces (the Ustaše, the Domobranci, the Chetniks, and units of Mussolini's Italian Social Republic).

Here more than 500 collaborators, Italian military and public servants were summarily executed; the leaders of the local Autonomist Party, including Mario Blasich and Nevio Skull, were also murdered.

According to the American historian Pamela Ballinger:[10]After 1945 physical threats generally gave way to subtler forms of intimidation such as the nationalization and confiscation of properties, the interruption of transport services (by both land and sea) to the city of Trieste, the heavy taxation of salaries of those who worked in Zone A and lived in Zone B, the persecution of clergy and teachers, and economic hardship caused by the creation of a special border currency, the Jugolira.The third part of the exodus took place after the Paris peace treaty, when Istria was assigned to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, except for a small area in the northwest part that formed the independent Free Territory of Trieste.

In connection with the exodus and during the period of communist Yugoslavia (1945–1991), the equality of ethno-nations and national minorities and how to handle inter-ethnic relations was one of the key questions of Yugoslav internal politics.

It further stated that "… each nationality has the sovereign right freely to use its own language and script, to foster its own culture, to set up organizations for this purpose, and to enjoy other constitutionally guaranteed rights…" (Article 274).

The same law created a special medal to be awarded to relatives of the victims: There is not yet complete agreement amongst historians about the causes and the events triggering the Istrian exodus.

On the other hand, Italians were pressured to leave quickly and en masse.Slovenian historian Darko Darovec[105] writes: It is clear, however, that at the peace conferences the new State borders were not being drawn using ideological criteria, but on the basis of national considerations.

After considerable government opposition,[116][117] with the imposition of a national filter that imposed the obligation to possess Italian citizenship for registration, in the end in 2013, it was opened hosting the first 25 children.