Mark Antony

[9] According to the historian Plutarch, Antony spent his teenage years wandering through Rome with his brothers and friends gambling, drinking, and becoming involved in scandalous love affairs.

Years earlier in 63 BC, the Roman general Pompey had captured him and his father, King Aristobulus II, during his war against the declining Seleucid Empire.

Pharaoh Ptolemy XII Auletes had been deposed in a rebellion led by his daughter Berenice IV in 58 BC, forcing him to seek asylum in Rome.

In 60 BC, a secret agreement (known as the "First Triumvirate") was entered into between three men to control the Republic: Marcus Licinius Crassus, Gnaeus Pompey Magnus, and Gaius Julius Caesar.

Under the leadership of Cato and with the tacit support of Pompey, the senate passed a senatus consultum ultimum, a decree stripping Caesar of his command and ordering him to return to Rome and stand trial.

Meanwhile, Antony, with the rank of propraetor, was installed as governor of Italy and commander of the army, stationed there while Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, one of Caesar's staff officers, ran the provisional administration of Rome itself.

Antony opposed the law for political and personal reasons: he believed Caesar would not support such massive relief and suspected Dolabella had seduced his wife Antonia Hybrida.

Although Cassius was "the moving spirit" in the plot, winning over the chief assassins to the cause of tyrannicide, Brutus, with his family's history of deposing Rome's kings, became their leader.

Remaining in Cisalpine Gaul, Octavian dispatched emissaries to Rome in July 43 BC demanding he be appointed consul to succeed Hirtius and Pansa and that the senate rescind the decree declaring Antony a public enemy.

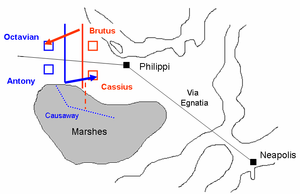

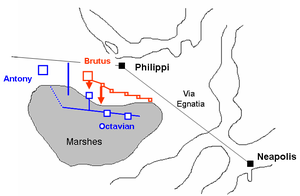

In the summer of 42 BC, Octavian and Antony sailed for Macedonia to face the liberatores with nineteen legions, the vast majority of their army[93] (approximately 100,000 regular infantry plus supporting cavalry and irregular auxiliary units), leaving Rome under the administration of Lepidus.

[94] The liberatores, who controlled Macedonia, did not wish to engage in a decisive battle, but rather to attain a good defensive position and then use their naval superiority to block the Triumvirs' communications with their supply base in Italy.

They had spent the previous months plundering Greek cities to swell their war-chest and had gathered in Thrace with the Roman legions from the Eastern provinces and levies from Rome's client kingdoms.

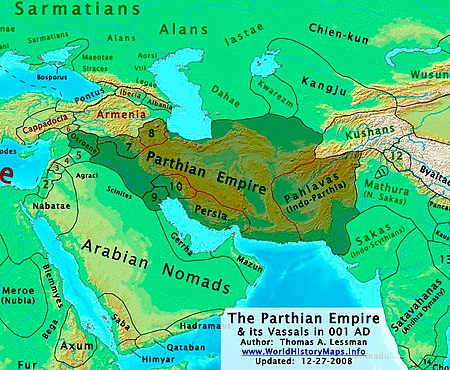

[100] As ruler of the East, Antony also assumed responsibility for overseeing Caesar's planned invasion of Parthia to avenge the defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC.

In Hasmonean Judea, several Israelite delegations complained to Antony of the harsh rule of Phasael and Herod, the sons of Rome's assassinated chief minister in the territory of Judaea, who was an Edomite called Antipater the Idumaean.

At Cleopatra's request, Antony ordered the execution of Arsinoe, who, though marched in Caesar's triumphal parade in 46 BC,[104] had been granted sanctuary at the temple of Artemis in Ephesus.

While Octavian pardoned Lucius for his role in the war and even granted him command in Spain as his chief lieutenant there, Fulvia was forced to flee to Greece with her children.

His reasons were to punish the Parthians for assisting Pompey in the recent civil war, to avenge Crassus' defeat at Carrhae, and especially to match the glory of Alexander the Great for himself.

[125][126] Despite Rome's internal turmoil during the time, the Parthians did not immediately benefit from the power vacuum in the East due to Orodes II's reluctance despite Labienus' urgings to the contrary.

The joint Parthian–Roman force, after initial success in Syria, separated to lead their offensive in two directions: Pacorus marched south toward Hasmonean Judea while Labienus crossed the Taurus Mountains to the north into Cilicia.

Though he left Alexandria for Tyre in early 40 BC, when he learned of the civil war between his wife and Octavian, he was forced to return to Italy with his army to secure his position in Rome rather than defeat the Parthians.

Ventidius' actions temporarily halted the Parthian advance and restored Roman authority in the East, forcing Pacorus to abandon his conquests and return to Parthia.

[132][133] Ventidius feared Antony's wrath if he invaded Parthian territory, thereby stealing his glory; so instead he attacked and subdued the eastern kingdoms, which had revolted against Roman control following the disastrous defeat of Crassus at Carrhae.

[135] While Octavian wanted an end to the ongoing blockade of Italy, Antony sought peace in the West in order to make the Triumvirate's legions available for his service in his planned campaign against the Parthians.

With this military purpose on his mind, Antony sailed to Greece with Octavia, where he behaved in a most extravagant manner, assuming the attributes of the Greek god Dionysus in 39 BC.

With Publius Ventidius Bassus returned to Rome in triumph for his defensive campaign against the Parthians, Antony appointed Gaius Sosius as the new governor of Syria and Cilicia in early 38 BC.

Antony, still in the West negotiating with Octavian, ordered Sosius to depose Antigonus, who had been installed in the recent Parthian invasion as the ruler of Hasmonean Judea, and to make Herod the new Roman client king in the region.

In addition to significant financial resources, Cleopatra's backing of his Parthian campaign allowed Antony to amass the largest army Rome had ever assembled in the East.

However, following Marcus Licinius Crassus's defeat at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, Armenia was forced into an alliance with Parthia due to Rome's weakened position in the East.

He distributed kingdoms among his children: Alexander Helios was named king of Armenia, Media and Parthia (territories which were not for the most part under the control of Rome), his twin Cleopatra Selene got Cyrenaica and Libya, and the young Ptolemy Philadelphus was awarded Syria and Cilicia.

Octavian responded with treason charges: of illegally keeping provinces that should be given to other men by lots, as was Rome's tradition, and of starting wars against foreign nations (Armenia and Parthia) without the consent of the senate.