Edward I of England

Edward is credited with many accomplishments, including restoring royal authority after the reign of Henry III and establishing Parliament as a permanent institution, which allowed for a functional system for raising taxes and reforming the law through statutes.

At the same time, he is often condemned for vindictiveness, opportunism and untrustworthiness in his dealings with Wales and Scotland, coupled with a colonialist approach to their governance and to Ireland, and for antisemitic policies leading to the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290.

[23] In Gascony, Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, had been appointed as royal lieutenant in 1253 and drew its income, so Edward derived neither authority nor revenue from this province.

[42] He reunited with some of the men he had alienated the year before – including Henry of Almain and John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey – and retook Windsor Castle from the rebels.

[57][d] In April it seemed as if the Earl of Gloucester would take up the cause of the reform movement, and civil war would resume, but after a renegotiation of the terms of the Dictum of Kenilworth, the parties came to an agreement.

[64] In May 1270, Parliament granted a tax of one-twentieth of all movable property; in exchange the King agreed to reconfirm Magna Carta, and to impose restrictions on Jewish money lending.

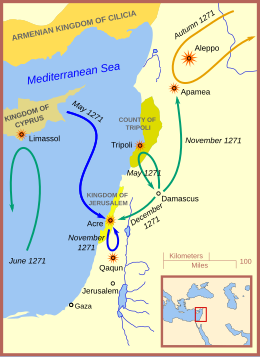

Edward's men were an important addition to the garrison, but they stood little chance against Baibars's superior forces, and an initial raid at nearby St Georges-de-Lebeyne in June was largely futile.

[105] On 6 November, while John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury, was conducting peace negotiations, Edward's commander of Anglesey, Luke de Tany, carried out a surprise attack.

[113][l] An extensive project of castle building was also initiated, under the direction of James of Saint George,[115] a prestigious architect Edward had met in Savoy on his return from the crusade.

[151] He was deeply affected by her death,[152] and displayed his grief by ordering the construction of twelve so-called Eleanor crosses,[153] one at each place where her funeral cortège stopped for the night.

[178] A further provocation came in a case brought by Macduff, son of Malcolm II, Earl of Fife, in which Edward demanded that Balliol appear in person before the English Parliament to answer the charges.

[196] Historian Michael Prestwich believes Edward met contemporary expectations of kingship in his role as an able, determined soldier and in his embodiment of shared chivalric ideals.

[197] In religious observance he fulfilled the expectations of his age: he attended chapel regularly, gave alms generously and showed a fervent devotion to the Virgin Mary and Saint Thomas Becket.

[235] There were several ways through which the King could raise money for war, including customs duties, loans and lay subsidies, which were taxes collected at a certain fraction of the moveable property of all laymen who held such assets.

[252] Over-taxation of the Jews forced them to sell their debt bonds at cut prices, which was exploited by the crown to transfer vast land wealth from indebted landholders to courtiers and his wife, Eleanor of Provence, causing widespread resentment.

[270] He helped pay for the renovation of the tomb of Little Saint Hugh, a child falsely claimed to have been ritually crucified by Jews, in the same style as the Eleanor crosses, to take political credit for his actions.

[275] The funnelling of revenue to Edward's wars left Irish castles, bridges and roads in disrepair, and alongside the withdrawal of troops to be used against Wales and Scotland and elsewhere, helped induce lawless behaviour.

[281] Conflict was firmly entrenched by the time of the 1297 Irish Parliament, which attempted to create measures to counter disorder and the spread of Gaelic customs and law, while the results of the distress included many abandoned lands and villages.

[294] In July, Bigod and Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford and Constable of England, drew up a series of complaints known as the Remonstrances, in which objections to the high level of taxation were voiced.

[300] Edward signed the Confirmatio cartarum – a confirmation of Magna Carta and its accompanying Charter of the Forest – and the nobility agreed to serve with the King on a campaign in Scotland.

[307] Edward believed that he had completed the conquest of Scotland when he left the country in 1296, but resistance soon emerged under the leadership of Andrew de Moray in the north and William Wallace in the south.

[312] Even though Edward campaigned in Scotland in 1300, when he successfully besieged Caerlaverock Castle and in 1301, the Scots refused to engage in open battle again, preferring instead to raid the English countryside in smaller groups.

[325] His younger brother Neil was executed by being hanged, drawn, and quartered; he had been captured after he and his garrison held off Edward's forces who had been seeking his wife, daughter and sisters.

[350] The influential Victorian historian William Stubbs suggested that Edward had actively shaped national history, forming English laws and institutions, and helping England to develop a parliamentary and constitutional monarchy.

[353] Tout came to view Edward as a self-interested, conservative leader, using the parliamentary system as "the shrewd device of an autocrat, anxious to use the mass of the people as a check upon his hereditary foes among the greater baronage.

[358] F. M. Powicke's volumes, published in 1947 and 1953, forming the standard works on Edward for several decades, were largely positive in praising the achievements of his reign, and his focus on justice and the law.

[359] In 1988, Michael Prestwich produced an authoritative biography of the King, focusing on his political career, still portraying him in sympathetic terms, but highlighting some of the consequences of his failed policies.

[365] G. W. S. Barrow counters that Edward's contemporaries knew the "meaning of compassion, magnanimity, justice and generosity", that he rarely rose above minimum moral standards of his time, but rather showed a highly vindictive streak, and is among the "boldest opportunists of English political history".

"[367] In 2014, Andrew Spencer and Caroline Burt reassessed Edward's reign from an English constitutional perspective, asserting that he had a personal role in reform and a moral purpose in his leadership.

[379] They emphasise the growing power of the law, centralised state and crown across Europe, and see Edward as asserting his rights within England and the other nations of Britain and Ireland.

Edward I