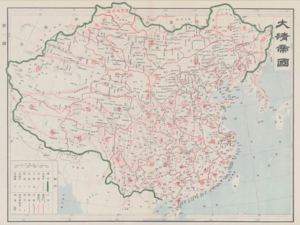

Transition from Ming to Qing

[32] The Ming general Li Yongfang who surrendered the city of Fushun in what is now Liaoning province in China's northeast did so after Nurhaci gave him an Aisin Gioro princess in marriage and a noble title.

However, Han Chinese officials Ning Wanwo (寧完我), Fan Wencheng, Ma Guozhu (馬國柱), Zu Kefa (祖可法), Shen Peirui (沈佩瑞), and Zhang Wenheng (張文衡) urged him to declare himself as Emperor of China.

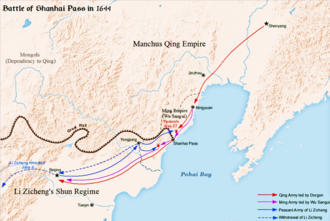

[113] With the fall of Songshan and Jinzhou, the Ming defense system in Liaoxi collapsed, leaving Wu Sangui's forces near the Shanhai Pass as the last barrier on the Qing armies' way to Beijing.

[120][121][122][123] After declaring his own Shun dynasty in Beijing, Li Zicheng sent an offer to the powerful Ming general at the Great Wall, Wu Sangui, to defect to his side in exchange for a high noble rank and title.

[127] Two of Dorgon's most prominent Chinese advisors, Hong Chengchou[128] and Fan Wencheng, urged the Manchu prince to seize the opportunity of the fall of Beijing to present themselves as avengers of the fallen Ming and to claim the Mandate of Heaven for the Qing.

This allowed the Qing dynasty to capture an entire corps of qualified civil servants to administer the country, and also ensured that the Southern Ming pretenders would suffer from infighting due to their weak claims on the throne.

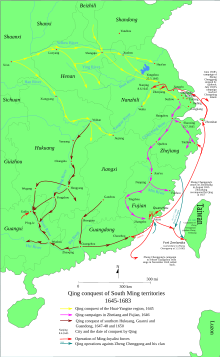

[149] The Qing carried out a massive depopulation policy and clearances, forcing people to evacuate the coast in order to deprive Koxinga's Ming loyalists of resources: this led to a myth that it was because Manchus were "afraid of water".

In fact, in Guangdong and Fujian, it was Han Bannermen who were the ones carrying out the fighting and killing for the Qing and this disproves the claim that "fear of water" on part of the Manchus had to do with the coastal evacuation to move inland and declare the sea ban.

[151] Soon after entering Beijing in June 1644, Dorgon despatched Wu Sangui and his troops to pursue Li Zicheng, the rebel leader who had driven the last Ming emperor to suicide, but had been defeated by the Qing in late May at the Battle of Shanhai Pass.

[156] Pursued by Ajige, Li retreated down the Han River into Wuchang, Hubei, and further to Tongcheng and the Jiugong Mountains until he was killed in September 1645, either by his own hand or by a peasant group that had organized for self-defense in this time of rampant banditry.

[183] Ming loyalist Ma Shiying had brought to Nanjing troops from the western provinces made out of non-Han Chinese indigenous fierce tribal warriors called "Sichuan" soldiers to defend the city against the Qing.

Then a group of Qing Han Chinese and Banner soldiers showed up to Huang Degong's camp in Wuhu on 15 June 1645, under Zhang Tianlu, the Guazhou garrison commander, bannermen from Dodo and general Liu Liangzuo.

[196] With the news of the fall of the capital back in 1644 and skyrocketing food prices, poor peasants had revolted against the local elite and indentured servitude, calling that "master and servant should address each other as brothers".

[197] On 21 July 1645, after the Jiangnan region had been superficially pacified, Dorgon issued "the most untimely promulgation of his career":[198] he ordered all Chinese men to shave their forehead and to braid the rest of their hair into a queue just like the Manchus.

East of the lake, loyalist gentry in Songjiang District under Chen Zilong and the remaining Ming navy at Chongming Island under Wu Zhikui coordinated to rise up and cut off the Qing forces in Zhejiang.

[217] In Fuzhou, although former-Ming subjects were initially compensated with silver for complying to the Queue Order, the defected southern Chinese general Hong Chengchou had enforced the policy thoroughly on the residents of Jiangnan by 1645.

[222] Loyalist marines continued fighting in the Lake Tai area, under Wu Yi and Zhou Rui, mainly local fishermen and smugglers, which posed a problem for Qing forces who lacked competent sailors.

Qing forces mainly left the province due to starvation and the remainder garrisoned at Baoning in the north under Li Guoying, who moved to crush banditry, called for supplies to be shipped in and recultivated the land to relieve the famine-like conditions.

In response, the Longwu emperor wanted to reconquer Huguang and Jiangxi provinces which were major producers of rice to help boost the southern Ming, but Zheng Zhilong refused to expand out of Fujian for fear of losing control of the regime.

[243] Hoping to gain rewards from Prince Bolo, Zheng Zhilong betrayed the loyalists by contacting Hong Chengchou and left northern Fujian undefended against a Qing army led by Li Chengdong and Tong Yangjia.

[250] The Longwu Emperor's younger brother Zhu Yuyue, who had fled Fuzhou by sea, soon founded another Ming regime in Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province, taking the reign title Shaowu (紹武) on 11 December 1646.

Simultaneously, Zhu Senfu, a man who claimed to be related to the Ming Imperial family, declared himself Prince of Qin in Jiezhou, Shaanxi, near Sichuan, backed by a local outlaw named Zhao Ronggui with an army of 10,000 men.

In early August 1652, Li Dingguo, who had served as general in Sichuan under Zhang Xianzhong (d. 1647) and was now protecting the Yongli Emperor of the Southern Ming, retook Guilin (Guangxi province) from the Qing.

During the fighting to extinguish Ming loyalism in the south, the Shunzhi Emperor came to rely increasingly on Han Chinese bannermen, some second or even third generation, to fill governor and governor-general posts as a kind of "provincial janissaries".

[273] In late January 1659, a Qing army led by Manchu Prince Doni (1636–1661), Dodo's son, took the capital of Yunnan, sending the Yongli Emperor fleeing into nearby Burma, which was then ruled by King Pindale Min of the Toungoo dynasty.

In Yunnan, the banner troops had engaged in pillage and rape when moving through Hmong lands, and the chieftain Nayan, under the promise of being given overall command of all the tusi chiefs, rose in rebellion on the side of the Yongli Emperor.

[281] In 1659, just as Shunzhi was preparing to hold a special examination to celebrate the glories of his reign and the success of the southwestern campaigns, Zheng sailed up the Yangtze River with a well-armed fleet, took several cities from Qing hands, and went so far as to threaten Nanjing.

Koxinga's attack on Qing held Nanjing which would interrupt the supply route of the Grand Canal leading to possible starvation in Beijing caused such fear that the Manchus considered returning to Manchuria (Tartary) and abandoning China according to a 1671 account by a French missionary.

Shang Zhixin and Geng Jimao surrendered in 1681 after a massive Qing counteroffensive, in which the Han Chinese Green Standard Army played the major role with the Bannermen taking a backseat.

His descendants resisted Qing rule until 1683, when the Kangxi Emperor dispatched Shi Lang with a fleet of 300 ships to take the Ming loyalist Kingdom of Tungning in Taiwan in 1683 from the Zheng family.