Modern synthesis (20th century)

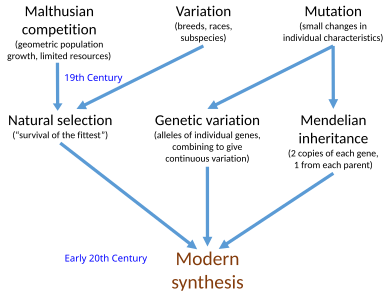

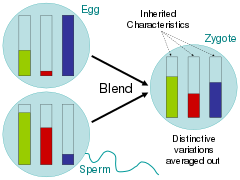

Darwin believed in blending inheritance, which implied that any new variation, even if beneficial, would be weakened by 50% at each generation, as the engineer Fleeming Jenkin noted in 1868.

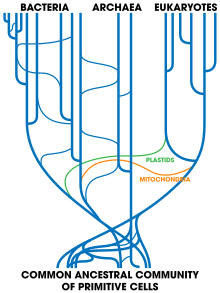

[16][17] While carrying out breeding experiments to clarify the mechanism of inheritance in 1900, Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns independently rediscovered Gregor Mendel's work.

[23][24] A traditional view is that the biometricians and the Mendelians rejected natural selection and argued for their separate theories for 20 years, the debate only resolved by the development of population genetics.

[23][25] A more recent view is that Bateson, de Vries, Thomas Hunt Morgan and Reginald Punnett had by 1918 formed a synthesis of Mendelism and mutationism.

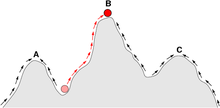

The understanding achieved by these geneticists spanned the action of natural selection on alleles (alternative forms of a gene), the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, the evolution of continuously varying traits (like height), and the probability that a new mutation will become fixed.

In this view, the early geneticists accepted natural selection but rejected Darwin's non-Mendelian ideas about variation and heredity, and the synthesis began soon after 1900.

He then tried selecting different groups for bigger or smaller stripes for 5 generations and found that it was possible to change the characteristics considerably beyond the initial range of variation.

[31][32][33] Thomas Hunt Morgan began his career in genetics as a saltationist and started out trying to demonstrate that mutations could produce new species in fruit flies.

However, the experimental work at his lab with the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster[c] showed that rather than creating new species in a single step, mutations increased the supply of genetic variation in the population.

He criticised the traditional natural history style of biology, including the study of evolution, as immature science, since it relied on narrative.

The Harvard physiologist William John Crozier told his students that evolution was not even a science: "You can't experiment with two million years!

[38] In 1918, R. A. Fisher wrote "The Correlation between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance,"[39] which showed how continuous variation could come from a number of discrete genetic loci.

[43] Both of these scholars, and others, such as Dobzhansky and Wright, wanted to raise biology to the standards of the physical sciences by basing it on mathematical modeling and empirical testing.

[41][53] Wright's model appealed to field naturalists such as Theodosius Dobzhansky and Ernst Mayr who were becoming aware of the importance of geographical isolation in real world populations.

[54][55][56] Theodosius Dobzhansky, an immigrant from the Soviet Union to the United States, who had been a postdoctoral worker in Morgan's fruit fly lab, was one of the first to apply genetics to natural populations.

[41][43] By 1937, Dobzhansky was able to argue that mutations were the main source of evolutionary changes and variability, along with chromosome rearrangements, effects of genes on their neighbours during development, and polyploidy.

[61][62] His 1949 book Mendelism and Evolution[63] helped to persuade Dobzhansky to change the emphasis in the third edition of his famous textbook Genetics and the Origin of Species from drift to selection.

The book was successful in its goal of persuading readers of the reality of evolution, effectively illustrating topics such as island biogeography, speciation, and competition.

Huxley further showed that the appearance of long-term orthogenetic trends – predictable directions for evolution – in the fossil record were readily explained as allometric growth (since parts are interconnected).

[70] Huxley's belief in progress within evolution and evolutionary humanism was shared in various forms by Dobzhansky, Mayr, Simpson and Stebbins, all of them writing about "the future of Mankind".

[41][43][75][76] Before he left Germany for the United States in 1930, Mayr had been influenced by the work of the German biologist Bernhard Rensch, who in the 1920s had analyzed the geographic distribution of polytypic species, paying particular attention to how variations between populations correlated with factors such as differences in climate.

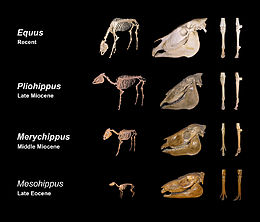

It showed that the trends of linear progression (in for example the evolution of the horse) that earlier palaeontologists had used as support for neo-Lamarckism and orthogenesis did not hold up under careful examination.

Everything fitted into the new framework, except "heretics" like Richard Goldschmidt who annoyed Mayr and Dobzhansky by insisting on the possibility of speciation by macromutation, creating "hopeful monsters".

After the synthesis, evolutionary biology continued to develop with major contributions from workers including W. D. Hamilton,[85] George C. Williams,[86] E. O. Wilson,[87] Edward B. Lewis[88] and others.

Smocovitis commented on this that "What the architects of the synthesis had worked to construct had by 1982 become a matter of fact", adding in a footnote that "the centrality of evolution had thus been rendered tacit knowledge, part of the received wisdom of the profession".

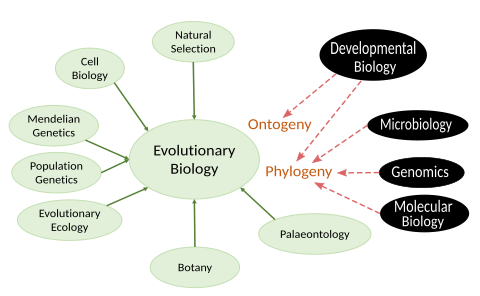

[95] By the late 20th century, however, the modern synthesis was showing its age, and fresh syntheses to remedy its defects and fill in its gaps were proposed from different directions.

[97] The physiologist Denis Noble argues that these additions render neo-Darwinism in the sense of the early 20th century's modern synthesis "at the least, incomplete as a theory of evolution",[97] and one that has been falsified by later biological research.

For example, in 2017 Philippe Huneman and Denis M. Walsh stated in their book Challenging the Modern Synthesis that numerous theorists had pointed out that the disciplines of embryological developmental theory, morphology, and ecology had been omitted.

They noted that all such arguments amounted to a continuing desire to replace the modern synthesis with one that united "all biological fields of research related to evolution, adaptation, and diversity in a single theoretical framework.

So notorious did 'the synthesis' become, that few serious historically minded analysts would touch the subject, let alone know where to begin to sort through the interpretive mess left behind by the numerous critics and commentators.