Ozone–oxygen cycle

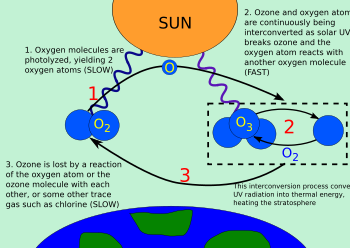

The ozone–oxygen cycle is the process by which ozone is continually regenerated in Earth's stratosphere, converting ultraviolet radiation (UV) into heat.

[1] The Chapman cycle describes the main reactions that naturally determine, to first approximation, the concentration of ozone in the stratosphere.

While keeping the ozone layer in stable balance, and protecting the lower atmosphere from harmful UV radiation, the cycle also provides one of two major heat sources in the stratosphere (the other being kinetic energy, released when O2 is photolyzed into individual O atoms).

The overall amount of ozone in the stratosphere is determined by the balance between production from solar radiation and its removal.

Most OH and NO are naturally present in the stratosphere, but human activity - especially emissions of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and halons - has greatly increased the concentration of Cl and Br, leading to ozone depletion.

Each Cl or Br atom can catalyze tens of thousands of decomposition reactions before it is removed from the stratosphere.

Thus, when both reactions are balanced, the ratio between ozone and molecular oxygen concentrations is approximately proportional to air density.

With ozone concentrations in the order of 10−6-10−5 relative to molecular oxygen, ozone photodissociation becomes the dominant photodissociation reaction, and most of the stratosphere heat is generated through this procsees, with highest heat generation rate per molecule at the upper limit of the stratosphere (stratopause), where ozone concentration is already relatively high while UV flux is still high as well in those wavelengths, before being depleted by this same photodissociation process.

Rather, tropospheric ozone chemistry is dominated today by industrial pollutants other gases of volcanic source.