Lime kiln

Because it is so readily made by heating limestone, lime must have been known from the earliest times, and all the early civilizations used it in building mortars and as a stabilizer in mud renders and floors.

[3] According to finds at 'Ain Ghazal in Jordan, Yiftahel in Palestine[4], and Abu Hureyra in Syria dating to 7500–6000 BCE, the earliest use of lime was mostly as a binder on floors and in plaster for coating walls.

[7] The earliest descriptions of lime kilns differ little from those used for small-scale manufacture a century ago.

[citation needed] Because land transportation of minerals like limestone and coal was difficult in the pre-industrial era, they were distributed by sea, and lime was most often manufactured at small coastal ports.

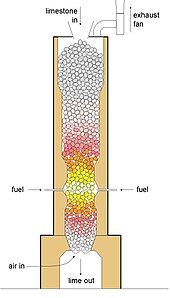

In a draw kiln, usually a stone structure, the chalk or limestone was layered with wood, coal or coke and lit.

[8][9] The common feature of early kilns was an egg-cup shaped burning chamber, with an air inlet at the base (the "eye"), constructed of brick.

Limestone was crushed (often by hand) to fairly uniform 20–60 mm (1–2+1⁄2 in) lumps – fine stone was rejected.

Successive dome-shaped layers of limestone and wood or coal were built up in the kiln on grate bars across the eye.

When loading was complete, the kiln was kindled at the bottom, and the fire gradually spread upwards through the charge.

Because there were large temperature differences between the center of the charge and the material close to the wall, a mixture of underburned (i.e. high loss on ignition), well-burned and dead-burned lime was normally produced.

One example at Annery in North Devon, England, near Great Torrington, was made up of three kilns grouped together in an 'L' shape and was situated beside the Torrington canal and the River Torridge to bring in the limestone and coal, and to transport away the calcined lime in the days before properly metalled roads existed.

The town, now called Walkerville, was set on an isolated part of the Victorian coastline and exported the lime by ship.

The development of the national rail network made the local small-scale kilns increasingly unprofitable, and they gradually died out through the 19th century.

The fresh feed fed in at the top is first dried then heated to 800 °C, where de-carbonation begins, and proceeds progressively faster as the temperature rises.

As with batch kilns, only large, graded stone can be used, in order to ensure uniform gas-flows through the charge.

Due to temperature peak at the burners up to 1200 °C in a shaft kiln conditions are ideal to produce medium and hard burned lime.

Due to these features the regenerative kilns are today mainstream technology under conditions of substantial fuel costs.

The early use of simple rotary kilns had the advantages that a much wider range of limestone size could be used, from fines upwards, and undesirable elements such as sulfur can be removed.

Modern installations partially overcome this disadvantage by adding a preheater, which has the same good solids/gas contact as a shaft kiln, but fuel consumption is still somewhat higher, typically in range of 4.5 to 6 MJ/kg.

Equipment is installed to trap this dust, typically in the form of electrostatic precipitators or bag filters.

Wainmans Double Arched Lime Kiln – Made Grade II Listed Building – 1 February 2005 Details & Image: https://web.archive.org/web/20140522012536/http://cowlingweb.co.uk/local_history/history/wainmanslimekiln.asp