Number theory

Number theory is a branch of pure mathematics devoted primarily to the study of the integers and arithmetic functions.

The use of the term arithmetic for number theory regained some ground in the second half of the twentieth century, arguably in part due to French influence.

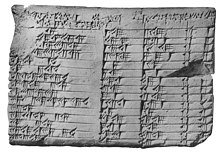

The earliest historical find of an arithmetical nature is a fragment of a table: the broken clay tablet Plimpton 322 (Larsa, Mesopotamia, c. 1800 BC) contains a list of "Pythagorean triples", that is, integers

The heading over the first column reads: "The takiltum of the diagonal which has been subtracted such that the width..."[2] The table's layout suggests[3] that it was constructed by means of what amounts, in modern language, to the identity which is implicit in routine Old Babylonian exercises.

[13] By revealing (in modern terms) that numbers could be irrational, this discovery seems to have provoked the first foundational crisis in mathematical history; its proof or its divulgation are sometimes credited to Hippasus, who was expelled or split from the Pythagorean sect.

The result was later generalized with a complete solution called Da-yan-shu (大衍術) in Qin Jiushao's 1247 Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections [18] which was translated into English in early nineteenth century by British missionary Alexander Wylie.

Eusebius, PE X, chapter 4 mentions of Pythagoras: "In fact the said Pythagoras, while busily studying the wisdom of each nation, visited Babylon, and Egypt, and all Persia, being instructed by the Magi and the priests: and in addition to these he is related to have studied under the Brahmans (these are Indian philosophers); and from some he gathered astrology, from others geometry, and arithmetic and music from others, and different things from different nations, and only from the wise men of Greece did he get nothing, wedded as they were to a poverty and dearth of wisdom: so on the contrary he himself became the author of instruction to the Greeks in the learning which he had procured from abroad.

Theaetetus was, like Plato, a disciple of Theodorus's; he worked on distinguishing different kinds of incommensurables, and was thus arguably a pioneer in the study of number systems.

The Arithmetica is a collection of worked-out problems where the task is invariably to find rational solutions to a system of polynomial equations, usually of the form

could be solved by a method he called kuṭṭaka, or pulveriser;[29] this is a procedure close to (a generalisation of) the Euclidean algorithm, which was probably discovered independently in India.

[31] Indian mathematics remained largely unknown in Europe until the late eighteenth century;[32] Brahmagupta and Bhāskara's work was translated into English in 1817 by Henry Colebrooke.

Other than a treatise on squares in arithmetic progression by Fibonacci—who traveled and studied in north Africa and Constantinople—no number theory to speak of was done in western Europe during the Middle Ages.

[37] Pierre de Fermat (1607–1665) never published his writings; in particular, his work on number theory is contained almost entirely in letters to mathematicians and in private marginal notes.

[50][51] This has been called the "rebirth" of modern number theory,[52] after Fermat's relative lack of success in getting his contemporaries' attention for the subject.

[53] Euler's work on number theory includes the following:[54] Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813) was the first to give full proofs of some of Fermat's and Euler's work and observations—for instance, the four-square theorem and the basic theory of the misnamed "Pell's equation" (for which an algorithmic solution was found by Fermat and his contemporaries, and also by Jayadeva and Bhaskara II before them.)

A conventional starting point for analytic number theory is Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions (1837),[72][73] whose proof introduced L-functions and involved some asymptotic analysis and a limiting process on a real variable.

[74] The first use of analytic ideas in number theory actually goes back to Euler (1730s),[75][76] who used formal power series and non-rigorous (or implicit) limiting arguments.

For example, the prime number theorem was first proven using complex analysis in 1896, but an elementary proof was found only in 1949 by Erdős and Selberg.

For that matter, the eleventh-century chakravala method amounts—in modern terms—to an algorithm for finding the units of a real quadratic number field.

Their classification was the object of the programme of class field theory, which was initiated in the late nineteenth century (partly by Kronecker and Eisenstein) and carried out largely in 1900–1950.

For example, as explained below, algorithms in number theory have a long history, arguably predating the formal concept of proof.

must happen sometimes; one may say with equal justice that many applications of probabilistic number theory hinge on the fact that whatever is unusual must be rare.

At times, a non-rigorous, probabilistic approach leads to a number of heuristic algorithms and open problems, notably Cramér's conjecture.

In its basic form (namely, as an algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor) it appears as Proposition 2 of Book VII in Elements, together with a proof of correctness.

, or, what is the same, for finding the quantities whose existence is assured by the Chinese remainder theorem) it first appears in the works of Āryabhaṭa (fifth to sixth centuries) as an algorithm called kuṭṭaka ("pulveriser"), without a proof of correctness.

The difficulty of a computation can be useful: modern protocols for encrypting messages (for example, RSA) depend on functions that are known to all, but whose inverses are known only to a chosen few, and would take one too long a time to figure out on one's own.

[88] In 1974, Donald Knuth said "virtually every theorem in elementary number theory arises in a natural, motivated way in connection with the problem of making computers do high-speed numerical calculations".

The first can be answered most satisfactorily by reciprocal pairs, as first suggested half a century ago, and the second by some sort of right-triangle problems (Robson 2001, p. 202).Robson takes issue with the notion that the scribe who produced Plimpton 322 (who had to "work for a living", and would not have belonged to a "leisured middle class") could have been motivated by his own "idle curiosity" in the absence of a "market for new mathematics".

From the remainder take away 1 representing the heaven, 2 the earth, 3 the man, 4 the four seasons, 5 the five phases, 6 the six pitch-pipes, 7 the seven stars [of the Dipper], 8 the eight winds, and 9 the nine divisions [of China under Yu the Great].

Two of the most popular introductions to the subject are: Hardy and Wright's book is a comprehensive classic, though its clarity sometimes suffers due to the authors' insistence on elementary methods (Apostol 1981).