Molecular orbital theory

These approximations are made by applying the density functional theory (DFT) or Hartree–Fock (HF) models to the Schrödinger equation.

The variational principle is a mathematical technique used in quantum mechanics to build up the coefficients of each atomic orbital basis.

An additional unitary transformation can be applied on the system to accelerate the convergence in some computational schemes.

Changes to the electronic structure of molecules can be seen by the absorbance of light at specific wavelengths.

Molecular orbital theory was developed in the years after valence bond theory had been established (1927), primarily through the efforts of Friedrich Hund, Robert Mulliken, John C. Slater, and John Lennard-Jones.

[5] According to physicist and physical chemist Erich Hückel, the first quantitative use of molecular orbital theory was the 1929 paper of Lennard-Jones.

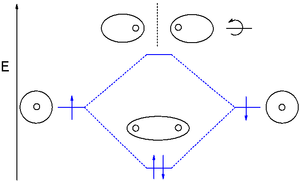

[10] Erich Hückel applied molecular orbital theory to unsaturated hydrocarbon molecules starting in 1931 with his Hückel molecular orbital (HMO) method for the determination of MO energies for pi electrons, which he applied to conjugated and aromatic hydrocarbons.

[11][12] This method provided an explanation of the stability of molecules with six pi-electrons such as benzene.

The first accurate calculation of a molecular orbital wavefunction was that made by Charles Coulson in 1938 on the hydrogen molecule.

[13] By 1950, molecular orbitals were completely defined as eigenfunctions (wave functions) of the self-consistent field Hamiltonian and it was at this point that molecular orbital theory became fully rigorous and consistent.

[15] This led to the development of many ab initio quantum chemistry methods.

It can be detected under very low temperature and pressure molecular beam and has binding energy of approximately 0.001 J/mol.

In MO theory, any electron in a molecule may be found anywhere in the molecule, since quantum conditions allow electrons to travel under the influence of an arbitrarily large number of nuclei, as long as they are in eigenstates permitted by certain quantum rules.

Thus, when excited with the requisite amount of energy through high-frequency light or other means, electrons can transition to higher-energy molecular orbitals.

Although in MO theory some molecular orbitals may hold electrons that are more localized between specific pairs of molecular atoms, other orbitals may hold electrons that are spread more uniformly over the molecule.

Robert S. Mulliken, who actively participated in the advent of molecular orbital theory, considers each molecule to be a self-sufficient unit.

He asserts in his article: ...Attempts to regard a molecule as consisting of specific atomic or ionic units held together by discrete numbers of bonding electrons or electron-pairs are considered as more or less meaningless, except as an approximation in special cases, or as a method of calculation […].

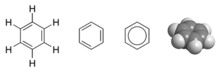

A molecule is here regarded as a set of nuclei, around each of which is grouped an electron configuration closely similar to that of a free atom in an external field, except that the outer parts of the electron configurations surrounding each nucleus usually belong, in part, jointly to two or more nuclei....[18]An example is the MO description of benzene, C6H6, which is an aromatic hexagonal ring of six carbon atoms and three double bonds.

As in the VB theory, all of these six delocalized π electrons reside in a larger space that exists above and below the ring plane.

In MO theory this is a direct consequence of the fact that the three molecular π orbitals combine and evenly spread the extra six electrons over six carbon atoms.

In molecules such as methane, CH4, the eight valence electrons are found in four MOs that are spread out over all five atoms.

Linus Pauling, in 1931, hybridized the carbon 2s and 2p orbitals so that they pointed directly at the hydrogen 1s basis functions and featured maximal overlap.

However, the delocalized MO description is more appropriate for predicting ionization energies and the positions of spectral absorption bands.

Triply degenerate T2 and A1 ionized states (CH4+) are produced from different linear combinations of these four structures.

As in benzene, in substances such as beta carotene, chlorophyll, or heme, some electrons in the π orbitals are spread out in molecular orbitals over long distances in a molecule, resulting in light absorption in lower energies (the visible spectrum), which accounts for the characteristic colours of these substances.

This results from continuous band overlap of half-filled p orbitals and explains electrical conduction.

MO theory recognizes that some electrons in the graphite atomic sheets are completely delocalized over arbitrary distances, and reside in very large molecular orbitals that cover an entire graphite sheet, and some electrons are thus as free to move and therefore conduct electricity in the sheet plane, as if they resided in a metal.