Marine primary production

Marine primary production is the chemical synthesis in the ocean of organic compounds from atmospheric or dissolved carbon dioxide.

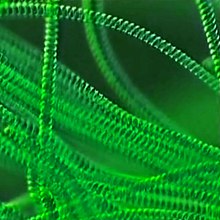

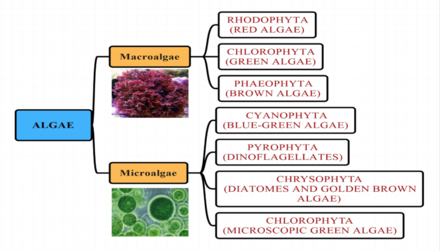

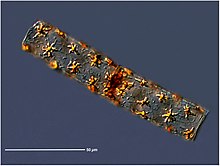

Marine algae includes the largely invisible and often unicellular microalgae, which together with cyanobacteria form the ocean phytoplankton, as well as the larger, more visible and complex multicellular macroalgae commonly called seaweed.

Some marine primary producers are specialised bacteria and archaea which are chemotrophs, making their own food by gathering around hydrothermal vents and cold seeps and using chemosynthesis.

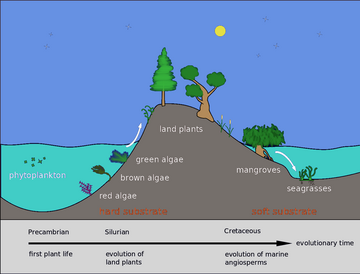

[5] In a reversal of the pattern on land, in the oceans, almost all photosynthesis is performed by algae and cyanobacteria, with a small fraction contributed by vascular plants and other groups.

Unlike terrestrial ecosystems, the majority of primary production in the ocean is performed by free-living microscopic organisms called phytoplankton.

However, the availability of light, the source of energy for photosynthesis, and mineral nutrients, the building blocks for new growth, play crucial roles in regulating primary production in the ocean.

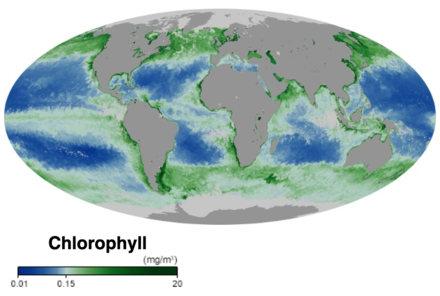

[10] In 2020 researchers reported that measurements over the last two decades of primary production in the Arctic Ocean show an increase of nearly 60% due to higher concentrations of phytoplankton.

Because oxygen was toxic to most life on Earth at the time, this led to the near-extinction of oxygen-intolerant organisms, a dramatic change which redirected the evolution of the major animal and plant species.

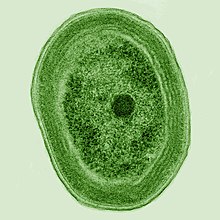

Chloroplasts (from the Greek chloros for green, and plastes for "the one who forms"[31]) are organelles that conduct photosynthesis, where the photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in the energy-storage molecules while freeing oxygen from water in plant and algal cells.

Despite this, chloroplasts can be found in an extremely wide set of organisms, some not even directly related to each other—a consequence of many secondary and even tertiary endosymbiotic events.

The significance of chlorophyll in converting light energy has been written about for decades, but phototrophy based on retinal pigments is just beginning to be studied.

[35] In 2000 a team of microbiologists led by Edward DeLong made a crucial discovery in the understanding of the marine carbon and energy cycles.

"The findings break from the traditional interpretation of marine ecology found in textbooks, which states that nearly all sunlight in the ocean is captured by chlorophyll in algae.

[44][45] Algae is an informal term for a widespread and diverse collection of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms which are not necessarily closely related and are thus polyphyletic.

Coccolithophores are of interest to those studying global climate change because as ocean acidity increases, their coccoliths may become even more important as a carbon sink.

Recent developments in molecular sequencing have allowed for the recovery of genomes directly from environmental samples and avoiding the need for culturing.

