Mass

Mass can be experimentally defined as a measure of the body's inertia, meaning the resistance to acceleration (change of velocity) when a net force is applied.

In the Standard Model of physics, the mass of elementary particles is believed to be a result of their coupling with the Higgs boson in what is known as the Brout–Englert–Higgs mechanism.

Although some theorists have speculated that some of these phenomena could be independent of each other,[3] current experiments have found no difference in results regardless of how it is measured: The mass of an object determines its acceleration in the presence of an applied force.

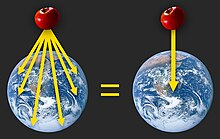

[note 1] Repeated experiments since the 17th century have demonstrated that inertial and gravitational mass are identical; since 1915, this observation has been incorporated a priori in the equivalence principle of general relativity.

However, because precise measurement of a cubic decimetre of water at the specified temperature and pressure was difficult, in 1889 the kilogram was redefined as the mass of a metal object, and thus became independent of the metre and the properties of water, this being a copper prototype of the grave in 1793, the platinum Kilogramme des Archives in 1799, and the platinum–iridium International Prototype of the Kilogram (IPK) in 1889.

[4] The new definition uses only invariant quantities of nature: the speed of light, the caesium hyperfine frequency, the Planck constant and the elementary charge.

The diverse magnitudes of units having the same name, which still appear today in our dry and liquid measures, could have arisen from the various commodities traded.

The larger avoirdupois pound for goods of commerce might have been based on volume of water which has a higher bulk density than grain.

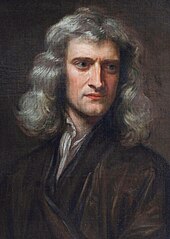

Albert Einstein developed his general theory of relativity starting with the assumption that the inertial and passive gravitational masses are the same.

The first experiments demonstrating the universality of free-fall were—according to scientific 'folklore'—conducted by Galileo obtained by dropping objects from the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

This is most likely apocryphal: he is more likely to have performed his experiments with balls rolling down nearly frictionless inclined planes to slow the motion and increase the timing accuracy.

This can easily be done in a high school laboratory by dropping the objects in transparent tubes that have the air removed with a vacuum pump.

The Roman pound and ounce were both defined in terms of different sized collections of the same common mass standard, the carob seed.

Using Brahe's precise observations of the planet Mars, Kepler spent the next five years developing his own method for characterizing planetary motion.

These four objects (later named the Galilean moons in honor of their discoverer) were the first celestial bodies observed to orbit something other than the Earth or Sun.

Galileo continued to observe these moons over the next eighteen months, and by the middle of 1611, he had obtained remarkably accurate estimates for their periods.

Sometime prior to 1638, Galileo turned his attention to the phenomenon of objects in free fall, attempting to characterize these motions.

However, Galileo's reliance on scientific experimentation to establish physical principles would have a profound effect on future generations of scientists.

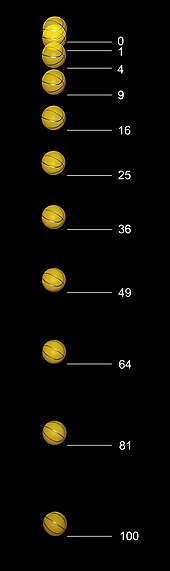

The time was measured using a water clock described as follows: Galileo found that for an object in free fall, the distance that the object has fallen is always proportional to the square of the elapsed time: Galileo had shown that objects in free fall under the influence of the Earth's gravitational field have a constant acceleration, and Galileo's contemporary, Johannes Kepler, had shown that the planets follow elliptical paths under the influence of the Sun's gravitational mass.

According to K. M. Browne: "Kepler formed a [distinct] concept of mass ('amount of matter' (copia materiae)), but called it 'weight' as did everyone at that time.

[15] In correspondence with Isaac Newton from 1679 and 1680, Hooke conjectured that gravitational forces might decrease according to the double of the distance between the two bodies.

Isaac Newton kept quiet about his discoveries until 1684, at which time he told a friend, Edmond Halley, that he had solved the problem of gravitational orbits, but had misplaced the solution in his office.

In November 1684, Isaac Newton sent a document to Edmund Halley, now lost but presumed to have been titled De motu corporum in gyrum (Latin for "On the motion of bodies in an orbit").

Newton later recorded his ideas in a three-book set, entitled Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (English: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy).

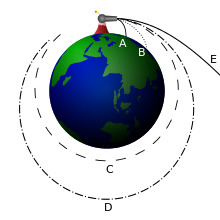

[20] Newton's cannonball was a thought experiment used to bridge the gap between Galileo's gravitational acceleration and Kepler's elliptical orbits.

However, Newton explains that when a stone is thrown horizontally (meaning sideways or perpendicular to Earth's gravity) it follows a curved path.

Hence, it should be theoretically possible to determine the exact number of carob seeds that would be required to produce a gravitational field similar to that of the Earth or Sun.

[22] (In practice, this "amount of matter" definition is adequate for most of classical mechanics, and sometimes remains in use in basic education, if the priority is to teach the difference between mass from weight.

[38][43] Under no circumstances do any excitations ever propagate faster than light in such theories—the presence or absence of a tachyonic mass has no effect whatsoever on the maximum velocity of signals (there is no violation of causality).

[44] While the field may have imaginary mass, any physical particles do not; the "imaginary mass" shows that the system becomes unstable, and sheds the instability by undergoing a type of phase transition called tachyon condensation (closely related to second order phase transitions) that results in symmetry breaking in current models of particle physics.