DNA mismatch repair

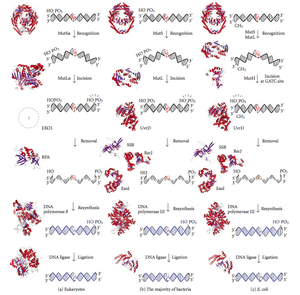

Loaded PCNA then directs the action of the MutLalpha endonuclease [5] to the daughter strand in the presence of a mismatch and MutSalpha or MutSbeta.

Any mutational event that disrupts the superhelical structure of DNA carries with it the potential to compromise the genetic stability of a cell.

The fact that the damage detection and repair systems are as complex as the replication machinery itself highlights the importance evolution has attached to DNA fidelity.

The damage is repaired by recognition of the deformity caused by the mismatch, determining the template and non-template strand, and excising the wrongly incorporated base and replacing it with the correct nucleotide.

Subsequent work on E. coli has identified a number of genes that, when mutationally inactivated, cause hypermutable strains.

The gene products are, therefore, called the "Mut" proteins, and are the major active components of the mismatch repair system.

MutS forms a dimer (MutS2) that recognises the mismatched base on the daughter strand and binds the mutated DNA.

The entire MutSHL complex then slides along the DNA in the direction of the mismatch, liberating the strand to be excised as it goes.

It has weak ATPase activity, and binding of ATP leads to the formation of tertiary structures on the surface of the molecule.

The crystal structure of MutS reveals that it is exceptionally asymmetric, and, while its active conformation is a dimer, only one of the two halves interacts with the mismatch site.

Because the distance between the nick created by MutH and the mismatch can average ~600 bp, if there is not another UvrD loaded the unwound section is then free to re-anneal to its complementary strand, forcing the process to start over.

If both inherited copies (alleles) of a MMR gene bear damaging genetic variants, this results in a very rare and severe condition: the mismatch repair cancer syndrome (or constitutional mismatch repair deficiency, CMMR-D), manifesting as multiple occurrences of tumors at an early age, often colon and brain tumors.

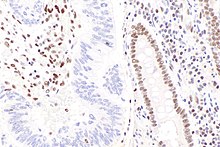

[10] Other cancer types have higher frequencies of MLH1 loss (see table below), which are again largely a result of methylation of the promoter of the MLH1 gene.

A different epigenetic mechanism underlying MMR deficiencies might involve over-expression of a microRNA, for example miR-155 levels inversely correlate with expression of MLH1 or MSH2 in colorectal cancer.

"[20][21] Similarly, Vogelstein et al.[22] point out that more than half of somatic mutations identified in tumors occurred in a pre-neoplastic phase (in a field defect), during growth of apparently normal cells.

MMR and mismatch repair mutations were initially observed to associate with immune checkpoint blockade efficacy in a study examining responders to anti-PD1.

[33] In contrast, the gene-poor, late-replicating heterochromatic genome regions exhibit high mutation rates in many human tumors.

[35] Consistently, regions of the human genome with high levels of H3K36me3 accumulate less mutations due to MMR activity.

Mice defective in the mutL homolog Pms2 have about a 100-fold elevated mutation frequency in all tissues, but do not appear to age more rapidly.

[38] These mice display mostly normal development and life, except for early onset carcinogenesis and male infertility.