Historiography of the United States

She emphasized the dangers to republicanism emanating from Britain, and called for the subordination of passion to reason, and the subsuming of private selfishness in the general public good.

[9] George Bancroft (1800–1891), trained in the leading German universities, was a Democratic politician and accomplished scholar, whose magisterial History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent covered the new nation in depth down to 1789.

Billias argues Bancroft played on four recurring themes to explain how America developed its unique values: providence, progress, patria, and pan-democracy.

[12] Bancroft was an indefatigable researcher who had a thorough command of the sources, but his rotund romantic style and enthusiastic patriotism annoyed later generations of scientific historians, who did not assign his books to students.

[16] The builders of state historical societies and archives in the late 19th and early 20th century were more than antiquarians—they had the mission of creating as well as preserving and disseminating the collective memories of their communities.

At the national level, major efforts to collect and publish important documents from the revolutionary era were undertaken by Jonathan Elliott (1784–1846), Jared Sparks (1789–1866), Peter Force (1790–1868) and other editors.

Schlesinger argued the false propaganda was effective: "The stigmatizing of British policy as 'tyranny,' 'oppression' and 'slavery, had little or no objective reality, at least prior to the Intolerable Acts but ceaseless repetition of the charge kept emotions at fever pitch.

Pocock explained the intellectual sources in America:[33] The Whig canon and the neo-Harringtonians, John Milton, James Harrington and Sidney, Trenchard, Gordon and Bolingbroke, together with the Greek, Roman, and Renaissance masters of the tradition as far as Montesquieu, formed the authoritative literature of this culture; and its values and concepts were those with which we have grown familiar: a civic and patriot ideal in which the personality was founded in property, perfected in citizenship but perpetually threatened by corruption; government figuring paradoxically as the principal source of corruption and operating through such means as patronage, faction, standing armies (opposed to the ideal of the militia); established churches (opposed to the Puritan and deist modes of American religion); and the promotion of a monied interest—though the formulation of this last concept was somewhat hindered by the keen desire for readily available paper credit common in colonies of settlement.Revolutionary Republicanism was centered on limiting corruption and greed.

[35] Since the 1980s a major trend has been to locate the colonial and revolutionary eras in the wider context of Atlantic history, with emphasis on the multiple interactions among the Americas, Europe and Africa.

Prominent Beardian historians included C. Vann Woodward, Howard K. Beale, Fred Harvey Harrington, Jackson Turner Main, and Richard Hofstadter (in his early years)[42] Similar to Beard in his economic interpretation, and almost as influential in the 1930s and 1940s was literary scholar Vernon Louis Parrington.

[43] Beard was famous as a political liberal, but he strenuously opposed American entry into World War II, for which he blamed Franklin D. Roosevelt more than Japan or Germany.

[46][47] To replace Beardianism "consensus" historiography emerged in the late 1940s and 1950s, with such leaders including Richard Hofstadter, Louis Hartz, Daniel J. Boorstin and David M. Potter.

Instead of persistent conflict (whether between agrarians and industrialists, capital and labor, or Democrats and Republicans), American history was characterize by broad agreement on fundamentals, particularly the virtues of individual liberty, private property, and capitalist enterprise.

From a professional standpoint, he argues, "American Indian history has a venerable past and boasts a tremendous volume of scholarship judging by the published bibliographies.

In academic history, Francis Jennings's The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (New York: Norton, 1975) was notable for strong attacks on the Puritans and rejection of traditional portrayal of the wars between the indigenous peoples and colonists.

Writing in 2005, the historian Eric Foner states: Their account of the era rested, as one member of the Dunning school put it, on the assumption of "negro incapacity."

Finding it impossible to believe that blacks could ever be independent actors on the stage of history, with their own aspirations and motivations, Dunning et al. portrayed African Americans either as "children", ignorant dupes manipulated by unscrupulous whites, or as savages, their primal passions unleashed by the end of slavery.

[58] In portraying the more benign version of slavery, they also argue in their 1974 book that the material conditions under which the slaves lived and worked compared favorably to those of free workers in the agriculture and industry of the time.

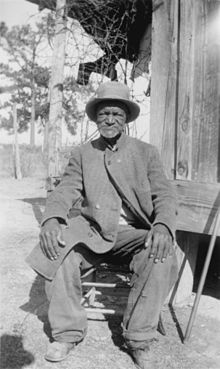

[59] Important work on slavery has continued; for instance, in 2003, Steven Hahn published the Pulitzer Prize-winning account, A Nation under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration, which examined how slaves built community and political understanding while enslaved, so they quickly began to form new associations and institutions when emancipated, including black churches separate from white control.

[61] Since the 1960s, the emphasis has been very largely on slavery as the cause of the Civil War, with the anti-slavery element in the North committed to blocking the expansion of the slave system because it violated the rights of free white farmers and workers.

Bailey argued Stalin violated promises he had made at Yalta, imposed Soviet-dominated regimes on unwilling Eastern European populations, and conspired to spread communism throughout the world.

[67] The seminal "post-revisionist" accounts are by John Lewis Gaddis, starting with his The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941–1947 (1972) and continuing through his study of George F. Kennan: An American Life (2011).

They reported that when all the men left for war, the women took command, found ersatz and substitute foods, rediscovered their old traditional skills with the spinning wheel when factory cloth became unavailable, and ran all the farm or plantation operations.

The male-dominated discipline saw its purview as relatively limited to the study of the evolution of politics, government, and the law, and emphasized research in official state documents, thus leaving little room for an examination of women's activities or lives.

Gerda Lerner's dissertation, published as The Grimke Sisters of South Carolina in 1967, and Aileen Kraditor's The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement (1965) are just two notable examples.

They also created around a dozen regional women's history organizations and conference groups of their own to support their scholarly work and build intellectual and professional networks.

Female Slaves in the Plantation South (1985), helped to open up analysis of race, slavery, abolitionism and feminism, as well as resistance, power, activism, and themes of violence, sexualities, and the body.

[92] The professional service and scholarship of Darlene Clark Hine, Rosalyn Terborg -Penn, and Nell Irvin Painter on African American women also broke important ground in the 1980s and 1990s.

A seminal, landmark book, it sparked interest in the 1960s and 1970s in quantitative methods, census sources, "bottom-up" history, and the measurement of upward social mobility by different ethnic groups.

[98] Rather than being strictly areas of geographical segmentation, spatial patterns and concepts of place reveal the struggles for power of various social groups, including gender, class, race, and ethnic identity.