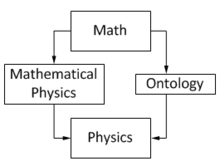

Mathematical physics

Nonrelativistic quantum mechanics includes Schrödinger operators, and it has connections to atomic and molecular physics.

This was, however, gradually supplemented by topology and functional analysis in the mathematical description of cosmological as well as quantum field theory phenomena.

In the mathematical description of these physical areas, some concepts in homological algebra and category theory[3] are also important.

Because of the required level of mathematical rigour, these researchers often deal with questions that theoretical physicists have considered to be already solved.

In the first decade of the 16th century, amateur astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus proposed heliocentrism, and published a treatise on it in 1543.

Galileo's 1638 book Discourse on Two New Sciences established the law of equal free fall as well as the principles of inertial motion, two central concepts of what today is known as classical mechanics.

[11] Christiaan Huygens, a talented mathematician and physicist and older contemporary of Newton, was the first to successfully idealize a physical problem by a set of mathematical parameters in Horologium Oscillatorum (1673), and the first to fully mathematize a mechanistic explanation of an unobservable physical phenomenon in Traité de la Lumière (1690).

[12][13] The prevailing framework for science in the 16th and early 17th centuries was one borrowed from Ancient Greek mathematics, where geometrical shapes formed the building blocks to describe and think about space, and time was often thought as a separate entity.

With the introduction of algebra into geometry, and with it the idea of a coordinate system, time and space could now be thought as axes belonging to the same plane.

By the middle of the 17th century, important concepts such as the fundamental theorem of calculus (proved in 1668 by Scottish mathematician James Gregory) and finding extrema and minima of functions via differentiation using Fermat's theorem (by French mathematician Pierre de Fermat) were already known before Leibniz and Newton.

The French Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827) made paramount contributions to mathematical astronomy, potential theory.

In Germany, Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) made key contributions to the theoretical foundations of electricity, magnetism, mechanics, and fluid dynamics.

The Irishmen William Rowan Hamilton (1805–1865), George Gabriel Stokes (1819–1903) and Lord Kelvin (1824–1907) produced several major works: Stokes was a leader in optics and fluid dynamics; Kelvin made substantial discoveries in thermodynamics; Hamilton did notable work on analytical mechanics, discovering a new and powerful approach nowadays known as Hamiltonian mechanics.

Very relevant contributions to this approach are due to his German colleague mathematician Carl Gustav Jacobi (1804–1851) in particular referring to canonical transformations.

The German Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) made substantial contributions in the fields of electromagnetism, waves, fluids, and sound.

The Galilean transformation had been the mathematical process used to translate the positions in one reference frame to predictions of positions in another reference frame, all plotted on Cartesian coordinates, but this process was replaced by Lorentz transformation, modeled by the Dutch Hendrik Lorentz [1853–1928].

It was hypothesized that the aether thus kept Maxwell's electromagnetic field aligned with the principle of Galilean invariance across all inertial frames of reference, while Newton's theory of motion was spared.

Austrian theoretical physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach criticized Newton's postulated absolute space.

In 1908, Einstein's former mathematics professor Hermann Minkowski, applied the curved geometry construction to model 3D space together with the 1D axis of time by treating the temporal axis like a fourth spatial dimension—altogether 4D spacetime—and declared the imminent demise of the separation of space and time.

General relativity replaces Cartesian coordinates with Gaussian coordinates, and replaces Newton's claimed empty yet Euclidean space traversed instantly by Newton's vector of hypothetical gravitational force—an instant action at a distance—with a gravitational field.

The gravitational field is Minkowski spacetime itself, the 4D topology of Einstein aether modeled on a Lorentzian manifold that "curves" geometrically, according to the Riemann curvature tensor.

Another revolutionary development of the 20th century was quantum theory, which emerged from the seminal contributions of Max Planck (1856–1947) (on black-body radiation) and Einstein's work on the photoelectric effect.

The development of early quantum physics followed by a heuristic framework devised by Arnold Sommerfeld (1868–1951) and Niels Bohr (1885–1962), but this was soon replaced by the quantum mechanics developed by Max Born (1882–1970), Louis de Broglie (1892–1987), Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976), Paul Dirac (1902–1984), Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961), Satyendra Nath Bose (1894–1974), and Wolfgang Pauli (1900–1958).

This revolutionary theoretical framework is based on a probabilistic interpretation of states, and evolution and measurements in terms of self-adjoint operators on an infinite-dimensional vector space.

Paul Dirac used algebraic constructions to produce a relativistic model for the electron, predicting its magnetic moment and the existence of its antiparticle, the positron.