Kingdom of Kush

[8] The city-state of Kerma emerged as the dominant political force between 2450 and 1450 BC, controlling the Nile Valley between the first and fourth cataracts, an area as large as Egypt.

The Egyptians were the first to identify Kerma as "Kush" probably from the indigenous ethnonym "Kasu", over the next several centuries the two civilizations engaged in intermittent warfare, trade, and cultural exchange.

Following Egypt's disintegration amid the Late Bronze Age collapse, the Kushites reestablished a kingdom in Napata (now modern Karima, Sudan).

At the end of the Second Intermediate Period (mid-sixteenth century BC), Egypt faced the twin existential threats—the Hyksos in the North and the Kushites in the South.

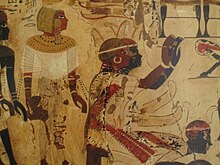

Taken from the autobiographical inscriptions on the walls of his tomb-chapel, the Egyptians undertook campaigns to defeat Kush and conquer Nubia under the rule of Amenhotep I (1514–1493 BC).

In Ahmose's writings, the Kushites are described as archers, "Now after his Majesty had slain the Bedoin of Asia, he sailed upstream to Upper Nubia to destroy the Nubian bowmen.

The Assyrians, from the tenth century BC onwards, had once more expanded from northern Mesopotamia, and conquered a vast empire, including the whole of the Near East, and much of Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, the Caucasus and early Iron Age Iran.

[39] There are various theories (Taharqa's army,[40] disease, divine intervention, Hezekiah's surrender or agreeing to pay tribute) as to why the Assyrians failed to take the city.

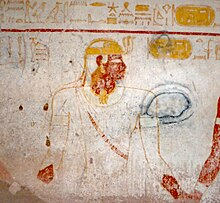

The Kushite pharaohs built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, and Jebel Barkal.

[46][47][48] The Kushites developed their own script, the Meroitic alphabet, which was influenced by Egyptian writing systems c. 700–600 BC, although it appears to have been wholly confined to the royal court and major temples.

[citation needed] The relatively small Assyrian force had first defeafed Canaanite and Arab tribes in the region and then immediately marched at great speed on Ashkelon, leaving them exhausted.

[35]: 121 Taharqa's successor, Tantamani sailed north from Napata, through Elephantine, and to Thebes with a large army, where he was "ritually installed as the king of Egypt.

"[50] From Thebes, Tantamani began his attempt at reconquest[50] and regained control of a part of southern Egypt as far as Memphis from the native Egyptian puppet rulers installed by the Assyrians.

[55] For example, the DNa inscription of Darius I (r. 522–486 BC) on his tomb at Naqsh-e Rustam mentions Kūšīyā (Old Persian cuneiform: 𐎤𐎢𐏁𐎡𐎹𐎠, pronounced Kūshīyā) among the territories being "ruled over" by the Achaemenid Empire.

[56][55] Derek Welsby states "scholars have doubted that this Persian expedition ever took place, but... archaeological evidence suggests that the fortress of Dorginarti near the second cataract served as Persia's southern boundary.

The stele of king Harsiotef, who from around 400 BC ruled for at least 35 years, reports how he fought a multitude of campaigns against enemies ranging from Meroe in the south to Lower Nubia in the north while also donating to temples throughout Kush.

During this same period, the Kushite authority may have extended some 1,500 km along the Nile River valley from the Egyptian frontier in the north to areas far south of modern Khartoum and probably also substantial territories to the east and west.

[65] Remarkably, the destruction of the capital of Napata was not a crippling blow to the Kushites and did not frighten Candace enough to prevent her from again engaging in combat with the Roman military.

[66]: 149 Alerted to the advance, Gaius Petronius, prefect of Roman Egypt, again marched south and managed to reach Qasr Ibrim and bolster its defenses before the invading Kushites arrived.

[66]: 150–151 Nero sent two centurions upriver as far as Bahr el Ghazal River in 66 AD in an attempt to discover the source of the Nile, per Seneca,[61]: 43 or plan an attack, per Pliny.

Kush began to fade as a power by the first or second century AD, sapped by the war with the Roman province of Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.

[83] A bowl from a 4th-century elite burial in el-Hobagi features a Meroitic-Nubian inscription mentioning a "king", but identifying the interred individual and the polity he ruled over remains problematic.

[94][95] Claude Rilly proposes that Meroitic, like the Nobiin language, belongs to the Eastern Sudanic branch of the Nilo-Saharan family, based in part on its syntax, morphology, and known vocabulary.

The introduction of this machine had a decisive influence on agriculture especially in Dongola as this wheel lifted water 3 to 8 meters with much less expenditure of labor and time than the shaduf, which was the previous chief irrigation device in the kingdom.

Following his army's lack of success he undertook the personal supervision of operations including the erection of a siege tower from which Kushite archers could fire down into the city.

[118] During the Bronze Age, Nubian ancestors of the Kingdom of Kush built speoi (a speos is a temple or tomb cut into a rock face) between 3700 and 3250 BC.

Tombs became progressively larger during the 25th dynasty, culminating in Taharqa's underground rectangular building with "aisles of square piers...the whole being cut from the living rock.

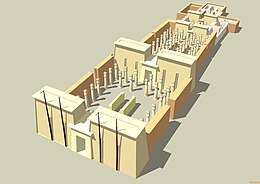

"[51]: 118 Temples for major Egyptian deities were built on "a system of internal harmonic proportions" based on "one or more rectangles each with sides in the ratio of 8:5"[51]: 133 [125] Kush also invented Nubian vaults.

Pyramids are "the archetypal tomb monument of the Kushite royal family" and found at "el Kurru, Nuri, Jebel Barkal, and Meroe.

[127] On account of the Kingdom of Kush's proximity to Ancient Egypt – the first cataract at Elephantine usually being considered the traditional border between the two polities – and because the 25th dynasty ruled over both states in the eighth century BC, from the Rift Valley to the Taurus mountains, historians have closely associated the study of Kush with Egyptology, in keeping with the general assumption that the complex sociopolitical development of Egypt's neighbors can be understood in terms of Egyptian models.