Ore Mountains

The higher altitudes from around 500 m above sea level on the German side belong to the Ore Mountains/Vogtland Nature Park – the largest of its kind in Germany with a length of 120 km.

The Ore Mountains are a Hercynian block tilted so as to present a steep scarp face towards Bohemia and a gentle slope on the German side.

By the end of the Palaeozoic era, the mountains had been eroded into gently undulating hills (the Permian massif), exposing the hard rocks.

This can be very clearly seen at a height of 807 m above sea level (NN) on the mountain of Komáří vížka which lies on the Czech side, east of Zinnwald-Georgenfeld, right on the edge of the fault block.

[4] The most important rocks occurring in the Ore Mountains are schist, phyllite and granite with contact metamorphic zones in the west, basalt as remnants in the Plešivec (Pleßberg), Scheibenberg, Bärenstein, Pöhlberg, Velký Špičák (Großer Spitzberg or Schmiedeberger Spitzberg), Jelení hora (Haßberg) and Geisingberg as well as gneisses and rhyolite (Kahleberg) in the east.

As a result of the subsoils based on granite and rhyolite, the land is mostly covered in forest; on the gneiss soils it was possible to grow and cultivate flax in earlier centuries and, later, rye, oats and potatoes up to the highlands.

The Eastern Ore Mountains mainly comprise large, gently climbing plateaux, in contrast with the steeper and higher-lying western and central areas, and are dissected by river valleys that frequently change direction.

Geologically the Ore Mountains reach the city limits of Dresden at the Windberg hill near Freital and the Karsdorf Fault.

From this perspective, its main characteristics, i.e., gently sloping plateaus climbing up to the ridgeline incised by V-shaped valleys, continue to the southern edge of the Dresden Basin.

Temperatures are considerably lower all year round than in the lowlands, and the summer is noticeably shorter and cool days are frequent.

Historic sources describe hard winters in which cattle froze to death in their stables, and occasionally houses and cellars were snowed in even after snowfalls in April.

As a result of the climate and the heavy amounts of snow a natural Dwarf Mountain Pine region is found near Satzung, near the border to Bohemia at just under 900 m above sea level (NN).

[13][14] By the Medieval period, Iberia's and Germany's deposits lost importance and were largely forgotten while Devon and Cornwall began dominating the European tin market.

[12] From the time of the first wave of settlement, the history of the Ore Mountains has been heavily influenced by its economic development, especially that of the mining industry.

The emergence of this branch of trade benefited from the abundance of excess timber, which was created by clearings and new settlements and which was able to meet the high demand of the glassworks.

An indication of this is a contract between Boresch of Riesenburg and the Ossegg abbot, Gerwig, in which the division of revenue derived from ore was agreed.

Under Emperor Ferdinand II an unprecedented Re-Catholicization began in Bohemia from 1624 to 1626, whereupon a large number of Bohemian Protestants then fled into the neighbouring Electorate of Saxony.

As a result, many Bohemian villages became devastated and desolate, while on the Saxon side new places were founded by these migrants, such as the mining town of Johanngeorgenstadt.

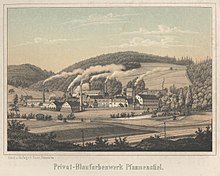

Due to the very sharp decline of the mining industry and because the search for new ore deposits proved fruitless, the population had to resort to other occupations.

They succeeded in keeping the method of production secret for a long time, so that for about 100 years the blue colour works had a worldwide monopoly.

Drainage costs increased, from the mid-19th century, led to a steady decrease in yield, despite sinking of deeper galleries (Erbstollen) and the expansion of ditch and tunnel (Rösche) systems for supplying the necessary water for overshot wheels from the crest of the mountains, such as the Freiberg Mines Water Management System or the Reitzenhainer Zeuggraben.

But even the excavation of the Rothschönberger Stolln, the largest and most important Saxon drainage adit, which drained the entire Freiberg district, could not stop the decline of mining.

The mountains that until the late 11th (and early 12th century) were covered in dense forests were almost completely transformed into a cultural landscape by the mining industry and by settlement.

Mining including the construction of dumps, impoundments, and ditches in many places also directly shaped the scenery and the habitats of plants and animals.

Human interventions have created a unique cultural landscape with a large number of typical biotopes which are worthy of protection such as mountain meadows and wetlands.

Mining, the essential historical basis of industrial development in the Ore Mountains, currently plays only a minor economic role on the Saxon side of the border.

Europe's largest deposits of lithium-bearing mica zinnwaldite in Cínovec, a Czech village between town of Dubí and the border with Germany which gave its old German name Zinnwald to the mineral, are expected to be mined starting 2019 (as of June 2017).

At the beginning of the 20th century, Hans Soph, Stephan Dietrich and especially Anton Günther were active; their works have a lasting impact to this day in Ore Mountain songs and writings.

The most famous include the Preßnitzer Musikanten, Geschwister Caldarelli, Zschorlauer Nachtigallen, the Erzgebirgsensemble Aue and Joachim Süß and his Ensemble.

In addition, traditional Christmas mining celebrations such as the Mettenschicht and Hutzenabende draw many visitors and have made the Ore Mountains known as "Christmasland" (Weihnachtsland).