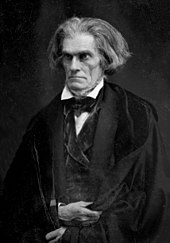

John C. Calhoun

In contrast with his previous nationalist sentiments, Calhoun vigorously supported South Carolina's right to nullify federal tariff legislation that he believed unfairly favored the North, which put him into conflict with Unionists such as Jackson.

Calhoun served as Secretary of State under President John Tyler from 1844 to 1845, and in that role supported the annexation of Texas as a means to extend the Slave Power and helped to settle the Oregon boundary dispute with Britain.

[5][6] Patrick, a prominent member of the tight-knit Scotch-Irish community on the frontier who worked as surveyor and farmer, was elected to the South Carolina Legislature in 1763 and acquired ownership over slave plantations.

Biographer John Niven says: Calhoun admired Dwight's extemporaneous sermons, his seemingly encyclopedic knowledge, and his awesome mastery of the classics, of the tenets of Calvinism, and of metaphysics.

"Young man," retorted Dwight, "your talents are of a high order and might justify you for any station, but I deeply regret that you do not love sound principles better than sophistry—you seem to possess a most unfortunate bias for error.

By 1814 the British were thwarted at the invasions of New York and Baltimore, but Napoleon Bonaparte capitulated, meaning America would now face Britain's formidable reinforcement with units previously committed to Europe if the war were to continue.

"[36] John Quincy Adams concluded in 1821 that "Calhoun is a man of fair and candid mind, of honorable principles, of clear and quick understanding, of cool self-possession, of enlarged philosophical views, and ardent patriotism.

His priority was an effective navy, including steam frigates, and in the second place a standing army of adequate size—and as further preparation for an emergency, "great permanent roads", "a certain encouragement" to manufacturers, and a system of internal taxation that would not collapse from a war-time shrinkage of maritime trade, like customs duties.

[43] However, Calhoun supported the execution of Alexander Arbuthnot and Robert Ambrister, two British soldiers living in Florida who were accused of inciting the Seminole to make war against the United States.

[49] Calhoun also opposed President Adams' plan to send a delegation to observe a meeting of South and Central American leaders in Panama, believing that the United States should stay out of foreign affairs.

[18][54] Jackson, who loved to personalize disputes,[55] also saw the Petticoat affair as a direct challenge to his authority, because it involved lower-ranking executive officials and their wives seeming to contest his ability to choose whomever he wanted for his cabinet.

Many cabinet members were Southern and could be expected to sympathize with such concerns, especially Treasury Secretary Samuel D. Ingham, who was allied with Calhoun and believed that he, not Van Buren, should succeed Jackson as president.

Calhoun had been assured that the northeastern interests would reject the Tariff of 1828, exposing pro-Adams New England congressmen to charges that they selfishly opposed legislation popular among Jacksonian Democrats in the west and mid-Atlantic States.

[80] The South Carolina newspaper City Gazette commented on the change: It is admitted that the former gentleman [Hayne] is injudiciously pitted against Clay and Webster and, nullification out of the question, Mr. Calhoun's place should be in front with these formidable politicians.

[81]Biographer John Niven argues "that these moves were part of a well-thought-out plan whereby Hayne would restrain the hotheads in the state legislature and Calhoun would defend his brainchild, nullification, in Washington against administration stalwarts and the likes of Daniel Webster, the new apostle of northern nationalism.

[83][84] When Calhoun took his seat in the Senate on December 29, 1832, his chances of becoming president were considered poor due to his involvement in the Nullification Crisis, which left him without connections to a major national party.

[9] Calhoun resigned from the Senate on March 3, 1843, four years before the expiration of his term, and returned to Fort Hill to prepare an attempt to win the Democratic nomination for the 1844 presidential election.

[93] He named Calhoun Secretary of State on April 10, 1844, following the death of Abel P. Upshur, one of six people killed when a cannon exploded during a public demonstration in the USS Princeton disaster.

The State Department's secret negotiations with the Texas republic had proceeded despite explicit threats from a suspicious Mexican government that an unauthorized seizure of its northern district of Coahuila y Tejas would be equivalent to an act of war.

[111] Calhoun's Pakenham letter, and its identification with proslavery extremism, moved the presumptive Democratic Party nominee, the northerner Martin Van Buren, into denouncing annexation.

[112]In the general election, Calhoun offered his endorsement to Polk on condition that he support the annexation of Texas, oppose the Tariff of 1842, and dissolve the Washington Globe, the semi-official propaganda organ of the Democratic Party headed by Francis Preston Blair.

[121] The Compromise of 1850, devised by Clay and Stephen A. Douglas, a first-term Democratic senator from Illinois, was designed to solve the controversy over the status of slavery in the vast new territories acquired from Mexico.

During the Civil War, a group of Calhoun's friends were concerned about the possible desecration of his grave by Federal troops and, during the night, removed his coffin to a hiding place under the stairs of the church.

He ran away for no other cause, but to avoid a correction for some misconduct, and as I am desirous to prevent a repetition, I wish you to have him lodged in Jail for one week, to be fed on bread and water and to employ some one for me to give him 30 lashes well laid on, at the end of the time.

[138]Calhoun was consistently opposed to the War with Mexico, arguing that an enlarged military effort would only feed the alarming and growing lust of the public for empire regardless of its constitutional dangers, bloat executive powers and patronage, and saddle the republic with a soaring debt that would disrupt finances and encourage speculation.

[158] Chief Justice Roger B. Taney used Calhoun's arguments in his decision in the 1857 Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which he ruled that the federal government could not prohibit slavery in any of the territories.

[162] In 1887, at the height of the Jim Crow era, white segregationists erected a monument to Calhoun in Marion Square in Charleston, South Carolina; the base was within easy reach and the local black population defaced it.

He strove, schemed, dreamed, lived only for the presidency; and when he despaired of reaching that office through honorable means, he sought to rise upon the ruins of his country-thinking it better to reign in South Carolina than to serve in the United States.

[79]Writing more than thirty years after Calhoun's death, James G. Blaine portrayed him as a mix of personal integrity and wrongheaded ideology: Deplorable as was the end to which his teachings led, he could not have acquired the influence he wielded over millions of men unless he had been gifted with acute intellect, distinguished by moral excellence, and inspired by the sincerest belief in the righteousness of his cause.

The racially motivated Charleston church shooting in South Carolina in June 2015 reinvigorated demands for the removal of monuments dedicated to prominent pro-slavery and Confederate States figures.