History of astronomy

It is generally believed that the first astronomers were priests, and that they understood celestial objects and events to be manifestations of the divine, hence early astronomy's connection to what is now called astrology.

[8] It has also been suggested that drawings on the wall of the Lascaux caves in France dating from 33,000 to 10,000 years ago could be a graphical representation of the Pleiades, the Summer Triangle, and the Northern Crown.

Among the discoveries are: The origins of astronomy can be found in Mesopotamia, the "land between the rivers" Tigris and Euphrates, where the ancient kingdoms of Sumer, Assyria, and Babylonia were located.

Mesopotamia is worldwide the place of the earliest known astronomer and poet by name: Enheduanna, Akkadian high priestess to the lunar deity Nanna/Sin and princess, daughter of Sargon the Great (c. 2334 – c. 2279 BCE).

[26] Classical sources frequently use the term Chaldeans for the astronomers of Mesopotamia, who were originally a people, before being identified with priest-scribes specializing in astrology and other forms of divination.

The MUL.APIN, contains catalogues of stars and constellations as well as schemes for predicting heliacal risings and the settings of the planets, lengths of daylight measured by a water clock, gnomon, shadows, and intercalations.

The systematic records of ominous phenomena in Babylonian astronomical diaries that began at this time allowed for the discovery of a repeating 18-year cycle of lunar eclipses, for example.

[29] As the Indus Valley civilization did not leave behind written documents, the oldest extant Indian astronomical text is the Vedanga Jyotisha, dating from the Vedic period.

[30] The Vedanga Jyotisha is attributed to Lagadha and has an internal date of approximately 1350 BC, and describes rules for tracking the motions of the Sun and the Moon for the purposes of ritual.

[29][31][32] Aryabhata (476–550), in his magnum opus Aryabhatiya (499), propounded a computational system based on a planetary model in which the Earth was taken to be spinning on its axis and the periods of the planets were given with respect to the Sun.

The first geometrical, three-dimensional models to explain the apparent motion of the planets were developed in the 4th century BC by Eudoxus of Cnidus and Callippus of Cyzicus.

In his Timaeus, Plato described the universe as a spherical body divided into circles carrying the planets and governed according to harmonic intervals by a world soul.

[36] Aristotle, drawing on the mathematical model of Eudoxus, proposed that the universe was made of a complex system of concentric spheres, whose circular motions combined to carry the planets around the Earth.

Hipparchus made a number of other contributions, including the first measurement of precession and the compilation of the first star catalog in which he proposed our modern system of apparent magnitudes.

In his Planetary Hypotheses, Ptolemy ventured into the realm of cosmology, developing a physical model of his geometric system, in a universe many times smaller than the more realistic conception of Aristarchus of Samos four centuries earlier.

The precise orientation of the Egyptian pyramids affords a lasting demonstration of the high degree of technical skill in watching the heavens attained in the 3rd millennium BC.

They have been identified with two inscribed objects in the Berlin Museum; a short handle from which a plumb line was hung, and a palm branch with a sight-slit in the broader end.

Maya astronomical codices include detailed tables for calculating phases of the Moon, the recurrence of eclipses, and the appearance and disappearance of Venus as morning and evening star.

The Maya based their calendrics in the carefully calculated cycles of the Pleiades, the Sun, the Moon, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Mars, and also they had a precise description of the eclipses as depicted in the Dresden Codex, as well as the ecliptic or zodiac, and the Milky Way was crucial in their Cosmology.

His practical manuals for training astrologers profoundly influenced Muslim intellectual history and, through translations, that of western Europe and Byzantium In the 10th century,[52] Albumasar's "Introduction" was one of the most important sources for the recovery of Aristotle for medieval European scholars.

He noted that measurements by earlier (Indian, then Greek) astronomers had found higher values for this angle, possible evidence that the axial tilt is not constant but was in fact decreasing.

The advanced astronomical treatises of classical antiquity were written in Greek, and with the decline of knowledge of that language, only simplified summaries and practical texts were available for study.

[69] In the 7th century the English monk Bede of Jarrow published an influential text, On the Reckoning of Time, providing churchmen with the practical astronomical knowledge needed to compute the proper date of Easter using a procedure called the computus.

[70] The range of surviving ancient Roman writings on astronomy and the teachings of Bede and his followers began to be studied in earnest during the revival of learning sponsored by the emperor Charlemagne.

[72] Building on this astronomical background, in the 10th century European scholars such as Gerbert of Aurillac began to travel to Spain and Sicily to seek out learning which they had heard existed in the Arabic-speaking world.

Descartes' theory of vortices held sway in France, and Huygens, Leibniz and Cassini accepted only parts of Newton's system, preferring their own philosophies.

Edmond Halley published the first measurements of the proper motion of a pair of nearby "fixed" stars, demonstrating that they had changed positions since the time of the ancient Greek astronomers Ptolemy and Hipparchus.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt discovered the cepheid variable star period-luminosity relation which she further developed into a method of measuring distance outside of the Solar System.

A veteran of the Harvard Computers, Annie J. Cannon developed the modern version of the stellar classification scheme in during the early 1900s (O B A F G K M, based on color and temperature), manually classifying more stars in a lifetime than anyone else (around 350,000).

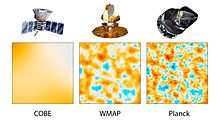

Physical cosmology, a discipline that has a large intersection with astronomy, made huge advances during the 20th century, with the model of the hot Big Bang heavily supported by the evidence provided by astronomy and physics, such as the redshifts of very distant galaxies and radio sources, the cosmic microwave background radiation, Hubble's law and cosmological abundances of elements.