Matilda of Tuscany

In this extensive conflict with the emerging reform Papacy over the relationship between spiritual (sacerdotium) and secular (regnum) power, Pope Gregory VII dismissed and excommunicated the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV in 1076.

The struggle between regnum and sacerdotium changed the social and rulership structure of the Italian cities permanently, giving them space for emancipation from foreign rule and communal development.

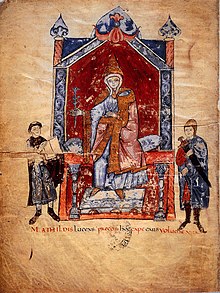

The account of Donizo reports that between 6 and 11 May 1111, Matilda was crowned Imperial Vicar and Vice-Queen of Italy by Henry V at Bianello Castle (Quattro Castella, Reggio Emilia).

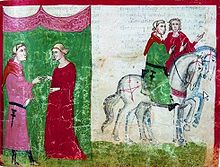

The rule of Matilda and her influence became identified as a cultural epoch in Italy that found expression in the flowering of numerous artistic, musical, and literary designs and miracle stories and legends.

The founded monasteries (Brescello, Polirone, Santa Maria di Felonica) were established in places of transport and strategic importance for the administrative consolidation of their large estates.

[9][10] According to the marital agreements, Beatrice brought important assets in Lorraine: the Château of Briey, the Lordships of Stenay, Mouzay, Juvigny, Longlier, and Orval that constituted the northern part of her paternal family's ancestral lands.

[20] Emperor Henry III was enraged by his cousin Beatrice's unauthorised union with his most vigorous adversary and took the opportunity to have her arrested, along with Matilda, when he marched south to attend a synod in Florence on Pentecost in 1055.

By the time she and her mother returned to Italy, in the company of Pope Victor II, Matilda was formally acknowledged as sole heiress to the greatest territorial lordship in the southern part of the Empire.

[29] Possibly taking advantage of the minority of Henry IV, Beatrice and Godfrey the Bearded wanted to consolidate the connection between the Houses of Lorraine and of Canossa in the long term by marrying their two children.

[34][35] In 1071, Beatrice had donated property to the Abbey of Frassinoro for the salvation of her granddaughter's soul and she granted twelve farms "for the health and life of my beloved daughter Matilda" (pro incolomitate et anima Matilde dilecte filie mee).

German chroniclers, writing of the synod held at Worms in January 1076, even suggested that Godfrey the Hunchback inspired an allegation by Henry IV of a licentious affair between Gregory VII and Matilda.

Beatrice started preparing Matilda for rule as head of the House of Canossa by holding court jointly with her [32] and, eventually, encouraging her to issue charters under her own authority as countess (comitissa) and duchess (ducatrix).

On 27 August 1077 Matilda donated her town of Scanello and other estates to the extent of 600 mansus near the court to Bishop Landulf and the chapter of Pisa Cathedral as a soul device (Seelgerät) for her and her parents.

[52] In view of the minority of Henry IV and close cooperation with the reform papacy, a lending under imperial law was of secondary importance for the House of Canossa Between 1076 and 1080, Matilda travelled to Lorraine to lay claim to her husband's estate in Verdun, which he had willed (along with the rest of his patrimony) to his nephew Godfrey of Bouillon, the son of his sister Ida.

The allegations included Gregory VII's election (which was described as illegitimate), the government of the Church through a "women's senate", and that "he shared a table with a strange woman and housed her, more familiar than necessary."

[51] These measures had a tremendous effect on contemporaries, as the words of the chronicler Bonizo of Sutri show: "When the news of the banishment of the king reached the ears of the people, our whole world trembled".

In Brixen on 25 June 1080, seven German, one Burgundian, and 20 Italian bishops decided to depose Gregory VII and nominated Archbishop Guibert of Ravenna as pope, who took the name of Clement III.

[73] In July 1081 at a synod in Lucca, Henry IV—on account of her 1079 donation to the Church—imposed Imperial ban upon Matilda and all her domains were forfeit, although this was not enough to eliminate her as a source of trouble, for she retained substantial allodial holdings.

[86] In 1094 Henry IV's second wife, the Rurikid princess Eupraxia of Kiev (renamed Adelaide after her marriage), escaped from her imprisonment at the monastery of San Zeno and spread serious allegations against him.

In 1089 Matilda (in her early forties) married Welf V, heir to the Duchy of Bavaria and who was probably fifteen to seventeen years old,[94] but none of the contemporary sources goes into the great age difference.

[45] Matilda's motive for this marriage, despite the large age difference and the political alliance—her new husband was a member of the Welf dynasty, who were important supporters of the papacy from the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries in their conflict with the German emperors (see Guelphs and Ghibellines)—, may also have been the hope for offspring:[97] late pregnancy was quite possible, as the example of Constance of Sicily shows.

[109][110] Mantua had to make considerable concessions in June 1090; the inhabitants of the city and the suburbs were freed from all "unjustified" oppression and all rights and property in Sacca, Sustante and Corte Carpaneta were confirmed.

[134] In an analysis of the documentary mentions, however, Gundula Grebner came to the conclusion that this scholar should not be classified in the circle of Matilda, but in that of Henry V.[135] Until well into the fourteenth century, medieval rule was exercised through itinerant court practice.

She could no longer have children of her own, and apparently for this reason she adopted Guido Guerra, member of the Guidi family, who were one of her main supporters in Florence (although in a genealogically strictly way, the Margravine's feudal heirs were the House of Savoy, descendants of Prangarda of Canossa, Matilda's paternal great-aunt).

[204] This agreement has been undisputedly interpreted in German historical studies since Wilhelm von Giesebrecht as an inheritance treaty, while Italian historians such as Luigi Simeoni and Werner Goez repeatedly questioned this.

[188][205][206] Elke Goez, on the other hand, assumed a mutual agreement with benefits from both sides: Matilda, whose health was weakened, probably waived her further support for Pope Paschal II with a view to a good understanding with the emperor.

[188][208] Some researchers see in the agreement with Henry V a turning away from the ideals of the so-called Gregorian reform, but Enrico Spagnesi emphasizes that Matilda had by no means given up her church reform-minded policy.

A memorial tomb for Matilda, commissioned by Pope Urban VIII and designed by Gianlorenzo Bernini with the statues being created by sculptor Andrea Bolgi, marks her burial place in St. Peter's and is often called the Honor and Glory of Italy.

[251] Since 1955 the Corteo Storico Matildico in Bianello Castle has been a reminiscent display of Matilda's meeting with Henry V and reported coronation as vicar and vice-queen; the event has taken place every year since then, usually on the last Sunday of May.

Matilda is a featured figure on Judy Chicago's installation piece The Dinner Party, being represented as one of the 999 names on the Heritage Floor, along some other contemporaries like her second cousin Adelaide of Susa.