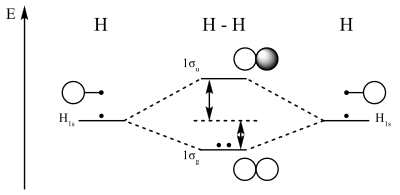

Molecular orbital diagram

For a diatomic molecule, an MO diagram effectively shows the energetics of the bond between the two atoms, whose AO unbonded energies are shown on the sides.

Often even for simple molecules, AO and MO levels of inner orbitals and their electrons may be omitted from a diagram for simplicity.

Atomic orbitals can also interact with each other out-of-phase which leads to destructive cancellation and no electron density between the two nuclei at the so-called nodal plane depicted as a perpendicular dashed line.

In this anti-bonding MO with energy much higher than the original AO's, any electrons present are located in lobes pointing away from the central internuclear axis.

The next step in constructing an MO diagram is filling the newly formed molecular orbitals with electrons.

Three general rules apply: The filled MO highest in energy is called the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the empty MO just above it is then the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO).

The resulting electron configuration can be described in terms of bond type, parity and occupancy for example dihydrogen 1σg2.

The relative order in MO energies and occupancy corresponds with electronic transitions found in photoelectron spectroscopy (PES).

Bands can resolve into fine structure with spacings corresponding to vibrational modes of the molecular cation (see Franck–Condon principle).

The starting point for any MO diagram is a predefined molecular geometry for the molecule in question.

For instance, in dioxygen the 3σg MO can be roughly considered to be formed from interaction of oxygen 2pz AOs only.

It is found to be lower in energy than the 1πu MO, both experimentally and from more sophisticated computational models, so that the expected order of filling is the 3σg before the 1πu.

[11] This can be rationalised as the first-approximation 3σg has a suitable symmetry to interact with the 2σg bonding MO formed from the 2s AOs.

For the aforementioned molecules this results in the 3σg being higher in energy than the 1πu MO, which is where s-p mixing is most evident.

The photoelectron spectrum of dihydrogen shows a single set of multiplets between 16 and 18 eV (electron volts).

However, by removing one electron from dihelium, the stable gas-phase species He+2 ion is formed with bond order 1/2.

[15] MO theory correctly predicts that dilithium is a stable[clarification needed] molecule with bond order 1 (configuration 1σg21σu22σg2).

Dilithium is a gas-phase molecule with a much lower bond strength than dihydrogen because the 2s electrons are further removed from the nucleus.

The resulting bonding orbital has its electron density in the shape of two lobes above and below the plane of the molecule.

Because the electrons have equal energy (they are degenerate) diboron is a diradical and since the spins are parallel the molecule is paramagnetic.

As in diboron, these two unpaired electrons have the same spin in the ground state, which is a paramagnetic diradical triplet oxygen.

The first excited state has both HOMO electrons paired in one orbital with opposite spins, and is known as singlet oxygen.

In heteronuclear diatomic molecules, mixing of atomic orbitals only occurs when the electronegativity values are similar.

Applying the LCAO-MO method allows us to move away from a more static Lewis structure type approach and actually account for periodic trends that influence electron movement.

A further understanding for the energy level refinement can be acquired by delving into quantum chemistry; the Schrödinger equation can be applied to predict movement and describe the state of the electrons in a molecule.

Carbon dioxide, CO2, is a linear molecule with a total of sixteen bonding electrons in its valence shell.

With these derived atomic orbitals, symmetry labels are deduced with respect to rotation about the principal axis which generates a phase change, pi bond (π)[26] or generates no phase change, known as a sigma bond (σ).

Significant atomic orbital overlap explains why sp bonding may occur.

For example, an orbital of B1 symmetry (called a b1 orbital with a small b since it is a one-electron function) is multiplied by -1 under the symmetry operations C2 (rotation about the 2-fold rotation axis) and σv'(yz) (reflection in the molecular plane).

It is multiplied by +1(unchanged) by the identity operation E and by σv(xz) (reflection in the plane bisecting the H-O-H angle).