Italian entry into World War I

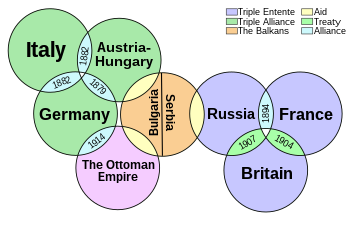

However, Russia had its own pro-Slavic interests in the Balkans; with her ally Serbia claiming much of the same territory sought by Italian irrendists, complicating negotiations.

In the face of insistence from London and Paris, Russia, by April 1915, abandoned its support for most of Serbia's claims and accepted terms for Italy's entry into the war, which would limit the Russian strategic presence in the postwar Adriatic.

Under the Peace Treaties of Saint-Germain, Rapallo and Rome, Italy gained a permanent seat in the League of Nations's executive council.

[10] Roy Pryce summarized the bitter experience: The Italian leadership was inexperienced, unfamiliar with international affairs, and often quite ill.

The King (since July 1900 it was Victor Emmanuel III) had nominal power over war and peace, but he had severe psychiatric problems in 1914, and in any case he turned over all major issues to his cabinet.

The decision for war was in the hands of Foreign Minister Antonio di San Giuliano, an experienced diplomat, cynical and cautious.

Public opinion wanted peace, and the leadership in Rome realized how poorly prepared the nation was in contrast to the powerhouses at war.

By late 1914, however, Prime Minister Antonio Salandra and Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino decided that major territorial gains were possible by joining the Allies, and would help calm extremely serious internal dissension, by bringing glory to the victorious army, as well as satisfying popular feeling by freeing Italian-speaking territories from Austrian rule.

Salandra boasted that the Pact of London was "the greatest, if not the first completely spontaneous act of foreign policy executed by Italy since the Risorgimento.

Freemasonry was an influential semi-secret force in Italian politics with a strong presence among professionals and the middle class across Italy, as well as among the leadership in parliament, public administration, and the army.

Freemasons took on the challenge of mobilizing the press, public opinion, and the leading political parties in support of Italy's joining the war as an ally of France and Great Britain.

Many elements of the left including syndicalists, republicans and anarchists protested against this and the Italian Socialist Party declared a general strike in Italy.

[20] The protests that ensued became known as "Red Week", as leftists rioted and various acts of civil disobedience occurred in major cities and small towns such as seizing railway stations, cutting telephone wires and burning tax-registers.

For the liberals, the war presented Italy a long-awaited opportunity to use an alliance with the Entente to gain territories from Austria-Hungary, which had long been part of Italian patriotic aims since unification.

Today, while Italy still wavers before the necessity imposed by history, the name of Garibaldi, resanctified by blood, rises again to warn her that she will not be able to defeat the revolution save by fighting and winning her national war.— Luigi Federzoni, 1915 [22]Mussolini used his new newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia and his strong oratorical skills to urge nationalists and patriotic revolutionary leftists to join the Allies: "Enough of Libya, and on to Trento and Trieste".

[23] Mussolini argued that it was in the interests of all socialists to join the war to tear down the aristocratic Hohenzollern dynasty of Germany because it was the enemy of all European workers.

[24] Mussolini and other nationalists warned the Italian government that Italy must join the war or face revolution and called for violence against pacifists and neutralists.

[26] Italy joined the war in order to seek territories deemed part of the nation still occupied by foreign powers, as well as to dissolve the intense internal disharmony through unity of purpose among the people.

[27][28] By August 1914 Russia was eager for Italy's entry into the war, expecting it would open a new front that would paralyze any Austrian offensive.

The pact ensured Italy the right to attain all Italian-populated lands it wanted from Austria-Hungary, as well as concessions in the Balkan Peninsula and suitable compensation for any territory gained by the Allies from Germany in Africa.

Giolitti claimed that Italy would fail in the war, predicting high numbers of mutinies, Austro-Hungarian occupation of even more Italian territory.