Italian orthography

This article focuses on the writing of Standard Italian, based historically on the Florentine variety of Tuscan.

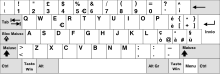

The letters J, K, W, X and Y are not part of the proper alphabet, but appear in words of ancient Greek origin (e.g. Xilofono), loanwords (e.g. "weekend"),[2] foreign names (e.g. John), scientific terms (e.g. km) and in a handful of native words—such as the names Kalsa, Jesolo, Bettino Craxi, and Cybo, which all derive from regional languages.

The short–long length contrast is phonemic, e.g. ritto [ˈritto], "upright", vs. rito [ˈriːto], "rite, ritual", carro [ˈkarro], "cart, wagon", vs. caro [ˈkaːro], "dear, expensive".

There is typically no orthographic distinction between the open and close sounds represented, although accent marks are used in certain instances (see below).

Many exceptions exist (e.g. attuale, deciduo, deviare, dioscuro, fatuo, iato, inebriare, ingenuo, liana, proficuo, riarso, viaggio).

The phonemicity of the affricates can be demonstrated with minimal pairs: The trigraphs ⟨cch⟩ and ⟨ggh⟩ are used to indicate geminate /kk/ and /ɡɡ/, when they occur before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩; e.g. occhi /ˈɔkki/ "eyes", agghindare /aɡɡinˈdare/ "to dress up".

The double letters ⟨cc⟩ and ⟨gg⟩ before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩ and ⟨cci⟩ and ⟨ggi⟩ before other vowels represent the geminated affricates /ttʃ/ and /ddʒ/, e. g. riccio, "hedgehog", peggio, "worse".

By way of exception, ⟨gl⟩ before ⟨i⟩ represents /ɡl/ in some words derived from Greek, such as glicine, "wisteria", from learned Latin, such as negligente, "negligent", and in a few adaptations from other languages such as glissando /ɡlisˈsando/, partially italianised from French glissant.

⟨z⟩ represents a dental affricate consonant; either /dz/ (zanzara /dzanˈdzara/) or /ts/ (canzone /kanˈtsone/), depending on context, although there are few minimal pairs.

Most words are consistently pronounced with /tts/ or /ddz/ throughout Italy in the standard language (e.g. gazza /ˈɡaddza/ "magpie", tazza /ˈtattsa/ "mug"), but a few words, such as frizzare, "effervesce, sting", exist in both voiced and voiceless forms, differing by register or by geographic area, while others have different meanings depending on whether they are pronounced in voiced or voiceless form (e.g. razza: /ˈrattsa/ (race, breed) or /ˈraddza/ (ray, skate)).

Indirizzare, for example, of Latin origin reconstructed as *INDIRECTIARE, has /tts/ in all forms containing the root indirizz-.

[9][10] ⟨h⟩ is used in some loanwords, by far the most common of which is hotel,[4] but also handicap, habitat, hardware, hall ("lobby, foyer"), hamburger, horror, hobby.

[11] Silent ⟨h⟩ is also found in some Italian toponyms: Chorio, Dho, Hano, Mathi, Noha, Proh, Rho, Roghudi, Santhià, Tharros, Thiene, Thiesi, Thurio, Vho; and surnames: Dahò, Dehò, De Bartholomaeis, De Thomasis, Matthey, Rahò, Rhodio, Tha, Thei, Theodoli, Thieghi, Thiella, Thiglia, Tholosano, Thomatis, Thorel, Thovez.

[12] The letter ⟨j⟩ (I lunga, "long I", or gei) is not considered part of the standard Italian alphabet; however, it is used in some Latin words, in proper nouns (such as Jesi, Letojanni, Juventus, etc.

), in words borrowed from foreign languages (most common: jeans, but also jazz, jet, jeep, banjo),[13] and in an archaic spelling of Italian.

Until the 19th century, ⟨j⟩ was used in Italian instead of ⟨i⟩ in word-initial rising diphthongs, as a replacement for final -⟨ii⟩, and between vowels (as in Savoja); this rule was quite strict in official writing.

Since final ⟨o⟩ is hardly ever close-mid, ⟨ó⟩ is very rarely encountered in written Italian (e.g. metró, "subway", from the original French pronunciation of métro with a final-stressed /o/).

The accents may also be used to differentiate minimal pairs within Italian (for example pèsca, "peach", vs. pésca, "fishing"), but in practice this is limited to didactic texts.

[citation needed] The circumflex accent (ˆ) can be used to mark the contraction of two unstressed vowels /ii/ ending a word, normally pronounced [i], so that the plural of studio, "study, office", may be written ⟨studi⟩, ⟨studii⟩ or ⟨studî⟩.

The form with circumflex is found mainly in older texts, although it may still appear in contexts where ambiguity might arise from homography.

Lines 1–3 of Canto 1 of the Inferno, Part 1 of the Divina Commedia by Dante Alighieri, a highly influential poem.

Translation (Longfellow): "Midway upon the journey of our life \ I found myself in a dark wood \ for the straight way was lost.