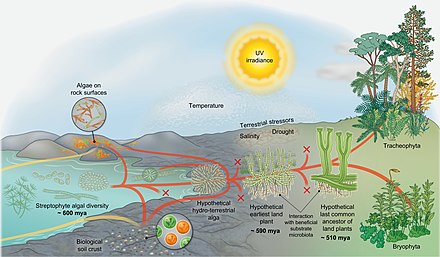

Furthermore, the earliest land plants had to successfully overcome a barrage of terrestrial stressors (including ultraviolet light and photosynthetically active irradiance, drought, drastic temperature shifts, etc.).

[69] During the course of evolution, some members of the populations of the earliest land plants gained traits that are adaptive in terrestrial environments (such as some form of water conductance, stomata-like structures, embryos, etc.

[79]: 160–163 Mangroves provide important nursery habitats for marine life, acting as hiding and foraging places for larval and juvenile forms of larger fish and invertebrates.

Based on satellite data, the total world area of mangrove forests was estimated in 2010 as 134,257 square kilometres (51,837 sq mi).

The total world area of seagrass meadows is more difficult to determine than mangrove forests, but was conservatively estimated in 2003 as 177,000 square kilometres (68,000 sq mi).

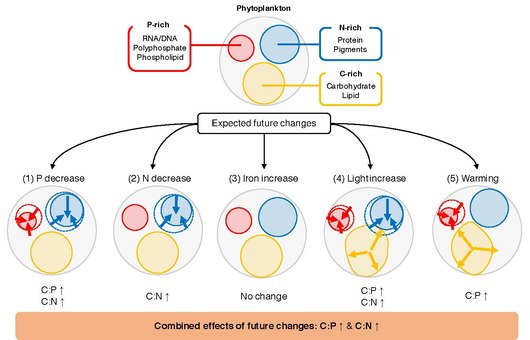

Phytoplankton grows in the upper light-lit layer of the ocean, where the amount of inorganic nutrients, light, and temperature vary spatially and temporally.

[84] Laboratory studies show that these fluctuations trigger responses at the cellular level, whereby cells modify resource allocation in order to adapt optimally to their ambient environment.

[93] Under a typical future warming scenario, the global ocean is expected to undergo changes in nutrient availability, temperature, and irradiance.

[84] Individual studies employ different sets of statistical analyses to characterize the effects of the environmental driver(s) on elemental ratios, ranging from a simple t test to more complex mixed models, which makes interstudy comparisons challenging.

In addition, since environmentally induced trait changes are driven by a combination of plasticity (acclimation), adaptation, and life history,[98][99] stoichiometric responses of phytoplankton can be variable even amongst closely related species.

[84] Meta-analysis/systematic review is a powerful statistical framework for synthesizing and integrating research results obtained from independent studies and for uncovering general trends.

[100] The seminal synthesis by Geider and La Roche in 2002,[101] as well as the more recent work by Persson et al. in 2010,[102] has shown that C:P and N:P could vary by up to a factor of 20 between nutrient-replete and nutrient-limited cells.

Most recently, Moreno and Martiny (2018) provided a comprehensive summary of how environmental conditions regulate cellular stoichiometry from a physiological perspective.

The results show that eukaryotic phytoplankton are more sensitive to the changes in macronutrients compared to prokaryotes, possibly due to their larger cell size and their abilities to regulate their gene expression patterns quickly.

click to animate

• Red = diatoms (big phytoplankton, which need silica)

• Yellow = flagellates (other big phytoplankton)

• Green = prochlorococcus (small phytoplankton that cannot use nitrate)

• Cyan = synechococcus (other small phytoplankton)

Opacity indicates concentration of the carbon biomass. In particular, the role of the swirls and filaments ( mesoscale features) appear important in maintaining high biodiversity in the ocean. [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

(2) it changes its configuration so a proton is expelled from the cell

(3) the chemical potential causes the proton to flow back to the cell

(4) thus generating energy

(5) in the form of adenosine triphosphate . [ 34 ]

An evolutionary scenario for the conquest of land by streptophytes [ 69 ]

Dating is roughly based on Morris et al. 2018. [ 70 ]

to major environmental drivers