Metallic bonding

In both models, the electrons are seen as a gas traveling through the structure of the solid with an energy that is essentially isotropic, in that it depends on the square of the magnitude, not the direction of the momentum vector k. In three-dimensional k-space, the set of points of the highest filled levels (the Fermi surface) should therefore be a sphere.

In the nearly-free model, box-like Brillouin zones are added to k-space by the periodic potential experienced from the (ionic) structure, thus mildly breaking the isotropy.

The advent of X-ray diffraction and thermal analysis made it possible to study the structure of crystalline solids, including metals and their alloys; and phase diagrams were developed.

Despite all this progress, the nature of intermetallic compounds and alloys largely remained a mystery and their study was often merely empirical.

Chemists generally steered away from anything that did not seem to follow Dalton's laws of multiple proportions; and the problem was considered the domain of a different science, metallurgy.

The nearly-free electron model was eagerly taken up by some researchers in metallurgy, notably Hume-Rothery, in an attempt to explain why intermetallic alloys with certain compositions would form and others would not.

His idea was to add electrons to inflate the spherical Fermi-balloon inside the series of Brillouin-boxes and determine when a certain box would be full.

A number of quantum mechanical models were developed, such as band structure calculations based on molecular orbitals, and the density functional theory.

Rudolf Peierls showed that, in the case of a one-dimensional row of metallic atoms—say, hydrogen—an inevitable instability would break such a chain into individual molecules.

Researchers such as Mott and Hubbard realized that the one-electron treatment was perhaps appropriate for strongly delocalized s- and p-electrons; but for d-electrons, and even more for f-electrons, the interaction with nearby individual electrons (and atomic displacements) may become stronger than the delocalized interaction that leads to broad bands.

This gave a better explanation for the transition from localized unpaired electrons to itinerant ones partaking in metallic bonding.

It describes the bonding only as present in a chunk of condensed matter: be it crystalline solid, liquid, or even glass.

Metallic vapors, in contrast, are often atomic (Hg) or at times contain molecules, such as Na2, held together by a more conventional covalent bond.

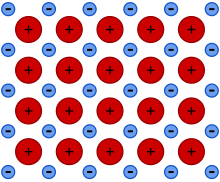

For caesium, therefore, the picture of Cs+ ions held together by a negatively charged electron gas is very close to accurate (though not perfectly so).

The freedom of electrons to migrate also gives metal atoms, or layers of them, the capacity to slide past each other.

Metals are typically also good conductors of heat, but the conduction electrons only contribute partly to this phenomenon.

Collective (i.e., delocalized) vibrations of the atoms, known as phonons that travel through the solid as a wave, are bigger contributors.

Between the 4d and 5d elements, the lanthanide contraction is observed—there is very little increase of the radius down the group due to the presence of poorly shielding f orbitals.

[7] This typically results in metals assuming relatively simple, close-packed crystal structures, such as FCC, BCC, and HCP.

Given high enough cooling rates and appropriate alloy composition, metallic bonding can occur even in glasses, which have amorphous structures.

If the structures of the two metals are the same, there can even be complete solid solubility, as in the case of electrum, an alloy of silver and gold.

But, because materials with metallic bonding are typically not molecular, Dalton's law of integral proportions is not valid; and often a range of stoichiometric ratios can be achieved.

It is possible to observe which elements do partake: e.g., by looking at the core levels in an X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum.

Some intermetallic materials, e.g., do exhibit metal clusters reminiscent of molecules; and these compounds are more a topic of chemistry than of metallurgy.

The core of the planet Jupiter could be said to be held together by a combination of metallic bonding and high pressure induced by gravity.

As these phenomena involve the movement of the atoms toward or away from each other, they can be interpreted as the coupling between the electronic and the vibrational states (i.e. the phonons) of the material.

The balance between reflection and absorption determines how white or how gray a metal is, although surface tarnish can obscure the lustre.

The momentum selection rule is therefore broken, and the plasmon resonance causes an extremely intense absorption in the green, with a resulting purple-red color.

Such colors are orders of magnitude more intense than ordinary absorptions seen in dyes and the like, which involve individual electrons and their energy states.