Monetarism

It gained prominence in the 1970s but was mostly abandoned as a direct guidance to monetary policy during the following decade because of the rise of inflation targeting through movements of the official interest rate.

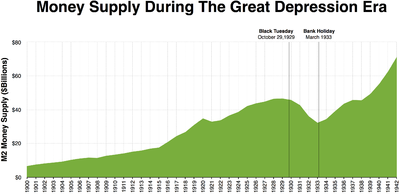

The monetarist theory states that variations in the money supply have major influences on national output in the short run and on price levels over longer periods.

Instead, starting in the early 1990s, most major central banks turned to direct inflation targeting, relying on steering short-run interest rates as their main policy instrument.

Formulated by Milton Friedman, it argues that excessive expansion of the money supply is inherently inflationary, and that monetary authorities should focus solely on maintaining price stability.

It attributed deflationary spirals to the reverse effect of a failure of a central bank to support the money supply during a liquidity crunch.

[11] Clark Warburton is credited with making the first solid empirical case for the monetarist interpretation of business fluctuations in a series of papers from 1945.[1]p.

[13] In May 1979, Margaret Thatcher, Leader of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom, won the general election, defeating the sitting Labour Government led by James Callaghan.

[10] The period when major central banks focused on targeting the growth of money supply, reflecting monetarist theory, lasted only for a few years, in the US from 1979 to 1982.

[5]: 483–485 While monetarism's influence on policy diminished in the 1980s, subsequent research suggests that the apparent instability in money demand functions may have stemmed from measurement issues rather than a fundamental breakdown in the money-income relationship.

For instance, Belongia and Ireland demonstrated that money demand equations using Divisia measures remain stable even through periods of financial innovation and policy regime changes that destabilized traditional simple-sum specifications.

The breakdown in simple-sum money demand relationships was a key factor in central banks abandoning monetary targeting in favor of interest rate rules.

For example, Hendrickson found that replacing simple-sum with Divisia measures resolves apparent instabilities in U.S. money demand, while similar results have been documented for other economies.

[20] Chen and Valcarcel argued that the properly measured monetary quantities and their holding costs maintain a stable, long-term cointegration.

[21] These findings suggest that the historical shift away from monetary aggregates in policy frameworks may have been premature and based on flawed measurement rather than a true breakdown in the relationship between money and economic activity.

While most central banks continue to focus primarily on interest rates, the stability of properly-measured money demand functions indicates that monetary aggregates could potentially play a more prominent role in policy frameworks.