Mataram kingdom

[8]: 108 Hostility between them did not end until 1016 when the Shailendra clan based in Srivijaya incited a rebellion by Wurawari, a vassal of the Mataram kingdom, and sacked the capital of Watugaluh in East Java.

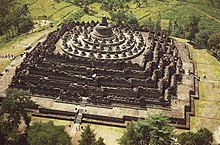

[8]: 130 [8]: 144–147 In the early 19th century, the discovery of numerous ruins of great monuments—such as Borobudur, Sewu and Prambanan—which dominated the landscape of the Kedu and Kewu plains in Yogyakarta and Central Java, caught the attention of some historians and scholars in the colonial Dutch East Indies.

[13] In the inscription it is referred to as kaḍatwan śrī mahārāja i bhūmi i mātaram, a phrase which means "Maharaja's kingdom in Mataram", as a form of mother personification which symbolises life, nature and the environment.

[14] The name of the Mataram kingdom was known during the reign of Sanjaya (narapati rāja śrī sañjaya)[15] which states in the Canggal inscription, dated from 654 Śaka or 732 AD, that he ruled in Java island (āsīddvīpavaraṁ yavākhyam).

The name of the Mataram kingdom was first discovered by epigraphy in Wuatan Tija inscription 802 Śaka or 880 AD (dewatā prasiddha maṅrakṣa kaḍatwan śrī mahārāja i bhūmi i mātaram kita).

This inscription, written in Sanskrit using the Pallava script, tells of the erection of a lingga (a symbol of Shiva) on the hill in the Kunjarakunja area, located on a noble island called Yawadwipa (Java) which had an abundance of rice and gold.

This period witnessed the blossoming of Javanese art and architecture, as numbers of majestic temples and monuments were erected and dominated the skyline of Kedu and Kewu Plain.

[5][6][7] In 851 an Arabic merchant named Sulaimaan recorded an event about Javanese Sailendras staging a surprise attack on the Khmers by approaching the capital from the river, after a sea crossing from Java.

[8]: 92 Unlike his predecessor the expansive warlike Dharanindra, Samaragrawira seems to be a pacifist, enjoying a peaceful prosperity of interior Java in Kedu Plain, and more interested on completing the Borobudur project.

This decision was proven as a mistake, as Jayavarman later revolted, moved his capital further inland north from Tonle Sap to Mahendraparvata, severed the link and proclaimed Cambodian independence from Java in 802.

After the short reign of Jebang, lord of Watu Humalang (r. 894–898), Balitung emerged as the leading contender for the throne of Java, and reunited the kingdom for the first time since Lokapāla's death.

He centralised royal authority and restricted the autonomy of aristocrats, supported both Hindu and Buddhist foundations, and for the first time, incorporated parts of east Java into the Mataram kingdom.

Balitung's motivations in producing these two edicts has elicited various hypotheses from historians, with some suggesting that he came to the throne in an irregular fashion and was therefore seeking legitimacy of his rule by calling upon his illustrious precursors.

However, no primary source gives us any explicit information about Balitung's position in the Mataram royal dynasty, so all theories about his familiar relations to earlier and later kings are purely hypothetical.

[71] The Kauthara Nha Trang temple of Po Nagar was ruined when ferocious, pitiless, dark-skinned men born in other countries, whose food was more horrible than corpses, and who were vicious and furious, came in ships .

Despite its fertility, ideal for rice agricultural kingdom, the Mataram Plain is quite isolated, its northern borders are protected by natural barrier of Merapi, Merbabu, Sumbing, Sundoro, Dieng and Ungaran volcanoes.

The complex stratified ancient Javan society, with its refined aesthetic taste in art and culture, is evidenced through the various scenes in narrative bas-reliefs carved on various temples dated from the Mataram era.

During this period the common concept of city, as it known in Europe, Middle East or China, as the urban concentration centre of politics, administration, religious and economic activities, was not quite established yet in ancient Java.

The capital itself is more likely refer to the palace, a walled compound called pura in Sanskrit, or in local Javanese as karaton or kadatwan, this is where the king and his family reside and rule his court.

Later expert suggests that the area in Secang, on the upper Progo river valley in northern Magelang Regency—with relatively high temple density—was possibly the secondary political centre of the kingdom.

The common people of mostly made a living in agriculture, especially as rice farmers, however, some may have pursued other careers, such as hunter, trader, artisan, weaponsmith, sailor, soldier, dancer, musician, food or drink vendor, etc.

Exploiting the fertile volcanic soil of Central Java and the intensive wet rice cultivation (sawah) enabled the population to grow significantly, which contributed to the availability of labour and workforce for the state's public projects.

The bas-reliefs from temples of this period, especially from Borobudur and Prambanan describe occupations and careers other than agricultural pursuit; such as soldiers, government officials, court servants, massage therapists, travelling musicians and dancing troupe, food and drink sellers, logistics courier, sailors, merchants, even thugs and robbers are depicted in everyday life of 9th century Java.

The Wonoboyo hoard, golden artefacts discovered in 1990, revealed gold coins in shape similar to corn seeds, which suggests that 9th century Javan economy is partly monetised.

[3] The ancient Javanese did recognise the Hindu catur varna or caste social classes; Brahmana (priests), Kshatriya (kings, warlords and nobles), Vaishya (traders and artisans), and Shudra (servants and slaves).

The Sewu temple dedicated for Manjusri according to Kelurak inscription was probably initially built by Panangkaran, but later expanded and completed during Rakai Pikatan's rule, whom married to a Buddhist princess Pramodhawardhani, daughter of Samaratungga.

The Buddhist temple of Plaosan, Banyunibo and Sajiwan were built during the reign of King Pikatan and Queen Pramodhawardhani, probably in the spirit of religious reconciliation after the succession disputes between Pikatan-Pramodhawardhani against Balaputra.

Ranged from Karmavibhanga (the law of karma), Lalitavistara (the story of the Buddha), the tale of Manohara, Jataka and Jatakamala, Avadana (collection of virtuous deeds) and Gandavyuha (Sudhana's quest for the ultimate truth).

[119] Never before—and again—that Indonesia saw such vigorous passion for development and temple construction, which demonstrate such technological mastery, labour and resource management, aesthetics and art refinement, also architectural achievement, other than this era.

In southern Thailand, existed traces of Javanese art and architecture (erroneously referred to as "Srivijayan"), which probably demonstrate the Sailendra influences over Java, Sumatra and the Peninsula.