Innate lymphoid cell

ILC1 and NK cell lineages diverge early in their developmental pathways and can be discriminated by their difference in dependence on transcription factors, their cytotoxicity, and their resident marker expression.

They are involved in the formation of secondary lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches by promoting lymphoid tissue development, which they do through the action of lymphotoxin, a member of the TNF superfamily.

[4] ILCs are recombination activating gene (RAG)- independent, instead, they rely on cytokine signalling through the common cytokine- receptor gamma chain and the JAK3 kinase pathway for development.

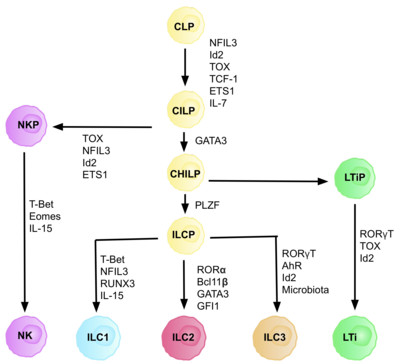

Each stage of differentiation is dependent on expression of different transcription factors, including: NFIL3, TCF-1, ETS1, GATA3, PLZF, T-bet, Eomes, RUNX3, RORα, Bcl11b, Gfi1, RORγt, and AhR.

Studies suggest primary site of ILC development is in the liver in the foetus, and the bone marrow in adults, as this is where CLPs, NKPs, and CHILPs have been found.

The microenvironment of the tissue they reside in determines and fine- tunes the expression of the diverse ILC profiles, facilitating their interaction in multiple effector functions.

ILC3s regulate the containment of commensal bacteria in the lumen, allowing it to be exposed to lamina propria phagocytes, leading to T cell priming.

Although they can present antigens, via MHC class II receptors, ILCs lack co-stimulatory molecules, and therefore play a role in T cell anergy, promoting tolerance to beneficial commensals.

[41][42] ILC3s interact with the enteric nervous system to maintain intestinal homeostasis, as in response to bacteria, glial cells in the lamina propria secrete neurotrophic factors, which through the neuroregulatory receptor RET, induce IL-22 production by ILC3s.

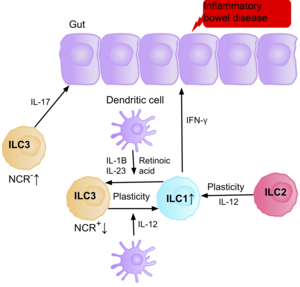

[6] Retinoic acid, produced by dendritic cells, promotes the expression of gut homing receptors on ILC1s, and ILC3s, and enhances ILC3 function, by upregulating RORγt, and IL-22.

Conversely, retinoic acid suppresses ILC2 proliferation by down regulating IL-7Ra, and deprivation of vitamin A has been shown to enhance ILC2- mediated resistance to helminth infection in mice.

The production of IL-17 can support the growth of tumors and metastasis since it induces blood vessel permeability, however, the upregulation of MHC Class II on their surface can prime CD4+ T cells, having an anti-tumorigenic effect.

The production of tryptophan metabolites causes the AhR transcription factor to induce IL-22 expression, maintaining the number of ILC3s present, and therefore intestinal homeostasis.

Dietary nutrient availability therefore modifies the ILC immune response to infection and inflammation, highlighting the importance of a balanced and healthy diet.

[65] ILC1s and NK cells secrete IFN-γ in response to viral infection in the lungs, including rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

[39] In response to the release of IL-33 by the epidermis, ILC2s secrete high levels amphiregulin, a critical epidermal growth factor, therefore contributing to cutaneous wound healing.

ILC2s interact with neurons in the respiratory tract by the proximity to nerve fibers, and lung resident IL-5-producing ILC2s are found in collagen-rich regions close to the confluence of medium-sized blood vessels and airways.

Its deletion resulted in the dysregulation of ILC3 caused by epigenetic changes, driving the expression of IL-22 and contributing to the alteration of the microbiome, epithelial cells, and a disrupted uptake of lipids in the intestine.

On the other hand, the deletion of Nr1d1, a protein implicated in regulating circadian metabolic responses, resulted in the reduction of NCR+ ILC3 and the increase of IL-17 production, while did not affect the LTi-like ILC3.

It is believed the increase in ILC2s present correlates with the severity of the disease, and evidence confirms some ‘allergen- experienced’ ILC2s persist after the resolution of the initial inflammation, portraying similarities to memory T cells.

The integration of information collected through these numerous inputs allows NK cells to maintain self-tolerance and recognize self-cell stress signals.

NK cell dysregulation has been implicated in a number of autoimmune disorders including multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type I diabetes mellitus.

[76] Research suggests IL-17 producing NCR- ILC3s contribute to the pathophysiology of IBD due to their increased abundance in the intestine of patients with Crohn’s disease.

[39] Evidence also suggests the ability of ILC2s to acquire the pro-inflammatory phenotype, with ILC2s producing IFN-γ present in the intestine of patients with Crohn’s disease, in response to certain environmental factors such as cytokines.

[10] ILC1s as a key regulatory of adipose tissue inflammation, are therefore a potential therapeutic target for treating people with liver disease or metabolic syndrome.

[13][47] This is also a common feature in T cells, and it is believed this plasticity is critical to allow our immune system to fine tune responses to so many different pathogens.

[85] There is increasing evidence indicating that ILC2s also have a certain degree of plasticity, with studies confirming their ability to convert into ILC1s and ILC3s upon exposure to specific environmental stimuli such as cytokines, or notch ligands.

In patients with Crohn’s disease, the increase of ILC1 at the expense of ILC3 possibly by the production of IL-2 from T regulatory cell, leading to a pathogenic state and inflammatory events.

Although the interconversion of ILC1 and ILC3 is modulated by the differential expression of RORγt and T-bet, different questions remain that need to be explained to understand the inflammation caused by these cells.

[87] In certain environments, such as inflammation, chronic disease, or tumor microenvironments, activated NK cells can start to express CD49a, and CXCR6, common ILC1 markers, strengthening their plastic properties.