Semi-empirical mass formula

It was first formulated in 1935 by German physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker,[2] and although refinements have been made to the coefficients over the years, the structure of the formula remains the same today.

The formula gives a good approximation for atomic masses and thereby other effects.

However, it fails to explain the existence of lines of greater binding energy at certain numbers of protons and neutrons.

The liquid-drop model was first proposed by George Gamow and further developed by Niels Bohr, John Archibald Wheeler and Lise Meitner.

[3] It treats the nucleus as a drop of incompressible fluid of very high density, held together by the nuclear force (a residual effect of the strong force), there is a similarity to the structure of a spherical liquid drop.

The corresponding mass formula is defined purely in terms of the numbers of protons and neutrons it contains.

The original Weizsäcker formula defines five terms: The mass of an atomic nucleus, for

The strong force affects both protons and neutrons, and as expected, this term is independent of Z.

Therefore, the number of pairs of particles that actually interact is roughly proportional to A, giving the volume term its form.

nucleons, with equal numbers of protons and neutrons, then the total kinetic energy is

This can also be thought of as a surface-tension term, and indeed a similar mechanism creates surface tension in liquids.

To a very rough approximation, the nucleus can be considered a sphere of uniform charge density.

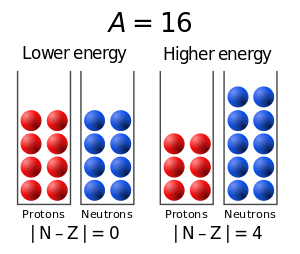

Protons and neutrons, being distinct types of particles, occupy different quantum states.

The actual form of the asymmetry term can again be derived by modeling the nucleus as a Fermi ball of protons and neutrons.

The discrepancy is explained by our model not being accurate: nucleons in fact interact with each other and are not spread evenly across the nucleus.

For example, in the shell model, a proton and a neutron with overlapping wavefunctions will have a greater strong interaction between them and stronger binding energy.

is found empirically to have a value of about 1000 keV, slowly decreasing with mass number A.

The binding energy may be increased by converting one of the odd protons or neutrons into a neutron or proton, so the odd nucleon can form a pair with its odd neighbour forming[clarification needed] and even Z, N. The pairs have overlapping wave functions and sit very close together with a bond stronger than any other configuration.

The dependence on mass number is commonly parametrized as The value of the exponent kP is determined from experimental binding-energy data.

In the past its value was often assumed to be −3/4, but modern experimental data indicate that a value of −1/2 is nearer the mark: Due to the Pauli exclusion principle the nucleus would have a lower energy if the number of protons with spin up were equal to the number of protons with spin down.

Only if both Z and N are even, can both protons and neutrons have equal numbers of spin-up and spin-down particles.

The Fermi-ball calculation we have used above, based on the liquid-drop model but neglecting interactions, will give an

This means that the actual effect for large nuclei will be larger than expected by that model.

For example, in the shell model, two protons with the same quantum numbers (other than spin) will have completely overlapping wavefunctions and will thus have greater strong interaction between them and stronger binding energy.

This makes it energetically favourable (i.e. having lower energy) for protons to form pairs of opposite spin.

Their values can vary depending on how they are fitted to the data and which unit is used to express the mass.

By maximizing Eb(A, Z) with respect to Z, one would find the best neutron–proton ratio N/Z for a given atomic weight A.

Maximizing Eb(A)/A with respect to A gives the nucleus which is most strongly bound, i.e. most stable.

It was originally speculated that elements beyond atomic number 104 could not exist, as they would undergo fission with very short half-lives,[12] though this formula did not consider stabilizing effects of closed nuclear shells.

A modified formula considering shell effects reproduces known data and the predicted island of stability (in which fission barriers and half-lives are expected to increase, reaching a maximum at the shell closures), though also suggests a possible limit to existence of superheavy nuclei beyond Z = 120 and N = 184.