Mannerism

[1] Mannerism encompasses a variety of approaches influenced by, and reacting to, the harmonious ideals associated with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Vasari,[2] and early Michelangelo.

Where High Renaissance art emphasizes proportion, balance, and ideal beauty, Mannerism exaggerates such qualities, often resulting in compositions that are asymmetrical or unnaturally elegant.

[3] Notable for its artificial (as opposed to naturalistic) qualities,[4] this artistic style privileges compositional tension and instability rather than the balance and clarity of earlier Renaissance painting.

It drove artists to look for new approaches and dramatically illuminated scenes, elaborate clothes and compositions, elongated proportions, highly stylized poses, and a lack of clear perspective.

[citation needed] The early Mannerists in Florence—especially the students of Andrea del Sarto such as Jacopo da Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino—are notable for elongated forms, precariously balanced poses, a collapsed perspective, irrational settings, and theatrical lighting.

[citation needed] In past analyses, it has been noted that mannerism arose in the early 16th century contemporaneously with a number of other social, scientific, religious and political movements such as the Copernican heliocentrism, the Sack of Rome in 1527, and the Protestant Reformation's increasing challenge to the power of the Catholic Church.

[22] This explanation for the radical stylistic shift c. 1520 has fallen out of scholarly favor, though early Mannerist art is still sharply contrasted with High Renaissance conventions; the accessibility and balance achieved by Raphael's School of Athens no longer seemed to interest young artists.

Subsequent mannerists stressed intellectual conceits and artistic virtuosity, features that have led later critics to accuse them of working in an unnatural and affected "manner" (maniera).

Based largely at courts and in intellectual circles around Europe, Maniera art couples exaggerated elegance with exquisite attention to surface and detail: porcelain-skinned figures recline in an even, tempered light, acknowledging the viewer with a cool glance, if they make eye contact at all.

[26] Other parts of Northern Europe did not have the advantage of such direct contact with Italian artists, but the Mannerist style made its presence felt through prints and illustrated books.

Walter Friedlaender identified this period as "anti-mannerism", just as the early Mannerists were "anti-classical" in their reaction away from the aesthetic values of the High Renaissance[21]: 14 and today the Carracci brothers and Caravaggio are agreed to have begun the transition to Baroque-style painting which was dominant by 1600.

Baccio Bandinelli took over the project of Hercules and Cacus from the master himself, but it was little more popular then than it is now, and maliciously compared by Benvenuto Cellini to "a sack of melons", though it had a long-lasting effect in apparently introducing relief panels on the pedestal of statues.

[28] Cellini's bronze Perseus with the Head of Medusa is certainly a masterpiece, designed with eight angles of view, another Mannerist characteristic, and artificially stylized in comparison with the Davids of Michelangelo and Donatello.

[30] Small bronze figures for collector's cabinets, often mythological subjects with nudes, were a popular Renaissance form at which Giambologna, originally Flemish but based in Florence, excelled in the later part of the century.

Lomazzo's systematic codification of aesthetics, which typifies the more formalized and academic approaches typical of the later 16th century, emphasized a consonance between the functions of interiors and the kinds of painted and sculpted decors that would be suitable.

His less practical and more metaphysical Idea del tempio della pittura (The ideal temple of painting, Milan, 1590) offers a description along the lines of the "four temperaments" theory of human nature and personality, defining the role of individuality in judgment and artistic invention.

A sense of tense, controlled emotion expressed in elaborate symbolism and allegory, and an ideal of female beauty characterized by elongated proportions are features of this style.

Specifically, within the Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time, Bronzino utilizes the tactics of Mannerist movement, attention to detail, color, and sculptural forms.

[5] Key aspects of Mannerism in El Greco include the jarring "acid" palette, elongated and tortured anatomy, irrational perspective and light, and obscure and troubling iconography.

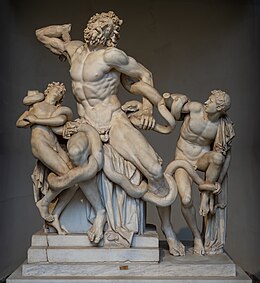

Painted in 1610,[42] it depicts the mythological tale of Laocoön, who warned the Trojans about the danger of the wooden horse which was presented by the Greeks as peace offering to the goddess Minerva.

Instead of being set against the backdrop of Troy, El Greco situated the scene near Toledo, Spain in order to "universalize the story by drawing out its relevance for the contemporary world.

In the portrait of Rudolf II, Arcimboldo also strays away from the naturalistic representation of the Renaissance, and explores the construction of composition by rendering him from a jumble of fruits, vegetables, plants and flowers.

It corresponds to the third and final stage of the Spanish Renaissance architecture, which evolved into a progressive purification ornamental, from the initial Plateresque to classical Purism of the second third of the 16th century and total nudity decorative that introduced the Herrerian style.

Dense with ornament of "Roman" detailing, the display doorway at Colditz Castle exemplifies the northern style, characteristically applied as an isolated "set piece" against unpretentious vernacular walling.

[64] Castagno's was the first study to define a theatrical form as Mannerist, employing the vocabulary of Mannerism and maniera to discuss the typification, exaggerated, and effetto meraviglioso of the comici dell'arte.

The study is largely iconographic, presenting a pictorial evidence that many of the artists who painted or printed commedia images were in fact, coming from the workshops of the day, heavily ensconced in the maniera tradition.

'dance of the buttocks') celebrates the commedia's blatant eroticism, with protruding phalli, spears posed with the anticipation of a comic ream, and grossly exaggerated masks that mix the bestial with human.

The eroticism of the innamorate ("lovers") including the baring of breasts, or excessive veiling, was quite in vogue in the paintings and engravings from the second School of Fontainebleau, particularly those that detect a Franco-Flemish influence.

Freed from the external rules, the actor celebrated the evanescence of the moment; much the way Benvenuto Cellini would dazzle his patrons by draping his sculptures, unveiling them with lighting effects and a sense of the marvelous.

In an interview, film director Peter Greenaway mentions Federico Fellini and Bill Viola as two major inspirations for his exhaustive and self-referential play with the insoluble tension between the database form of images and the various analogous and digital interfaces that structure them cinematically.