Jesus (name)

[3] The vocative form Jesu, from Latin Iesu, was commonly used in religious texts and prayers during the Middle Ages, particularly in England, but gradually declined in usage as the English language evolved.

There have been various proposals as to the literal etymological meaning of the name Yəhôšuaʿ (Joshua, Hebrew: יְהוֹשֻׁעַ), including Yahweh/Yehowah saves, (is) salvation, (is) a saving-cry, (is) a cry-for-saving, (is) a cry-for-help, (is) my help.

Yeshua was in common use by Jews during the Second Temple period and many Jewish religious figures bear the name, including Joshua in the Hebrew Bible and Jesus in the New Testament.

[10] However, both the Western and Eastern Syriac Christian traditions use the Aramaic name ܝܫܘܥ (in Hebrew script: ישוע) Yeshuʿ and Yishoʿ, respectively, including the ʿayin.

[15] By the time the New Testament was written, the Septuagint had already transliterated ישוע (Yeshuaʿ) into Koine Greek as closely as possible in the 3rd-century BCE, the result being Ἰησοῦς (Iēsous).

The diphthongal [a] vowel of Masoretic Yehoshuaʿ or Yeshuaʿ would not have been present in Hebrew/Aramaic pronunciation during this period, and some scholars believe some dialects dropped the pharyngeal sound of the final letter ע ʿayin [ʕ], which in any case had no counterpart in ancient Greek.

The Latin name has an irregular declension, with a genitive, dative, ablative, and vocative of Jesu, accusative of Jesum, and nominative of Jesus.

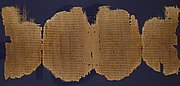

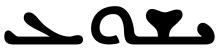

Similarly, Greek minuscules were invented about the same time, prior to that the name was written in capital letters (ΙΗϹΟΥϹ) or abbreviated as (ΙΗϹ) with a line over the top, see also Christogram.

At once it achieves the two goals of affirming Jesus as the savior and emphasizing that the name was not selected at random, but based on a heavenly command.

[24] John Wycliffe (1380s) used the spelling Ihesus and also used Ihesu ('J' was then a swash glyph variant of 'I', not considered to be a separate letter until the 1629 Cambridge 1st Revision King James Bible where "Jesus" first appeared) in oblique cases, and also in the accusative, and sometimes, apparently without motivation, even for the nominative.