Ottoman architecture

This style was a mixture of native Turkish tradition and influences from the Hagia Sophia, resulting in monumental mosque buildings focused around a high central dome with a varying number of semi-domes.

[21] One of the early Ottoman stylistic distinctions that emerged was a tradition of designing more complete façades in front of mosques, especially in the form of a portico with arches and columns.

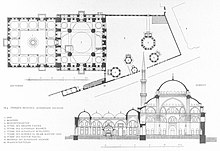

[33] These mosques were all part of larger religious complexes (külliyes) that included other structures offering services such as madrasas (Islamic colleges), hammams (public bathhouses), and imarets (charitable kitchens).

It consists of a large hypostyle hall divided into twenty equal bays in a rectangular four-by-five grid, each covered by a dome supported by stone piers.

[7] The long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent is also recognized as the apogee of Ottoman political and cultural development, with extensive patronage in art and architecture by the sultan, his family, and his high-ranking officials.

He instead experimented with other designs that seemed to aim for a completely unified interior space and for ways to emphasize the visitor's perception of the main dome upon entering a mosque.

Following the example of the earlier Fatih complex, it consists of many buildings arranged around the main mosque in the center, on a planned site occupying the summit of a hill in Istanbul.

[84] Nonetheless, Sinan employed innovations similar to those he used previously in the Şehzade Mosque: he concentrated the load-bearing supports into a limited number of columns and pillars, which allowed for more windows in the walls and minimized the physical separations within the interior of the prayer hall.

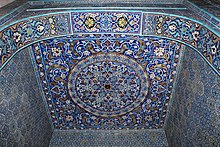

[88] This mosque is also famous for its wide array of Iznik tiles covering the walls of its exterior portico and its interior, unprecedented in Ottoman architecture,[89] contrasting with the usually restrained decoration Sinan employed in other buildings.

This overall design probably emulated French pleasure palaces as a result of the reports about Paris and Versailles brought back by Ottoman ambassador Yirmisekiz Çelebi Mehmed Efendi.

[139] The most important monument heralding the new Ottoman Baroque style is the Nuruosmaniye Mosque complex, begun by Mahmud I in October 1748 and completed by his successor, Osman III (to whom it is dedicated), in December 1755.

[145] In Topkapı Palace, the Ottoman sultans and their family continued to build new rooms or remodel old ones throughout the 18th century, introducing Baroque and Rococo decoration in the process.

[152][153] In eastern Anatolia, near present-day Doğubayazıt, the Ishak Pasha Palace is an exceptional and flamboyant piece of architecture that mixes various local traditions including Seljuk Turkish, Armenian, and Georgian.

[171][172] The Tanzimat reforms also granted Christians and Jews the right to freely build new centers of worship, which resulted in new constructions, renovations, and expansions of churches and synagogues.

[189] New government-run institutions that trained architects and engineers, established in the late 19th century and further centralized under the Young Turks, became instrumental in disseminating this "national style".

[191][192] Especially after Sinan, the design of monumental Ottoman buildings was conceptualized with the central dome above as its starting point, rather than the floor plan being conceived first and the roofing system after.

[203] Ottoman domes were not raised on prominent drums, unlike their Byzantine predecessors,[199] but their outer edge usually rested on a circle of alternating buttresses and windows.

[210][211] The same kind of tilework is found in the mihrab of the Murad II Mosque in Edirne, completed in 1435, along with the first examples of a new technique with underglaze blue on a white background, with touches of turquoise.

[214][215] In the late 15th century, in the 1470s or 1480s, the ceramic industry in the city of İznik was growing and began producing a new "blue-and-white" fritware which adapted and incorporated Chinese motifs in its decoration.

[218][219] They exemplify the advent of the saz style: a motif in which a variety of flowers are attached to gracefully curving stems with serrated leaves, appearing in the 16th century.

The design of the ornamentation was often stenciled onto the plaster first, using paper pierced with pin holes in the shape of the motifs, over which coal dust was rubbed to leave outlines on the walls that were then painted.

[237] Another floriate style that appeared in Ottoman decoration from the 15th century onward is hatayî, which consists in large part of peonies and leaves shown in varying stages of budding and blooming.

The ornamentation inside the southeastern (qibla) iwan depicts natural landscapes with stylized flowers and trees that appear to reflect the same artistic styles used in book illustrations and miniatures, particularly those from the Timurid Empire further east.

[117] The reign of Ahmet III (r. 1703–1730), which include the years of the Tulip Period (1718–1730), saw the popularization of a style derived from this, featuring plentiful depictions of flowers in vases and bowls of fruit, sometimes with shading.

Nonetheless, high-quality stone carving was still used to enrich the details of buildings throughout the Ottoman period, particularly for entrance portals, minaret balconies, niches, column capitals, and moldings.

[134] Although many novelties were introduced, one traditional feature that continued throughout this period were the calligraphic inscriptions placed in panels over gates, in friezes, and in other prominent locations.

At the Fatih Mosque, the courtyard once contained four cypress trees planted around a central fountain, a composition likely originating from the now-vanished atrium of the Hagia Sophia, which featured the same arrangement.

[19] In the Balkans, the reign of Murad II (r. 1421–1451 with brief interruption) saw many renovations of early Ottoman buildings and also the construction of multiple new mosques and civic or religious complexes.

[272] As in many other provincial areas of the empire, mosques in the Balkans generally consisted of the single-dome type with one minaret, though some were also built with sloped wooden roofs instead.

[275][276] The regions along the edges of Anatolia, Syria, and Mesopotamia (around southeastern Turkey today) also resisted assimilation to the culture of the Ottoman capital and continued to be strongly influenced by local styles.