Glossary of ancient Roman religion

Macrobius[20] lists arbores felices (plural) as the oak (four species thereof), the birch, the hazelnut, the sorbus, the white fig, the pear, the apple, the grape, the plum, the cornus and the lotus.

"Taking the auspices" was an important part of all major official business, including inaugurations, senatorial debates, legislation, elections and war, and was held to be an ancient prerogative of Regal and patrician magistrates.

The right of observing the "greater auspices" was conferred on a Roman magistrate holding imperium, perhaps by a Lex curiata de imperio, although scholars are not agreed on the finer points of law.

On substantive grounds, a war required a "just cause," which might include rerum repetitio, retaliation against another people for pillaging, or a breach of or unilateral recession from a treaty; or necessity, as in the case of repelling an invasion.

At the traditional public rituals of ancient Rome, officiants prayed, sacrificed, offered libations, and practiced augury capite velato,[72] "with the head covered" by a fold of the toga drawn up from the back.

A fragment of the Twelve Tables reading si malum carmen incantassit ("if anyone should chant an evil spell") shows that it was a longstanding concern of Roman law to suppress malevolent magic.

Those who make a distinction hold that the libri were the secret archive containing rules and precepts of the ius sacrum (holy law), texts of spoken formulae, and instructions on how to perform ritual acts, while the commentarii were the responsa (opinions and arguments) and decreta (binding explications of doctrine) that were available for consultation.

The dies imperii was a recognition that succession during the Empire might take place irregularly through the death or overthrow of an emperor, in contrast to the annual magistracies of the Republic when the year was designated by the names of consuls serving their one-year term.

[156] Because of the rate of infant mortality, perhaps as high as 40 percent,[157] the newborn in its first few days of life was held as in a liminal phase, vulnerable to malignant forces (see List of Roman birth and childhood deities).

[164] As part of a flurry of religious reforms and restorations in the period from 38 BC to 17 AD, no fewer than fourteen temples had their dies natalis moved to another date, sometimes with the clear purpose of aligning them with new Imperial theology after the collapse of the Republic.

"[188] In The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, however, Émile Durkheim regarded the concept as not merely utilitarian, but an expression of "the mechanism of the sacrificial system itself" as "an exchange of mutually invigorating good deeds between the divinity and his faithful.

The ritual was conducted in a military setting either as a threat during a siege or as a result of surrender, and aimed at diverting the favor of a tutelary deity from the opposing city to the Roman side, customarily with a promise of a better-endowed cult or a more lavish temple.

When the deity's portion was cooked, it was sprinkled with mola salsa (ritually prepared salted flour) and wine, then placed in the fire on the altar for the offering; the technical verb for this action was porricere.

[296] Ovid says that the statue of Venus Verticordia was bathed as part of the Veneralia on the first of April, but the absence of this lavatio in any other source may indicate that since it was meant to be conducted by women, the magistrates did not attend.

Christian writers later developed a distinction between miracula, the true forms of which were evidence of divine power in the world, and mere mirabilia, things to be marveled at but not resulting from God's intervention.

Lucus is more strictly a sacred grove,[352] as defined by Servius as "a large number of trees with a religious significance",[353] and distinguished from the silva, a natural forest; saltus, territory that is wilderness; and a nemus, an arboretum that is not consecrated (but compare Celtic nemeton).

Legislation by Clodius as tribune of the plebs in 58 BC was aimed at ending the practice,[361] or at least curtailing its potential for abuse; obnuntiatio had been exploited the previous year as an obstructionist tactic by Julius Caesar's consular colleague Bibulus.

"[339] In his classic work on Roman divination, Auguste Bouché-Leclercq thus tried to distinguish theoretical usage of ostenta and portenta as applying to inanimate objects, monstra to biological signs, and prodigia for human acts or movements, but in non-technical writing the words tend to be used more loosely as synonyms.

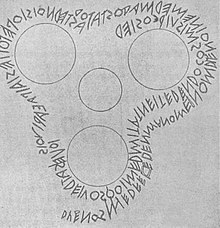

This explanation takes into account that the college was established by Sabine king Numa Pompilius and the institution is Italic: the expressions pontis and pomperias found in the Iguvine Tablets may denote a group or division of five or by five.

[400] The word could also refer in non-technical usage to an unnatural occurrence without specific religious significance; for instance, Pliny calls an Egyptian with a pair of non-functional eyes on the back of his head a portentum.

[402] In the schema of A. Bouché-Leclercq, portenta and ostenta are the two types of signs that appear in inanimate nature, as distinguished from the monstrum (a biological singularity), prodigia (the unique acts or movements of living beings), and a miraculum, a non-technical term that emphasizes the viewer's reaction.

Impure sacrifice and incorrect ritual were vitia (faults, hence "vice," the English derivative); excessive devotion, fearful grovelling to deities, and the improper use or seeking of divine knowledge were superstitio; neglecting the religiones owed to the traditional gods was atheism, a charge leveled during the Empire at Jews,[438] Christians, and Epicureans.

"[452] This original meaning of ritus may be compared to the concept of ṛtá ("visible order", in contrast to dhāman, dhārman) in Vedic religion, a conceptual pairing analogous to Latin fas and ius.

[480] During the Gallic siege of Rome, a member of the gens Fabia risked his life to carry out the sacra of his clan on the Quirinal Hill; the Gauls were so impressed by his courageous piety that they allowed him to pass through their lines.

Festus defined municipalia sacra as "those owned originally, before the granting of Roman citizenship; the pontiffs desired that the people continue to observe them and to practice them in the way (mos) they had been accustomed to from ancient times.

"[510] Gaius writes that a building dedicated to a god is sacrum, but a town's wall and gate are res sanctae because they belong "in some way" to divine law, while a graveyard is religiosus because it is relinquished to the di Manes.

[532] The Latin word derives from a Proto-Indo-European root meaning a libation of wine offered to the gods, as does the Greek verb spendoo and the noun spondai, spondas, and Hittite spant-.

[543] By the early 2nd century AD, religions of other peoples that were perceived as resistant to religious assimilation began to be labeled by some Latin authors as superstitio, including druidism, Judaism, and Christianity.

[545] Supplicationes are days of public prayer when the men, women, and children of Rome traveled in procession to religious sites around the city praying for divine aid in times of crisis.

[558] Earlier in the Roman legal system, the plaintiff had to state his claim within a narrowly defined set of fixed phrases (certa verba); in the Mid Republic, more flexible formulas allowed a more accurate description of the particulars of the issue under consideration.