Brain

Axons are usually myelinated and carry trains of rapid micro-electric signal pulses called action potentials to target specific recipient cells in other areas of the brain or distant parts of the body.

Some basic types of responsiveness such as reflexes can be mediated by the spinal cord or peripheral ganglia, but sophisticated purposeful control of behavior based on complex sensory input requires the information integrating capabilities of a centralized brain.

[20] There are several invertebrate species whose brains have been studied intensively because they have properties that make them convenient for experimental work: The first vertebrates appeared over 500 million years ago (Mya) during the Cambrian period, and may have resembled the modern jawless fish (hagfish and lamprey) in form.

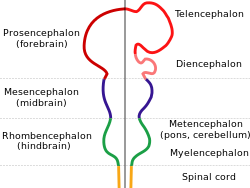

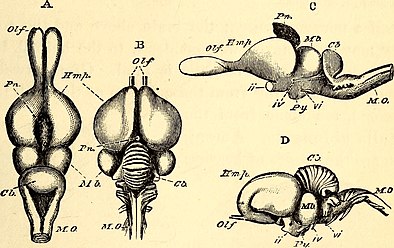

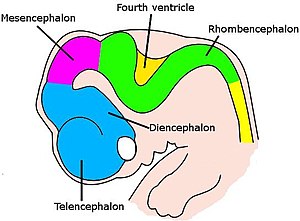

All of these brains contain the same set of basic anatomical structures, but many are rudimentary in the hagfish, whereas in mammals the foremost part (forebrain, especially the telencephalon) is greatly developed and expanded.

[36] As a result of the osmotic restriction by the blood-brain barrier, the metabolites within the brain are cleared mostly by bulk flow of the cerebrospinal fluid within the glymphatic system instead of via venules like other parts of the body.

[38] Here is a list of some of the most important vertebrate brain components, along with a brief description of their functions as currently understood: Modern reptiles and mammals diverged from a common ancestor around 320 million years ago.

[55][56][57] Vertebrates share the highest levels of similarities during embryological development, controlled by conserved transcription factors and signaling centers, including gene expression, morphological and cell type differentiation.

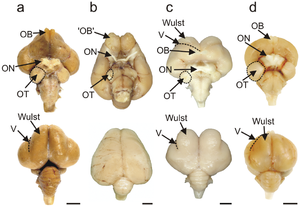

Birds possess large, complex brains, which process, integrate, and coordinate information received from the environment and make decisions on how to respond with the rest of the body.

[71] As the embryo transforms from a round blob of cells into a wormlike structure, a narrow strip of ectoderm running along the midline of the back is induced to become the neural plate, the precursor of the nervous system.

The result of this pathfinding process is that the growth cone navigates through the brain until it reaches its destination area, where other chemical cues cause it to begin generating synapses.

The retina, before birth, contains special mechanisms that cause it to generate waves of activity that originate spontaneously at a random point and then propagate slowly across the retinal layer.

The two areas for which adult neurogenesis is well established are the olfactory bulb, which is involved in the sense of smell, and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, where there is evidence that the new neurons play a role in storing newly acquired memories.

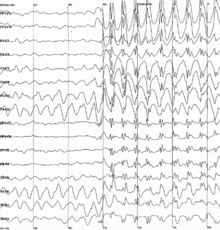

The electrical properties of neurons are controlled by a wide variety of biochemical and metabolic processes, most notably the interactions between neurotransmitters and receptors that take place at synapses.

Glial cells play a major role in brain metabolism by controlling the chemical composition of the fluid that surrounds neurons, including levels of ions and nutrients.

[8] A key component of the sleep system is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a tiny part of the hypothalamus located directly above the point at which the optic nerves from the two eyes cross.

The SCN continues to keep time even if it is excised from the brain and placed in a dish of warm nutrient solution, but it ordinarily receives input from the optic nerves, through the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT), that allows daily light-dark cycles to calibrate the clock.

In vertebrates, the part of the brain that plays the greatest role is the hypothalamus, a small region at the base of the forebrain whose size does not reflect its complexity or the importance of its function.

Already in the late 19th century theorists like Santiago Ramón y Cajal argued that the most plausible explanation is that learning and memory are expressed as changes in the synaptic connections between neurons.

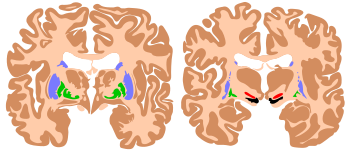

Even though it is protected by the skull and meninges, surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid, and isolated from the bloodstream by the blood–brain barrier, the delicate nature of the brain makes it vulnerable to numerous diseases and several types of damage.

In animal studies, most commonly involving rats, it is possible to use electrodes or locally injected chemicals to produce precise patterns of damage and then examine the consequences for behavior.

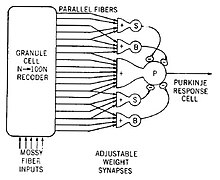

On the other hand, it is possible to study algorithms for neural computation by simulating, or mathematically analyzing, the operations of simplified "units" that have some of the properties of neurons but abstract out much of their biological complexity.

Recent years have seen increasing applications of genetic and genomic techniques to the study of the brain [129] and a focus on the roles of neurotrophic factors and physical activity in neuroplasticity.

... And by the same organ we become mad and delirious, and fears and terrors assail us, some by night, and some by day, and dreams and untimely wanderings, and cares that are not suitable, and ignorance of present circumstances, desuetude, and unskillfulness.

[132] Galen's ideas were widely known during the Middle Ages, but not much further progress came until the Renaissance, when detailed anatomical study resumed, combined with the theoretical speculations of René Descartes and those who followed him.

[132] The first real progress toward a modern understanding of nervous function, though, came from the investigations of Luigi Galvani (1737–1798), who discovered that a shock of static electricity applied to an exposed nerve of a dead frog could cause its leg to contract.

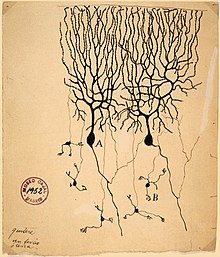

In the hands of Camillo Golgi, and especially of the Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the new stain revealed hundreds of distinct types of neurons, each with its own unique dendritic structure and pattern of connectivity.

Reflecting the new understanding, in 1942 Charles Sherrington visualized the workings of the brain waking from sleep: The great topmost sheet of the mass, that where hardly a light had twinkled or moved, becomes now a sparkling field of rhythmic flashing points with trains of traveling sparks hurrying hither and thither.

[139] Over the years, though, accumulating information about the electrical responses of brain cells recorded from behaving animals has steadily moved theoretical concepts in the direction of increasing realism.

[140] A few years later David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel discovered cells in the primary visual cortex of monkeys that become active when sharp edges move across specific points in the field of view—a discovery for which they won a Nobel Prize.

[142] Other investigations of brain areas unrelated to vision have revealed cells with a wide variety of response correlates, some related to memory, some to abstract types of cognition such as space.