History of Palestine

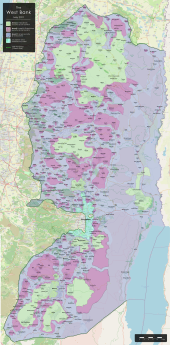

In 1993, the Oslo Peace Accords between Israel and the PLO established the Palestinian Authority (PA), an interim body to run Gaza and the West Bank (but not East Jerusalem), pending a permanent solution.

During the last two hundred years of that period and following the Unification of Egypt and pharaoh Narmer, an Egyptian colony appeared in the southern Levantine coast, with its center at Tell es-Sakan (modern-day Gaza Strip).

[24] In the first year of his reign, the pharaoh Seti I (c. 1294–1290 BCE) waged a campaign to resubordinate Canaan to Egyptian rule, thrusting north as far as Beit She'an, and installing local vassals to administer the area in his name.

The Egyptian Stelae in the Levant, most notably the Beisan steles, and a burial site yielding a scarab bearing the name Seti found within a Canaanite coffin excavated in the Jezreel Valley, attests to Egypt's presence in the area.

[124][125] The Maccabean Revolt, led by Judas Maccabeus,[xlv] highlighted the growing unrest and resistance against Seleucid authority,[124] eventually leading to significant shifts in power dynamics within the region.

[219] Products manufactured or traded in Palestine included building materials from marble and white-stone quarries, spices, soaps, olive oil, sugar, indigo, Dead Sea salts, and silk.

[233] The Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705) and his son al-Walid I (r. 705–715) built two important Islamic religious buildings on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem; the al-Jami'a al-Aqsa[234][lxxxiv] and the Dome of the Rock.

[241][242][243][244][lxxxv] Al-Walid's successor, Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 715–717), ruled from Palestine, where he had long been governor and founded the city of Ramla, which remained the region's administrative center until the Crusader conquest in 1099.

Their arrival marked the beginning of six decades of almost uninterrupted and highly destructive warfare in Palestine between them and their many enemies, the Byzantines, the Qarmatians, Bedouin tribes, and even infighting between Berber and Turkic factions within the Fatimid army.

[citation needed] The Mamluks, continuing the policy of the Ayyubids, made the strategic decision to destroy the coastal area and to bring desolation to many of its cities, from Tyre in the north to Gaza in the south.

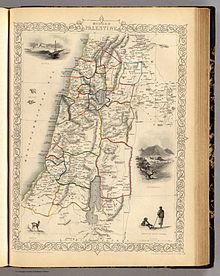

Greater Syria became an eyalet (province) ruled from Damascus, while the Palestine region within it was divided into the five sanjaks (provincial districts, also called liwa′ in Arabic) of Safad, Nablus, Jerusalem, Lajjun and Gaza.

[319] For much of the 16th century, the Ottomans ruled Damascus Eyalet in a centralised way, with the Istanbul-based Sublime Porte (imperial government) playing a crucial role in maintaining public order and domestic security, collecting taxes, and regulating the economy, religious affairs and social welfare.

[332] In 1622, the Druze emir (prince) of Mount Lebanon, Fakhr-al-Din II gained control of Safad Sanjak and was appointed governor of Nablus and mutasallim (chief tax collector) of Gaza.

[331] Alarmed at the looming threat to their rule, the Ridwan-Farrukh-Turabay alliance prepared for a confrontation with Fakhr ad-Din by pooling their financial resources to acquire arms and bribe Bedouin tribes to fight alongside them.

[337] In 1657, the Ottoman authorities launched a military expedition in Palestine to reassert imperial control over the region because of its strategic importance in the funding and protection of the Hajj caravan and also because it was a crucial link to Egypt.

[343] In reaction to this state of affairs, in 1703, an uprising, known as the Naqib al-Ashraf Revolt, by the people of Jerusalem took place, led by the chief of the ashraf families, Muhammad ibn Mustafa al-Husayni, and backed by the city's notables.

[343] Meanwhile, the mostly Arab sipahi officers of the 1657 centralization expedition, chief among them members of the Nimr family, settled in Nablus and, contrary to the Sublime Porte's intention, began forming their own local power bases in the city's rural hinterland from the timars they were assigned.

[380] He also made significant cuts to Acre's military and adopted a decentralization policy of non-interference with his deputy governors, such as Muhammad Abu-Nabbut of Jaffa, and diplomacy with various autonomous sheikhs, such as Musa Bey Tuqan of Nablus.

The core of the rebels were based in Jabal Nablus and led by subdistrict chief Qasim al-Ahmad,[403] who had previously contributed peasant irregulars to Ibrahim Pasha's forces during the conquest of Syria.

"[411] In common usage from 1840 onward, "Palestine" was used either to describe the consular jurisdictions of the Western powers[412] or for a region that extended in the north–south direction typically from Rafah (south-east of Gaza) to the Litani River (now in Lebanon).

The Zionist Organization's representative at Sanremo, Chaim Weizmann, subsequently reported to his colleagues in London:There are still important details outstanding, such as the actual terms of the mandate and the question of the boundaries in Palestine.

[439]In July 1920, the French drove Faisal bin Husayn from Damascus, ending his already negligible control over the region of Transjordan, where local chiefs traditionally resisted any central authority.

The border was re-drawn so that both sides of the Jordan River and the whole of the Sea of Galilee, including a 10-metre-wide strip along the northeastern shore, were made a part of Palestine,[444] with the provisions that Syria have fishing and navigation rights in the lake.

[445] The first reference to the Palestinians, without qualifying them as Arabs, is to be found in a document of the Permanent Executive Committee, composed of Muslims and Christians, presenting a series of formal complaints to the British authorities on 26 July 1928.

In a meeting in Alexandria in July 1937 between Irgun founder Ze'ev Jabotinsky, commander Col. Robert Bitker and chief-of-staff Moshe Rosenberg, the need for indiscriminate retaliation due to the difficulty of limiting operations to only the "guilty" was explained.

This was caused by a combination of factors, including: In early 1947 the British Government announced their desire to terminate the Mandate, and asked the United Nations General Assembly to make recommendations regarding the future of the country.

[488] On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly, voting 33 to 13 in favour with 10 abstentions, adopted Resolution 181 (II) (though not legally binding)[489] recommending a partition with the Economic Union of Mandatory Palestine to follow the termination of the British Mandate.

The New Historians, like Avi Shlaim, hold that there was an unwritten secret agreement between King Abdullah of Transjordan and Israeli authorities to partition the territory between themselves, and that this translated into each side limiting their objectives and exercising mutual restraint during the 1948 war.

[504] The presence of a large number of immigrants and refugees from the now dissolved Mandate of Palestine fueled the regional ambitions of King Abdullah I, who sought control over what had been the British Jerusalem and Samaria districts on the West Bank of the Jordan River.

[505] In the course of the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel captured the rest of the area that had been part of the British Mandate of Palestine, taking the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt.