New Imperialism

[3] During this period, between the 1815 Congress of Vienna after the defeat of Napoleonic France and Imperial Germany's victory in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, Great Britain reaped the benefits of being Europe's dominant military and economic power.

[4] [page needed] The erosion of British hegemony after the Franco-Prussian War, in which a coalition of German states led by Prussia soundly defeated the Second French Empire, was occasioned by changes in the European and world economies and in the continental balance of power following the breakdown of the Concert of Europe, established by the Congress of Vienna.

[5] This competition was sharpened by the Long Depression of 1873–1896, a prolonged period of price deflation punctuated by severe business downturns, which put pressure on governments to promote home industry, leading to the widespread abandonment of free trade among Europe's powers (in Germany from 1879 and in France from 1881).

[6][7] The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 sought to destroy the competition between the powers by defining "effective occupation" as the criterion for international recognition of a territory claim, specifically in Africa.

[citation needed] Observing the rise of trade unionism, socialism, and other protest movements during an era of mass society both in Europe and later in North America, elites sought to use imperial jingoism to co-opt the support of part of the industrial working class.

The British also began connecting Indian cities by railroad and telegraph to make travel and communication easier as well as building an irrigation system for increasing agricultural production.

[citation needed] The new administrative arrangement, crowned with Queen Victoria's proclamation as Empress of India in 1876, effectively replaced the rule of a monopolistic enterprise with that of a trained civil service headed by graduates of Britain's top universities.

However, Jan Willem Janssens, the governor of the Dutch East Indies at the time, fought the British before surrendering the colony; he was eventually replaced by Stamford Raffles.

The British were greatly concerned at the prospect of a Russian invasion of the Crown colony of India, though Russia – badly defeated by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War and weakened by internal revolution – could not realistically afford a military conflict against Britain.

Still, the central lesson of the war with Japan was not lost on the Russian General Staff: an Asian country using Western technology and industrial production methods could defeat a great European power.

Meanwhile, new but not exactly modern Chinese armies suppressed the midcentury rebellions, bluffed Russia into a peaceful settlement of disputed frontiers in Central Asia, and defeated the French forces on land in the Sino-French War (1884–1885).

By the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, China was forced to recognize Korea's exit from the Imperial Chinese tributary system, leading to the proclamation of the Korean Empire, and the island of Taiwan was ceded to Japan.

In 1898, Russia obtained access to Dairen and Port Arthur and the right to build a railroad across Manchuria, thereby achieving complete domination over a large portion of northeast China.

The erosion of Chinese sovereignty contributed to a spectacular anti-foreign outbreak in June 1900, when the "Boxers" (properly the society of the "righteous and harmonious fists") attacked foreign legations in Beijing.

German forces were particularly severe in exacting revenge for the killing of their ambassador, while Russia tightened its hold on Manchuria in the northeast until its crushing defeat by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905.

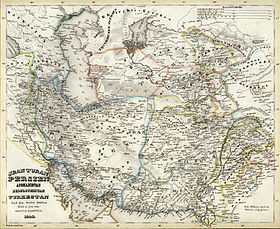

The classic Great Game period is generally regarded as running approximately from the Russo-Persian Treaty of 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, in which nations like Emirate of Bukhara fell.

[39] Britain's formal occupation of Egypt in 1882, triggered by concern over the Suez Canal, contributed to a preoccupation over securing control of the Nile River, leading to the conquest of neighboring Sudan in 1896–1898, which in turn led to confrontation with a French military expedition at Fashoda in September 1898.

In 1899, Britain set out to complete its takeover of the future South Africa, which it had begun in 1814 with the annexation of the Cape Colony, by invading the gold-rich Afrikaner republics of Transvaal and the neighboring Orange Free State.

Paradoxically, the United Kingdom, a staunch advocate of free trade, emerged in 1913 with not only the largest overseas empire, thanks to its long-standing presence in India, but also the greatest gains in the conquest of Africa, reflecting its advantageous position at its inception.

[40] Henry Morton Stanley was employed to explore and colonize the Congo River basin area of equatorial Africa in order to capitalize on the plentiful resources such as ivory, rubber, diamonds, and metals.

[41] Over the next few years, Stanley overpowered and made treaties with over 450 native tribes, acquiring him over 2,340,000 square kilometres (905,000 sq mi) of land, nearly 67 times the size of Belgium.

[52][A] Nonetheless, the first stage of the country's expansionism into the Pacific began only a decade later, in 1851, when—in response to an American incursion into the Juan Fernández Islands—Chile's government formally organized the islands into a subdelegation of Valparaíso.

[54] That same year, Chile's economic interest in the Pacific were renewed after its merchant fleet briefly succeeded in creating an agricultural goods exchange market that connected the Californian port of San Francisco with Australia.

[55] By 1861, Chile had established a lucrative enterprise across the Pacific, its national currency abundantly circulating throughout Polynesia and its merchants trading in the markets of Tahiti, New Zealand, Tasmania, and Shanghai; negotiations were also made with the Spanish Philippines, and altercations reportedly occurred between Chilean and American whalers in the Sea of Japan.

The Fashoda incident of 1898 represented the worst Anglo-French crisis in decades, but France's buckling in the face of British demands foreshadowed improved relations as the two countries set about resolving their overseas claims.

As a result, some modern historical revisionists have suggested that new imperialism was driven more by the idea of racial and cultural supremacism, and that claims of "humanitarianism" were either insincere or used as pretexts for territorial expansion.

In 1901, the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina announced that the Netherlands accepted an ethical responsibility for the welfare of their colonial subjects despite clearly being discriminatory towards the oppressed colonised peoples.

The policy suffered, however, from serious underfunding, inflated expectations and lack of acceptance in the Dutch colonial establishment, and it had largely ceased to exist by the onset of the Great Depression in 1929.

The "World-Systems theory" approach of Immanuel Wallerstein sees imperialism as part of a general, gradual extension of capital investment from the "core" of the industrial countries to a less developed "periphery."

Protectionism and formal empire were the major tools of "semi-peripheral," newly industrialized states, such as Germany, seeking to usurp Britain's position at the "core" of the global capitalist system.