Military history of New Zealand

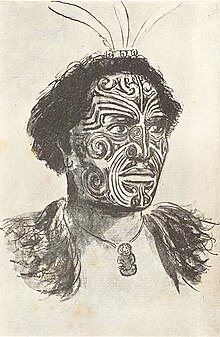

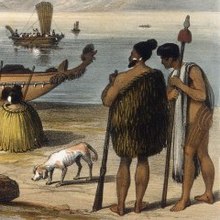

The early 19th century saw the outbreak of the Musket Wars, where the introduction of firearms intensified Māori conflicts and led to significant shifts in tribal dynamics and territorial boundaries.

[1] Wars eventually broke out between tribal groups for practical reasons like population pressures, competition for land and natural resources, and the need to protect food supplies.

The continuous peace was established after a series of conflicts, when a local chief, Nunuku-whenua, declared an end to war, and a permanent restriction on murder and cannibalism.

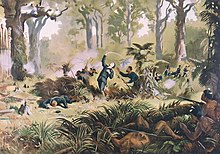

[21] As imperial forces scaled back their involvement, the burden of fighting on the Crown side increasingly fell on colonial troops and the kūpapa, many of whom were Māori who were committed to traditional Christianity and resisted the Kīngitangapā movement.

[27] Upon hearing that a taua was approaching Wellington, Grey extended martial law to Whanganui, and urged Te Āti Awa to intercept them, which they agreed to do.

Tensions were further exacerbated after Whanganui rangatira Hapurona Ngārangi was shot, and followers of Te Mamaku attacked an isolated farm in Matarawa valley and killed four residents.

The British subsequently attacked Te Āti Awa forces at Puketakauere pā in June 1860, although later withdrew to Waitara after sustaining heavy losses.

In September, Pratt organised several raids against Te Āti Awa strongholds along the upper Waitara River and defeated a Ngāti Hāua war party in November.

Realising that his force could only take the fortifications with high casualties, the British commander, Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron, opted instead to move around the southern flank of defences to reach food-producing villages like Rangiaowhia.

From December to February, Chute's force conducted a route march aimed at destroying Taranaki Māori capacity for war by burning villages and livestock.

[32] In July 1868, Te Kooti, the Ringatū founder, and 297 of his followers seized a schooner and forced its crew to sail them south of Poverty Bay, prompting colonial authorities to seek his capture.

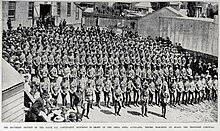

On 28 September 1899, two weeks before the start of the conflict, the New Zealand House of Representatives approved the formation of a 200-man mounted rifle contingent for service in South Africa, in a show of colonial solidarity aimed at deterring the Boers from fighting.

[45] As they were in the region, the NZEF and AIF were drawn into Allied plans to capture the Dardanelles Strait so naval forces could directly attack the Ottoman capital, Constantinople.

[53] By 1916, NZEF efforts were reoriented to the Western Front, with the New Zealand Division landing in France in April 1916, and its expeditionary headquarters established at Sling Camp in the Salisbury Plain Training Area.

[67] In October 1943, the 2nd New Zealand Division was deployed to Italy and took part in several engagements during the Italian campaign, including the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944, and the Operation Grapeshot in 1945.

The Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) dispatched the cruisers HMNZS Leander and Achilles successively to the Solomon Islands, although both were damaged by enemy action.

41 Squadron RNZAF was based in the colony of Singapore, and was attached to the RAF Far East Air Force, a unit that flew regular sorties to British Hong Kong.

[77] In April 1951, during the Battle of Kapyong, the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade fought a successful defence against a Chinese division, with New Zealand gunners providing vital artillery support to Allied forces.

A New Zealand Special Air Service (NZSAS) squadron was deployed near the Perak and Kelantan border in 1956 and Negri Sembilan in 1957, eliminating local MNLA groups in those areas.

[81] In February 1965, the New Zealand government approved the deployment of a Special Air Service detachment to Borneo, and two additional RNZN minesweepers to join HMNZS Taranaki in patrolling the Malacca Strait.

After the Indonesian-Malaysian Confrontation ended, New Zealand faced renewed pressure from the US to expand its commitment, resulting in the dispatch of two additional infantry companies in 1967 and an NZSAS unit the next year.

[93] The NZDF confirmed that it planned to end its 20-year deployment in May 2021, with the withdrawal of six personnel from the Afghan National Army's Officer Academy and NATO's Resolute Support Mission Headquarters.

[103] New Zealand's commitment to the Balkan states commenced in 1992 with the deployment of five soldiers as UN Military Observers serving with the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR).

New Zealand's contribution in East Timor included SAS special forces, infantry battalion and helicopters, backed by RNZN warships and RNZAF transport.

In addition to their operations against militia, the New Zealand troops were also involved in construction of roads and schools, water supplies, training the nascent Timor Leste Defence Force (F-FDTL) and other infrastructural assistance.

Troops supervised the concentration of the guerrilla forces into sixteen Assembly Places during the period in which the cease fire was implemented and national elections held.

New Zealand increased its commitment to this Mission, which is now tri-service in nature, with a group of about two platoons of specialist servicemen and women serving a six-month Tour of Duty with the MFO.

RAMSI acted as an interim police force and has been successful in improving the country's overall security conditions, including brokering the surrender of a notorious warlord, Harold Keke.

[116][117] In accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1483 New Zealand also contributed a small engineering and support force to assist in post-war reconstruction and provision of humanitarian aid.

5 Squadron has operated in the airspace over and near Scott Base to provide search and rescue standby and to drop mail and medical supplies to the people wintering over.