Hypoxia (environmental)

An aquatic system lacking dissolved oxygen (0% saturation) is termed anaerobic, reducing, or anoxic.

Most fish cannot live below 30% saturation since they rely on oxygen to derive energy from their nutrients.

During summer stratification, inputs or organic matter and sedimentation of primary producers can increase rates of respiration in the hypolimnion.

If oxygen depletion becomes extreme, aerobic organisms, like fish, may die, resulting in what is known as a "summer kill".

During winter, ice and snow cover can attenuate light, and therefore reduce rates of photosynthesis.

When the oxygen becomes badly depleted, anaerobic organisms can die, resulting in a "winter kill".

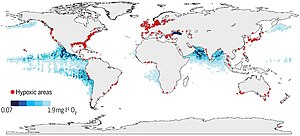

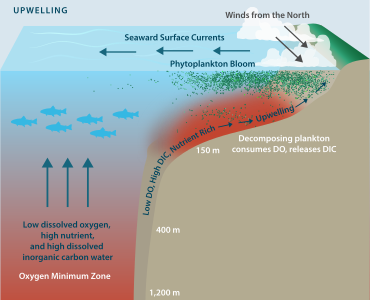

[8] Oxygen depletion can result from a number of natural factors, but is most often a concern as a consequence of pollution and eutrophication in which plant nutrients enter a river, lake, or ocean, and phytoplankton blooms are encouraged.

When phytoplankton cells die, they sink towards the bottom and are decomposed by bacteria, a process that further reduces DO in the water column.

Low dissolved oxygen conditions are often seasonal, as is the case in Hood Canal and areas of Puget Sound, in Washington State.

[10] Hypoxia may also be the explanation for periodic phenomena such as the Mobile Bay jubilee, where aquatic life suddenly rushes to the shallows, perhaps trying to escape oxygen-depleted water.

Recent widespread shellfish kills near the coasts of Oregon and Washington are also blamed on cyclic dead zone ecology.

[11] Phytoplankton are mostly made up of lignin and cellulose, which are broken down by oxidative mechanism, which consume oxygen.

[17] As phytoplankton breakdown, free phosphorus and nitrogen become available in the environment, which also fosters hypoxic conditions.

As more minerals such as phosphorus and nitrogen are displaced into these aquatic systems, the growth of phytoplankton greatly increases, and after their death, hypoxic zones are formed.