Metagenomics

[4] The term "metagenomics" was first used by Jo Handelsman, Robert M. Goodman, Michelle R. Rondon, Jon Clardy, and Sean F. Brady, and first appeared in publication in 1998.

In 2005, Kevin Chen and Lior Pachter (researchers at the University of California, Berkeley) defined metagenomics as "the application of modern genomics technique without the need for isolation and lab cultivation of individual species".

These surveys of ribosomal RNA genes taken directly from the environment revealed that cultivation based methods find less than 1% of the bacterial and archaeal species in a sample.

In the 1980s early molecular work in the field was conducted by Norman R. Pace and colleagues, who used PCR to explore the diversity of ribosomal RNA sequences.

Although this methodology was limited to exploring highly conserved, non-protein coding genes, it did support early microbial morphology-based observations that diversity was far more complex than was known by culturing methods.

Soon after that in 1995, Healy reported the metagenomic isolation of functional genes from "zoolibraries" constructed from a complex culture of environmental organisms grown in the laboratory on dried grasses.

[10] After leaving the Pace laboratory, Edward DeLong continued in the field and has published work that has largely laid the groundwork for environmental phylogenies based on signature 16S sequences, beginning with his group's construction of libraries from marine samples.

[11] In 2002, Mya Breitbart, Forest Rohwer, and colleagues used environmental shotgun sequencing (see below) to show that 200 liters of seawater contains over 5000 different viruses.

[12] Subsequent studies showed that there are more than a thousand viral species in human stool and possibly a million different viruses per kilogram of marine sediment, including many bacteriophages.

In 2004, Gene Tyson, Jill Banfield, and colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley and the Joint Genome Institute sequenced DNA extracted from an acid mine drainage system.

[21] Because the collection of DNA from an environment is largely uncontrolled, the most abundant organisms in an environmental sample are most highly represented in the resulting sequence data.

Misassemblies are caused by the presence of repetitive DNA sequences that make assembly especially difficult because of the difference in the relative abundance of species present in the sample.

[45] Recent methods, such as SLIMM, use read coverage landscape of individual reference genomes to minimize false-positive hits and get reliable relative abundances.

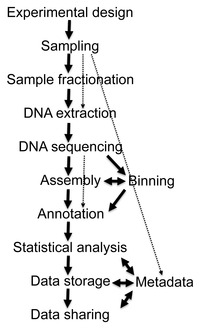

[27] The massive amount of exponentially growing sequence data is a daunting challenge that is complicated by the complexity of the metadata associated with metagenomic projects.

[51] Several tools have been developed to integrate metadata and sequence data, allowing downstream comparative analyses of different datasets using a number of ecological indices.

Faster and efficient tools are needed to keep pace with the high-throughput sequencing, because the BLAST-based approaches such as MG-RAST or MEGAN run slowly to annotate large samples (e.g., several hours to process a small/medium size dataset/sample [56]).

[59] Pairwise or multiple comparisons between metagenomes can be made at the level of sequence composition (comparing GC-content or genome size), taxonomic diversity, or functional complement.

[60] Functional comparisons between metagenomes may be made by comparing sequences against reference databases such as COG or KEGG, and tabulating the abundance by category and evaluating any differences for statistical significance.

[60] Consequently, metadata on the environmental context of the metagenomic sample is especially important in comparative analyses, as it provides researchers with the ability to study the effect of habitat upon community structure and function.

A GUI-based comparative metagenomic analysis application called Community-Analyzer has been developed by Kuntal et al. [65] which implements a correlation-based graph layout algorithm that not only facilitates a quick visualization of the differences in the analyzed microbial communities (in terms of their taxonomic composition), but also provides insights into the inherent inter-microbial interactions occurring therein.

[66] In one such system, the methanogenic bioreactor, functional stability requires the presence of several syntrophic species (Syntrophobacterales and Synergistia) working together in order to turn raw resources into fully metabolized waste (methane).

Because of the technical difficulties (the short half-life of mRNA, for example) in the collection of environmental RNA there have been relatively few in situ metatranscriptomic studies of microbial communities to date.

[80] Microbial consortia perform a wide variety of ecosystem services necessary for plant growth, including fixing atmospheric nitrogen, nutrient cycling, disease suppression, and sequester iron and other metals.

[28] Metagenomic approaches to the analysis of complex microbial communities allow the targeted screening of enzymes with industrial applications in biofuel production, such as glycoside hydrolases.

Metagenomic approaches allow comparative analyses between convergent microbial systems like biogas fermenters[85] or insect herbivores such as the fungus garden of the leafcutter ants.

[60][87] The application of metagenomics has allowed the development of commodity and fine chemicals, agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals where the benefit of enzyme-catalyzed chiral synthesis is increasingly recognized.

[94] DNA sequencing can also be used more broadly to identify species present in a body of water,[95] debris filtered from the air, sample of dirt, or animal's faeces,[96] and even detect diet items from blood meals.

Using the relative gene frequencies found within the gut these researchers identified 1,244 metagenomic clusters that are critically important for the health of the intestinal tract.

These included glycosaminoglycan degradation in the gut, as well as phosphate and amino acid transport linked to host phenotype (vaginal pH) in the posterior fornix.

Clinical metagenomic sequencing shows promise as a sensitive and rapid method to diagnose infection by comparing genetic material found in a patient's sample to databases of all known microscopic human pathogens and thousands of other bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic organisms and databases on antimicrobial resistances gene sequences with associated clinical phenotypes.