Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province

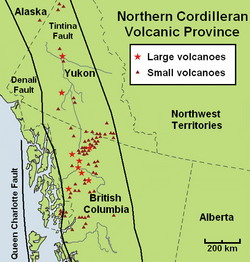

[3] But the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province is recognized to include over 100 independent volcanoes that have been active in the past 1.8 million years.

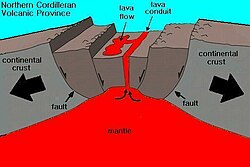

Unlike other parts of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province has its origins in continental rifting—an area where the Earth's crust and lithosphere is being pulled apart.

[6] As these far-field forces stretch the North American crust, the near surface rocks fracture along steeply dipping faults parallel to the rift zone.

Volcanoes within the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province are located along short northerly trending segments which in the northern part of the volcanic province are unmistakenably involved with north-trending rift structures, including synvolcanic grabens and grabens with one major fault line along only one of the boundaries (half-grabens).

Two major north-trending faults hundreds of kilometres long extend along the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province.

[1] A range of more heavily alkaline rock types not commonly found in the Western Cordillera are regionally widespread in the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province.

[1] One hypothesized explanation for oceanic island basalt in the Earth's upper mantle under the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province is the existence of a slab window.

[1] However, more recent mapping and seismic studies in the Coast Mountains have documented the presence of brittle rift-related faults southwest of the small community of Stewart in northwestern British Columbia.

[1] In 1999, a sequence of north-trending faults were mapped that seem to represent young rifting events parallel with the southwestern boundary of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province.

[1] This finally caused the formation of a slab window under the northern portion of the Western Cordillera 10 million years ago, supporting an entrance to relatively undepleted upper mantle.

[1] A switch in relative plate motions at the Queen Charlotte Fault 10 million years ago produced consequent strain throughout the northern portion of the Western Cordillera, resulting in crustal thinning and decompression melting of oceanic island basalt-like mantle to create alkaline volcanism.

[1] Several plate motion models indicate a rebound to net compression throughout the Queen Charlotte Fault sometime after four million years ago.

[3] Felsic magmas from more viscous eruptions create the massive central volcanoes and largely consist of trachyte, pantellerite and comendite lavas.

[3] An area of continental rifting, such as the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province, would aid the formation of high-level reservoirs of capable size and thermal activity to maintain long-lived fractionation.

[7] Analysis of recent data related to earthquakes in the southwestern portion of the volcanic province indicates that the crust under Stikinia, which comprises the bedrock underlying a large number of volcanoes in the southern portion of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province, is also more dense than the crust under the nearby Coast Plutonic Complex, which consists of a broad belt of granitic and dioritic intrusive rocks that collectively represent more than 140 million years of nearly continuous subduction-related magmatism.

In some cases, the heated groundwater may rise along extensional faults related to rifting in the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province.

[1] Granulite xenoliths exist mainly at the Fort Selkirk Volcanic Field in central Yukon, Prindle Volcano in easternmost Alaska and at Castle Rock and the Iskut River in northern British Columbia.

[1] Megacrysts, crystals or grains that are considerably larger than the encircling matrix, are commonly found in lava flows throughout the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province.

[1] Black glassy clinopyroxene megacrysts are widespread throughout the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province, suggesting their creation is independent of lithosphere structure.

[1] Megacrysts made of plagioclase and clinopyroxene regionally show significant evidence of reaction with the associated magma, including sieve-textured cores and random, resorbed and embayed outer margins wherever they are located.

[1] The bedrock of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province consists of four large terranes, known as Stikinia, Cache Creek, Yukon–Tanana and Cassiar.

[1] Stikinia is a sequence of late Paleozoic and Mesozoic aged volcanic, plutonic and sedimentary rocks interpreted to have been created in an island arc environment that were later placed along a pre-existing continental margin.

[1] It comprises late Paleozoic to Mesozoic aged oceanic melange and abyssal peridotites intruded by younger granitic intrusions.

[1] The northern and western boundaries are adjoined by the Yukon–Tanana and Cache Creek terranes where there lies volcanics in eastern Alaska and weathered remains of lava flows just north and west of Dawson City in west-central Yukon.

[1] As a geographic descriptor, application of the name Stikine to volcanic rocks exposed along the Yukon River seems a bit odd and confusing.