Resonance (chemistry)

It has particular value for analyzing delocalized electrons where the bonding cannot be expressed by one single Lewis structure.

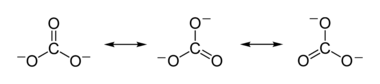

The resonance hybrid represents the actual molecule as the "average" of the contributing structures, with bond lengths and partial charges taking on intermediate values compared to those expected for the individual Lewis structures of the contributors, were they to exist as "real" chemical entities.

[4] Because electron delocalization lowers the potential energy of a system, any species represented by a resonance hybrid is more stable than any of the (hypothetical) contributing structures.

The magnitude of the resonance energy depends on assumptions made about the hypothetical "non-stabilized" species and the computational methods used and does not represent a measurable physical quantity, although comparisons of resonance energies computed under similar assumptions and conditions may be chemically meaningful.

[8] (As described below, the term "resonance" originated as a classical physics analogy for a quantum mechanical phenomenon, so it should not be construed too literally.)

is used to indicate that A and B are contributing forms of a single chemical species (as opposed to an equilibrium arrow, e.g.,

Nevertheless, describing the narwhal in terms of these imaginary creatures provides a reasonably good description of its physical characteristics.

All structures together may be enclosed in large square brackets, to indicate they picture one single molecule or ion, not different species in a chemical equilibrium.

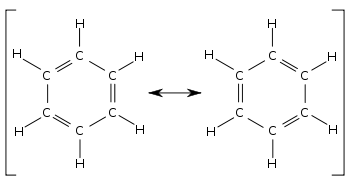

[11] The concept first appeared in 1899 in Johannes Thiele's "Partial Valence Hypothesis" to explain the unusual stability of benzene which would not be expected from August Kekulé's structure proposed in 1865 with alternating single and double bonds.

He compared the structure of the helium atom with the classical system of resonating coupled harmonic oscillators.

Linus Pauling used this mechanism to explain the partial valence of molecules in 1928, and developed it further in a series of papers in 1931-1933.

[15][16] The alternative term mesomerism[17] popular in German and French publications with the same meaning was introduced by C. K. Ingold in 1938, but did not catch on in the English literature.

Resonance theory dominated over competing Hückel method for two decades thanks to being relatively easier to understand for chemists without fundamental physics background, even if they couldn't grasp the concept of quantum superposition and confused it with tautomerism.

Pauling and Wheland themselves characterized Erich Hückel's approach as "cumbersome" at the time, and his lack of communication skills contributed: when Robert Robinson sent him a friendly request, he responded arrogantly that he is not interested in organic chemistry.

[18] In the Soviet Union, resonance theory – especially as developed by Pauling – was attacked in the early 1950s as being contrary to the Marxist principles of dialectical materialism, and in June 1951 the Soviet Academy of Sciences under the leadership of Alexander Nesmeyanov convened a conference on the chemical structure of organic compounds, attended by 400 physicists, chemists, and philosophers, where "the pseudo-scientific essence of the theory of resonance was exposed and unmasked".

[20] The issue of expansion of the valence shell of third period and heavier main group elements is controversial.

A Lewis structure in which a central atom has a valence electron count greater than eight traditionally implies the participation of d orbitals in bonding.

Nevertheless, by tradition, expanded octet structures are still commonly drawn for functional groups like sulfoxides, sulfones, and phosphorus ylides, for example.

A larger number of significant contributing structures and a more voluminous space available for delocalized electrons lead to stabilization (lowering of the energy) of the molecule.

The curved arrows depict the permutation of delocalized π electrons, which results in different contributors.

The allyl cation has two contributing structures with a positive charge on the terminal carbon atoms.

Often, reactive intermediates such as carbocations and free radicals have more delocalized structure than their parent reactants, giving rise to unexpected products.

[25] A well-studied example of delocalization that does not involve π electrons (hyperconjugation) can be observed in the non-classical 2-Norbornyl cation[26] Another example is methanium (CH+5).

These can be viewed as containing three-center two-electron bonds and are represented either by contributing structures involving rearrangement of σ electrons or by a special notation, a Y that has the three nuclei at its three points.

An example is the Friedel–Crafts alkylation[27] of benzene with 1-chloro-2-methylpropane; the carbocation rearranges to a tert-butyl group stabilized by hyperconjugation, a particular form of delocalization.

Resonance has a deeper significance in the mathematical formalism of valence bond theory (VB).

For example, in benzene, valence bond theory begins with the two Kekulé structures which do not individually possess the sixfold symmetry of the real molecule.

In general, the superposition is written with undetermined coefficients, which are then variationally optimized to find the lowest possible energy for the given set of basis wave functions.

The contributing structures in the VB model are particularly useful in predicting the effect of substituents on π systems such as benzene.

Weighting of the contributing structures in terms of their contribution to the overall structure can be calculated in multiple ways, using "Ab initio" methods derived from Valence Bond theory, or else from the Natural Bond Orbitals (NBO) approaches of Weinhold NBO5 Archived 2008-02-08 at the Wayback Machine, or finally from empirical calculations based on the Hückel method.