Langmuir–Blodgett film

A Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) film is an emerging kind of 2D materials to fabricate heterostructures for nanotechnology, formed when Langmuir films—or Langmuir monolayers (LM)—are transferred from the liquid-gas interface to solid supports during the vertical passage of the support through the monolayers.

A monolayer is adsorbed homogeneously with each immersion or emersion step, thus films with very accurate thickness can be formed.

The monolayers are assembled vertically and are usually composed either of amphiphilic molecules (see chemical polarity) with a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail (example: fatty acids) or nowadays commonly of nanoparticles.

[1] Langmuir–Blodgett films are named after Irving Langmuir and Katharine B. Blodgett, who invented this technique while working in Research and Development for General Electric Co. Advances to the discovery of LB and LM films began with Benjamin Franklin in 1773 when he dropped about a teaspoon of oil onto a pond.

With the help of her kitchen sink, Agnes Pockels showed that area of films can be controlled with barriers.

His observations indicated that chain length did not impact the affected area since the organic molecules were arranged vertically.

Blodgett initially went to seek for a job at General Electric (GE) with Langmuir during her Christmas break of her senior year at Bryn Mawr College, where she received a BA in Physics.

However, breakthroughs in surface chemistry happened after she received her PhD degree in 1926 from Cambridge University.

Through this work in surface chemistry and with the help of Blodgett, Langmuir was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1932.

Langmuir films are formed when amphiphilic (surfactants) molecules or nanoparticles are spread on the water at an air–water interface.

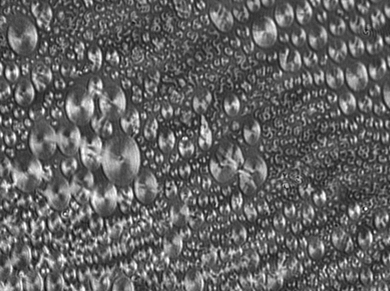

For very small concentrations, far from the surface density compatible with the collapse of the monolayer (which leads to polylayers structures) the surfactant molecules execute a random motion on the water–air interface.

Further compression of the surfactant molecules on the surface shows behavior similar to phase transitions.

The ‘gas’ gets compressed into ‘liquid’ and ultimately into a perfectly closed packed array of the surfactant molecules on the surface corresponding to a ‘solid’ state.

Langmuir–Blodgett troughs Besides LB film from surfactants depicted in Figure 1, similar monolayers can also be made from inorganic nanoparticles.

The Wilhelmy plate measurements give pressure – area isotherms that show phase transition-like behaviour of the LM films, as mentioned before (see figure below).

Moving into the solid region is accompanied by another sharp transition to a more severe area dependent pressure.

This trend continues up to a point where the molecules are relatively close packed and have very little room to move.

These films have different optical, electrical and biological properties which are composed of some specific organic compounds.

Organic compounds usually have more positive responses than inorganic materials for outside factors (pressure, temperature or gas change).